Echodataflow: Recipe-based Fisheries Acoustics Workflow Orchestration

Abstract¶

With the influx of large data from multiple instruments and experiments, scientists are wrangling complex data pipelines that are context-dependent and non-reproducible. We demonstrate how we leverage Prefect Prefect, 2024, a modern orchestration framework, to facilitate fisheries acoustics data processing. We built a Python package Echodataflow Echodataflow, 2024 which 1) allows users to specify workflows and their parameters through editing text “recipes” which provide transparency and reproducibility of the pipelines; 2) supports scaling of the workflows while abstracting the computational infrastructure; 3) provides monitoring and logging of the workflow progress. Under the hood, Echodataflow uses Prefect to execute the workflows while providing a domain-friendly interface to facilitate diverse fisheries acoustics use cases. We demonstrate the features through a typical ship survey data processing pipeline.

1Motivation¶

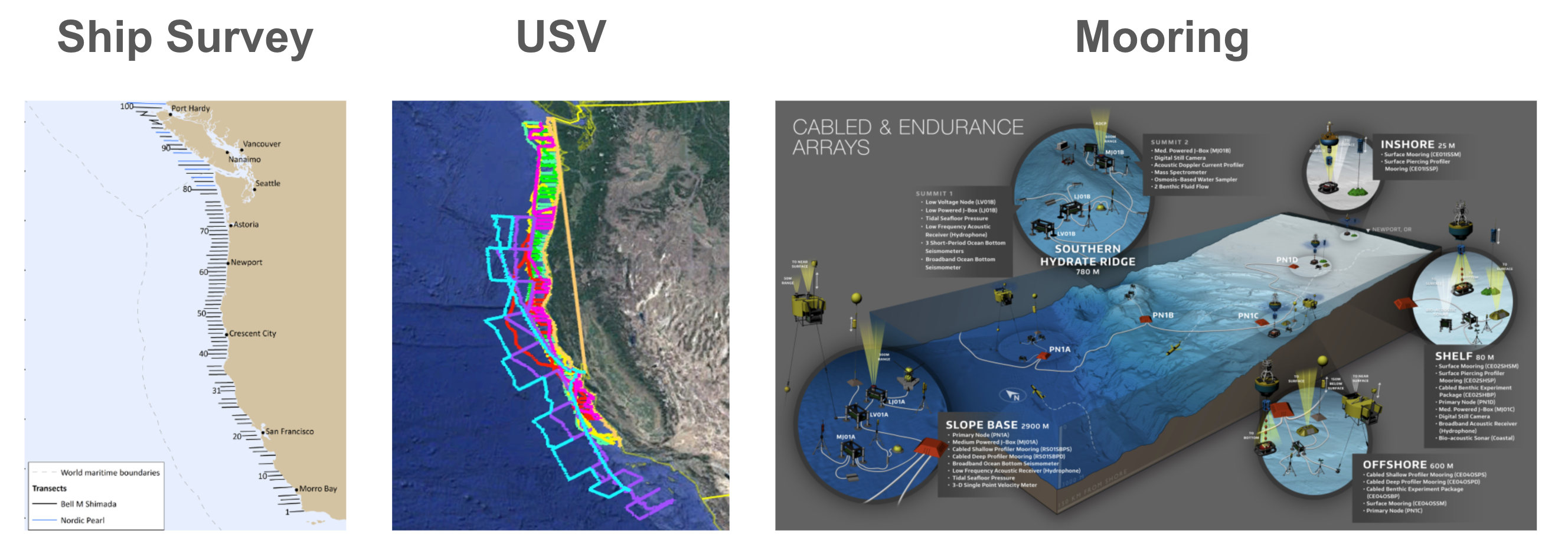

Acoustic fisheries surveys and ocean observing systems collect terabytes of echosounder (water column sonar) data that require custom processing pipelines to obtain the distributions and abundance of fish and zooplankton in the ocean NOAA National Center for Environmental Information, 2024. The data are collected by sending an acoustic signal into the ocean which scatters from objects in the water column and the returning “echo” is recorded. Although data usually have similar dimensions: range, time, location, and frequency, and can be stored into multi-dimensional arrays, the exact format varies based on the data collection scheme and the exact instrument used. Fisheries ship surveys, for example, follow pre-defined paths (transects) and can span several months (Figure 1 left). Ocean moorings, on the other hand, have instruments at fixed locations and can collect data continuously at specified intervals for months (Figure 1 right). Uncrewed Surface Vessels (USVs) (e.g. Saildrone Saildrone, 2024, DriX DriX, 2024, Figure 1 middle) can autonomously collect echosounder data over large spatial regions. In all these scenarios, data are usually collected with similar instruments, and there is an overlap between the initial processing procedures. However, there are always variations associated with the specific data collection format, end research needs, data volume, and available computational infrastructure. For example, ship surveys may require grouping data along individual transects and exluding other data; they may also have varying range/depth resulting into data arrays of different dimensions. Mooring data are more regular, but their volume is large, and studies may require organizing data into daily patterns to analyze long term trends. USVs collect data at varying speeds thus requiring converting the time dimension to distance in order to have consistent echo patterns. The time when the data needs to be processed also affects the workflows: on premise/realtime applications usually require processing small data subsets at a time with limited computing resources; historical analyses require processing large datasets, and can benefit from cluster/cloud computing. The various scenarios demand different data workflows, and adapting from one setting to another is not trivial.

Figure 1:Data Collection Schemes: left, ship survey transect map for the Joint U.S.-Canada Integrated Ecosystem and Pacific Hake Acoustic Trawl Survey Northwest Fisheries Science Center, Fishery Resource Analysis and Monitoring Division, 2022; middle, USV path map for Saildrone west coast survey Saildrone, 2019; right, map and instrument diagram for a stationary ocean observing system (Ocean Observatories Initiative Cabled and Endurance Arrays Trowbridge et al., 2019, Image Credit: Center for Environmental Visualization, University of Washington)

2Fisheries Acoustics Workflows¶

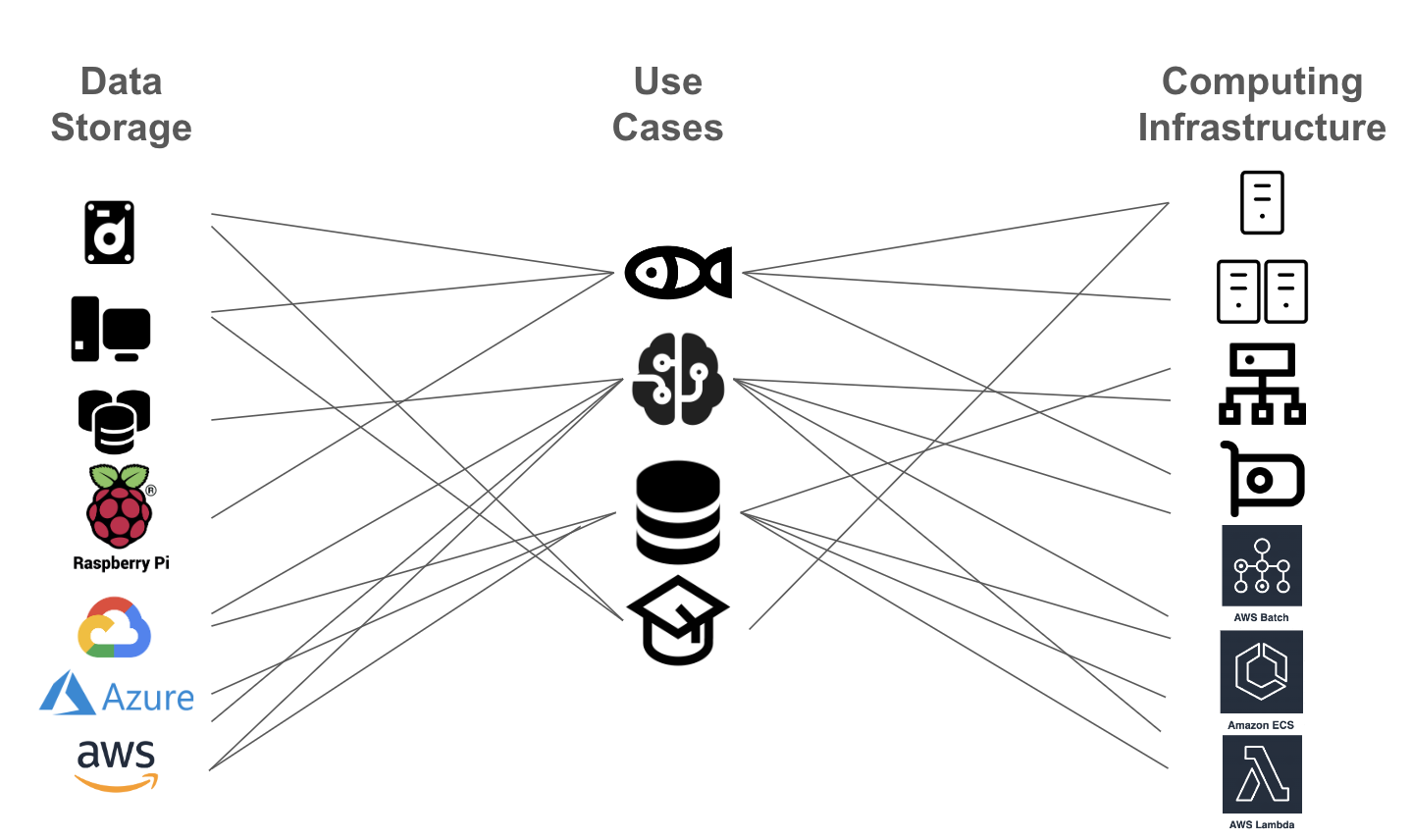

Fisheries acoustics scientists traditionally have had go-to tools and procedures for their data processing and analysis, mostly relying on computation on a local computer. However, as the diversity of computing and data storage resources grows and the field becomes more interdisciplinary (it involves scientists with backgrounds in physics, biology, oceanography, acoustics, signal processing, machine learning, software engineering, etc.), it is becoming more challenging to make decisions on the best arrangement to accomplish the work. For example, Figure 2 shows the many variations of workflows that can be defined based on the use cases and the options for data storage and computing infrastructure.

Figure 2:Fisheries Acoustics Workflow Variations: Various use cases (fisheries, data management, machine learning, education) drive different needs for data storage and computing infrastructure. Options are abundant but adopting new technology and adapting workflows across use cases is not trivial.

2.1User Stories¶

To demonstrate the software requirements of the fisheries acoustics community, below we describe several example user stories.

A fisheries scientist needs to process all data after a 2-month ship survey to obtain fish biomass estimates. They have previously used a commercial software package and are open to exploring open-source tools to achieve the same goal. They are familiar with basic scripting in Python.

A machine learning engineer is developing an ML algorithm to automatically detect fish on a USV. They need to prepare a large dataset for training but do not know all the necessary preprocessing steps. They are very familiar with ML libraries but do not have the domain-specific knowledge for acoustic data processing. They are also not familiar with distributed computing libraries.

A data manager wants to process several terabytes of mooring data and serve them to the scientific community. They have a few Python scripts to do this for a small set of files at a time, but want to scale the processing for many deployments using a cloud infrastructure.

An acoustics graduate student obtained echosounder data analysis scripts from a retired scientist but does not have all the parameters needed to reproduce the results in order to proceed with their dissertation research.

We draw attention to the different levels of experience of these users: each user has expertise in a subdomain, however, to accomplish their specific goal(s), they need to learn new tools or obtain knowledge from others. We outline several requirements that stem from these stories:

- The system should run both on a local computer and within a cloud environment.

- The system should allow processing to be scaled to large datasets, but should not be overly complicated. For example, users with Python scripting experience can run it locally with pre-defined stages and parameters.

- The system should provide visibility into the operations that are applied to the data, and the procedures should be interpretable to users without acoustics expertise.

- The system should preferably be free and open source so that it is accessible to members of different institutions.

- The system should adapt to rapid changes of cloud and distributed computing libraries, and preferably should leverage existing developments within the technical communities.

2.2Software Landscape¶

Traditionally echosounder data processing pipelines are executed within a GUI-based software (e.g. Echoview Echoview Software Pty Ltd, 2020, LSSS Korneliussen et al., 2006, ESP3 Ladroit et al., 2020, Matecho Perrot et al., 2018). These software packages have been invaluable for onboard real-time visualization, as well as post-survey data screening and annotation. Some of them also support integration with scripting tools which facilitates the reproducible execution of the pipelines. For example, the Echoview software provides the option to automate pipelines through an Automation Module and to visualize the processing stages in a Dataflow Toolbox. Further, one can script operations through the echoviewR package Harrison et al., 2015. However, since Echoview is neither free nor open source, these pipelines cannot be shared with researchers who do not have a license. In general, the GUI tools are usually designed to be used on a desktop computer and require downloading the data first, which is becoming challenging with the growing volume of the datasets. There has been also growth in development of new methods to detect the species of interest from the echosounder data, with the goal of substituting for the manual annotation procedures and making analysis of large datasets more efficient and objective. However, the new methods are typically developed independently from the existing software packages.

Over the last several years there has been substantial development of open source Python packages (PyEchoLab Wall et al., 2018, echopype Lee et al., 2021, echopy open-ocean-sounding/echopy, 2024), each providing common echosounder processing functionalities, but differing in the data structure organization and processing. Since echosounder instruments store the data in binary, instrument-specific formats, the first stage requires parsing the raw data into a more common format. PyEcholab converts the data into numpy Harris et al., 2020 arrays. echopy expects data are already parsed into numpy arrays and all methods operate on them. Echopype converts raw data files into a standardized Python EchoData object, which can be stored in a zarr Miles et al., 2024 format and supports distributed computing by utilizing dask Dask Development Team, 2016 and xarray Hoyer & Hamman, 2017. The use of open source packages and well-established formats allow further integration with other open source libraries such as those for machine learning (e.g. classification, clustering) or visualization. In addition, if custom modification is required for a specific application scenario, researchers can adapt the code and contribute the modification back to the packages, which is likely to benefit other researchers.

2.2.1Challenges¶

Despite the availability of methods and tools to process echosounder data, it is not trivial to orchestrate all function calls in an end-to-end pipeline. While a well-documented Jupyter Kluyver et al., 2016 notebook can show the sequence of processing stages, a considerable amount of path and parameter configuration is required to execute these stages on a large dataset, store the intermediate data products, and log the process comprehensively. Although automation can be achieved through a combination of Python and bash scripts that provision the environment, execute the stages, and manage inputs/outputs, the configuration process can be tedious, prone to error, and specific to the use case and the computing platform. Adapting an existing procedure to a new setting is usually not straightforward, and sometimes even reproducing previous results can pose a challenge. Below we discuss in more detail the different choices of data storage and computational infrastructure and the associated challenges of building workflows across them.

2.2.1.1Data Storage¶

Researchers are faced with decisions of where to store the data from experiments, intermediate products, and final results. Initially, data are usually stored on local hard drive storage associated with the instrument (which on some platforms may have limited capacity), but eventually, these data may be transferred to a data archive if one is maintained within the community. Some agencies (e.g. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) Wall, 2016) have adopted cloud storage, and have publicly shared their data, which greatly facilitates data access and reuse. However, those repositories are usually not where researchers can store processed products. Funding models and organizational structure can result in short-term availability of resources and the need to change providers. Certain applications may need to access the data before they are archived and unreliable internet connection may require storing the data on-premise or at temporary locations. To be agile to those frequent changes and allow to easily switch between different platforms, workflows will benefit from a level of abstraction from storage systems.

2.2.1.2Computing Infrastructure¶

With the growth of the echosounder datasets, researchers face challenges processing the data on their personal machines: both in terms of memory usage and computational time. A typical first attempt for resolution would be to amend the workflow to process smaller chunks of the data and parallelize operations across multiple cores if available. However, today researchers are also presented with a multitude of options for distributed computing: high-performance computing clusters at local or national institutions, cloud provider services: batch computing (e.g. Azure Batch, AWS Batch, Google Cloud Batch), container services (e.g. Amazon Elastic Container Services, Azure Container Apps, Google Kubernetes Engine), serverless functions (e.g. AWS Lamdba Functions, Google Cloud Functions, Microsoft Azure Functions). The choice may be driven by the storage system: its usage fees and retrieval speeds. Data, code and workflow organization usually has to be adapted based on the computing infrastructure. The knowledge required to configure these systems to achieve efficient processing is quite in-depth, and distributed libraries can be hard to debug and can have unexpected performance bottlenecks. Abstracting the computing infrastructure and the execution of the tasks can allow researchers to focus on the scientific analysis of these large and rich datasets.

3Echodataflow Overview¶

At the center of echodataflow’s design Echodataflow, 2024 is the notion that a workflow can be configured through a set of recipes (.yaml files) that specify the pipeline, data storage, and logging structure. The idea draws inspiration from the Pangeo-Forge Project which facilitates the Extraction, Transformation, Loading (ETL) of earth science geospatial datasets from traditional repositories to analysis-ready, cloud-optimized (ARCO) data stores Stern et al., 2022. The pangeo-forge recipes (which themselves are inspired by the conda-forge recipes conda-forge community, 2015) provide a model of how the data should be accessed and transformed, and the project has garnered numerous recipes from the community.

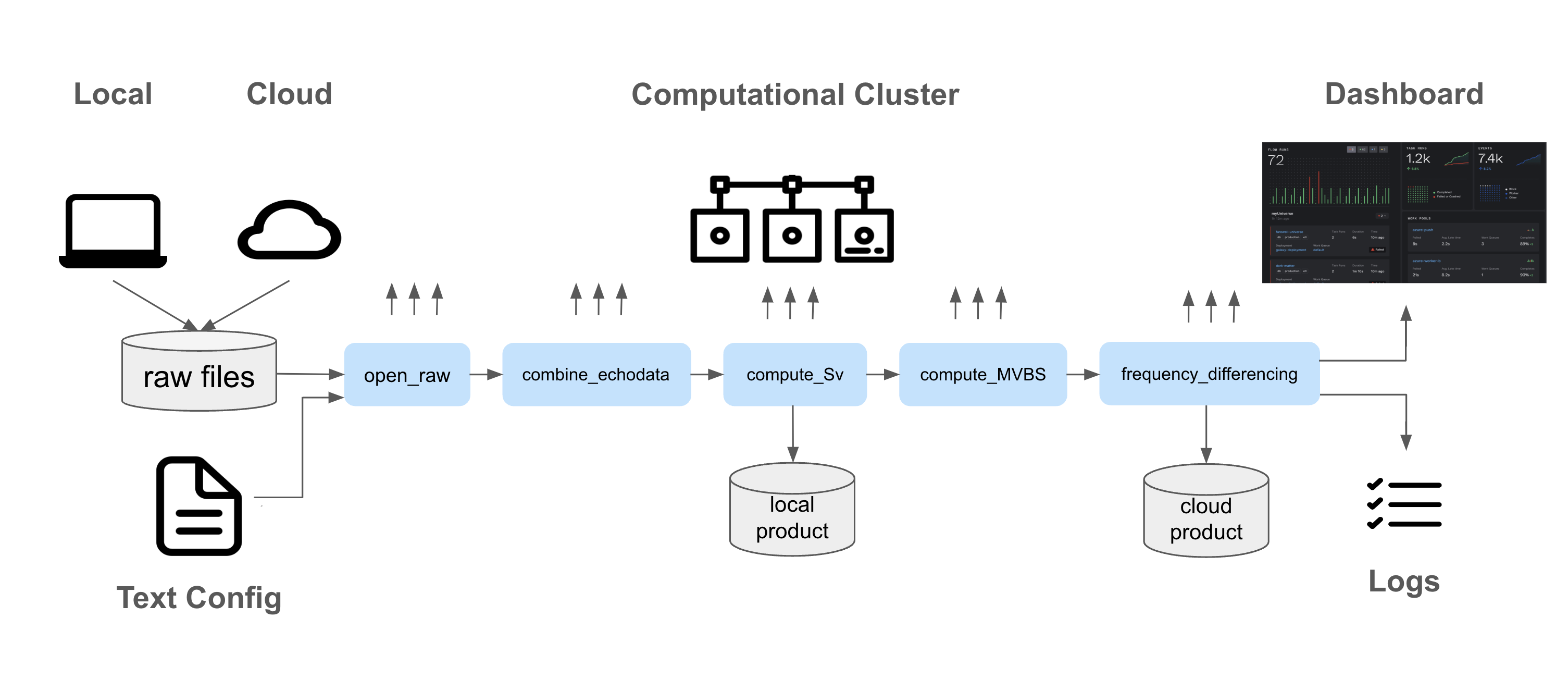

While Pangeo-Forge’s focus is on transformation from netcdf Rew & Davis, 1990 and hdf5 The HDF Group, n.d. formats to zarr, echodataflow’s aim is to support full echosounder data processing and analysis pipelines: from instrument-generated raw data files to data products which contain acoustically-derived biological estimates, such as abundance and biomass. echodataflow leverages Prefect Prefect, 2024 to abstract data and computation management. In Figure 3 we provide an overview of echodataflow’s framework. At the center we see several steps of an echosounder data processing pipeline: open_raw, combine_echodata, compute_Sv, compute_MVBS, frequency_differencing, which produce echo classificaton results using a simple threshold-based criterion. All these functions exist in the echopype package, and are wrapped by echodataflow into pre-defined stages. Prefect executes the stages on a Dask cluster which can be started locally or can be externally set up. These echopype functions already support distributed operations with Dask, and thus the integration with Prefect within echodataflow is natural. Dask clusters can be set up on a variety of platforms: local computers, cloud virtual machines, kubernetes Kubernetes, 2024 clusters, or HPC clusters (via dask-jobqueue Dask JobQueue, 2024), etc. and allow abstraction from the computing infrastructure. The input datasets, intermediate data products, and final data products can live in different storage systems (local/cloud) and Prefect’s block feature provides seamless, provider-agnostic, and secure integration with them. Workflows can be executed and monitored through Prefect’s dashboard, while logging of each function is handled by echodataflow.

Figure 3:Echodataflow Framework: The above diagram provides an overview of the echodataflow framework: the objective is to fetch raw files from a local filesystem/cloud archive, process them through several stages of an echosounder data workflow using a cluster infrastructure, and store both intermediate and final data products. In echodataflow the workflow is executed based on text configurations, and logs are generated for the individual processing stages. Prefect handles the execution of the tasks on the cluster and provides tools for monitoring the workflow runs.

3.1Why Prefect?¶

We chose Prefect among other Python workflow orchestration frameworks such as Apache Airflow Apache Airflow, 2024, Dagster Dagster, 2024, Argo Argo Workflows, 2024, Luigi Luigi, 2024. While most of these tools provide flexibily and level of abstraction suitable for executing fisheries acoustics pipelines, we selected Prefect for the following reasons:

- Prefect accepts dynamic workflows which are specified at runtime and do not require to follow a Directed Acyclic Graph, which can be restricting and difficult to implement.

- In Prefect, Python functions are first class citizens, thus building a Prefect workflow does not deviate substantially from traditional science workflows composed of functions.

- Prefect integrates with a

daskcluster, andechopypeprocessing functions are already usingdaskto scale operations. - Prefect’s code runs similarly locally as well as on cloud services.

- Prefect’s monitoring dashboard is open source, can be run locally, and is intuitive to use.

We next describe in more detail the components of the workflow lifecycle.

4Workflow Configuration¶

The main goal of echodataflow is to allow users to configure an echosounder data processing pipeline through editing configuration “recipe” templates. echodataflow can be configured through three templates: datastore.yaml which handles the data storage locations, pipeline.yml which specifies the processing stages, and logging.yaml which sets the logging format.

4.1Data Storage Configuration¶

Below we show an example file datastore.yaml with a data storage configuration for a ship survey. In this scenario the goal is to process data from the Joint U.S.-Canada Integrated Ecosystem and Pacific Hake Acoustic Trawl Survey Northwest Fisheries Science Center, Fishery Resource Analysis and Monitoring Division, 2022 which are publicly available on an AWS S3 bucket hosted by NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information Acoustics (NCEA) Archive Wall, 2016. The archive contains data from many surveys dating back to 1991 (~280TB). The configuration allows to pass parameters specifying the ship, survey, and sonar model names and select the subset of files belonging only to the survey of interest. The output destination is set to a private S3 bucket belonging to the user (within an AWS account different from the input one), and the credentials are passed through a block_name. The survey contains ~4000 files, and one can set the group option to combine the files into survey-specific groups: based on the transect information provided in the transect_group.txt file. One can further use regular expressions to subselect other subgroups based on needs.

# datastore.yaml

name: Bell_M._Shimada-SH1707-EK60

sonar_model: EK60

raw_regex: (.*)-?D(?P<date>\w{1,8})-T(?P<time>\w{1,6})

args:

urlpath: s3://ncei-wcsd-archive/data/raw/{{ ship_name }}/{{ survey_name }}/{{ sonar_model }}/*.raw

parameters:

ship_name: Bell_M._Shimada

survey_name: SH1707

sonar_model: EK60

storage_options:

anon: true

group:

file: ./transect_group.txt

storage_options:

block_name: echodataflow-aws-credentials

type: AWS

group_name: default_group

json_export: true

raw_json_path: s3://echodataflow-workground/combined_files/raw_json

output:

urlpath: <YOUR-S3-BUCKET>

overwrite: true

retention: false

storage_options:

block_name: echodataflow-aws-credentials

type: AWS4.2Pipeline Configuration¶

The pipeline configuration file’s purpose is to list the stages of the processing pipeline and the computational set-up for their execution. Below we show an example pipeline.yaml file which cofigures a pipeline with several stages: open_raw, combine_echodata, compute_Sv, compute_MVBS. Each stage is executed as a separate Prefect subflow (a component of a Prefect workflow), and one can specify additional options on whether to store the raw files. echodataflow requires access to a Dask cluster: it can be either created on the fly by setting the use_local_dask to true, or an IP address of an already running cluster can be provided. Individual stages may require different cluster configurations to efficiently execute the tasks. Those can be specified with the additional prefect_config option through which the user can set a specific Dask task runner or the number of retries. Managing retries is essential for handling transient failures, such as connectivity issues, ensuring the stages can be re-executed without any manual interference if a failure occurs.

# pipeline.yaml

active_recipe: standard

use_local_dask: true

n_workers: 4

scheduler_address: tcp://127.0.0.1:61918

pipeline:

- recipe_name: standard

stages:

- name: echodataflow_open_raw

module: echodataflow.stages.subflows.open_raw

options:

save_raw_file: true

use_raw_offline: true

use_offline: true

prefect_config:

retries: 3

- name: echodataflow_combine_echodata

module: echodataflow.stages.subflows.combine_echodata

options:

use_offline: true

- name: echodataflow_compute_Sv

module: echodataflow.stages.subflows.compute_Sv

options:

use_offline: true

- name: echodataflow_compute_MVBS

module: echodataflow.stages.subflows.compute_MVBS

options:

use_offline: true

external_params:

range_meter_bin: 20

ping_time_bin: 20S4.3Logging Configuration¶

By default, the outcomes of each stage are logged. The logs can be stored in .json or plain text files, and the format of the entries can be specified in the configuration file as displayed below. The json format allows searching through the logs for a specific key.

# logging.yaml

version: 1

disable_existing_loggers: False

formatters:

json:

format: '[%(asctime)s] %(process)d %(levelname)s %(mod_name)s:%(func_name)s:%(lineno)s - %(message)s'

plaintext:

format: '[%(asctime)s] %(process)d %(levelname)s %(mod_name)s:%(func_name)s:%(lineno)s - %(message)s'

handlers:

logfile:

class: logging.handlers.RotatingFileHandler

formatter: plaintext

level: DEBUG

filename: echodataflow.log

maxBytes: 1000000

backupCount: 3

loggers:

echodataflow:

level: DEBUG

propagate: False

handlers: [logfile]In this case the logs are stored in the plain text file echodataflow.log. Below we show an example of output logs.

[2024-06-06 17:32:08,945] 51493 ERROR apply_mask.py:EK60_SH1707_Shimada2_applymask.zarr:147 - Computing apply_mask

[2024-06-06 17:32:08,946] 51493 ERROR file_utils.py:file_utils:147 - Encountered Some Error in EK60_SH1707_Shimada0

[2024-06-06 17:32:08,946] 51493 ERROR file_utils.py:file_utils:147 - 'source_ds' must have coordinates 'ping_time' and 'range_sample'!

[2024-06-06 17:32:08,946] 51493 ERROR file_utils.py:file_utils:147 - Encountered Some Error in EK60_SH1707_Shimada1

[2024-06-06 17:32:08,946] 51493 ERROR file_utils.py:file_utils:147 - 'source_ds' must have coordinates 'ping_time' and 'range_sample'!

[2024-06-06 17:32:08,946] 51493 ERROR file_utils.py:file_utils:147 - Encountered Some Error in EK60_SH1707_Shimada2

[2024-06-06 17:32:08,946] 51493 ERROR file_utils.py:file_utils:147 - 'source_ds' must have coordinates 'ping_time' and 'range_sample'!In Section 7, we provide more information on logging options.

5Workflow Execution¶

To convert a scientific pipeline into an executable Prefect workflow, one needs to organize its components into flows, sublfows, and tasks (the key objects of Prefect’s execution logic). Usually, the stages of a pipeline are organized into flows and subflows, while the individual pieces of work within the stage are organized into tasks. In practice, flows, subflows, and tasks are all Python functions, and they differ in how we want to execute them (e.g. concurrently/sequentially, w/o retries), and what we want to track during execution (e.g. input/outputs, state logging, etc.). In echodataflow we organize the typical echosounder processing stages into subflows (flows within the main workflow), while the operations on different files (or groups of them) are individual tasks. We describe how functions are organized in the open_raw stage, which reads the files from raw format, parses the data, and writes them into a zarr format. The echodataflow_open_raw function is decorated as a flow, and is one of many subflows of the full workflow. This function processes all files.

@flow

@echodataflow(processing_stage="Open-Raw", type="FLOW")

def echodataflow_open_raw(

groups: Dict[str, Group], config: Dataset, stage: Stage, prev_stage: Optional[Stage]

):

"""

Process raw sonar data files and convert them to zarr format.

Args:

config (Dataset): Configuration for the dataset being processed.

stage (Stage): Configuration for the current processing stage.

prev_stage (Stage): Configuration for the previous processing stage.

Returns:

List[Output]: List of processed outputs organized based on transects.echodataflow_open_raw contains a loop which iterates through all file groups and applies the process_raw function which operates on a single group and is decorated as a task. All tasks will be executed on the Dask cluster.

for name, gr in groups.items():

for raw in gr.data:

new_processed_raw = process_raw.with_options(

task_run_name=raw.file_path, name=raw.file_path, retries=3

)

future = new_processed_raw.submit(raw, gr, working_dir, config, stage)

futures[name].append(future)

@task()

@echodataflow()

def process_raw(

raw: EchodataflowObject, group: Group, working_dir: str, config: Dataset, stage: Stage

):

"""

Process a single group of raw sonar data files.6Workflow Monitoring¶

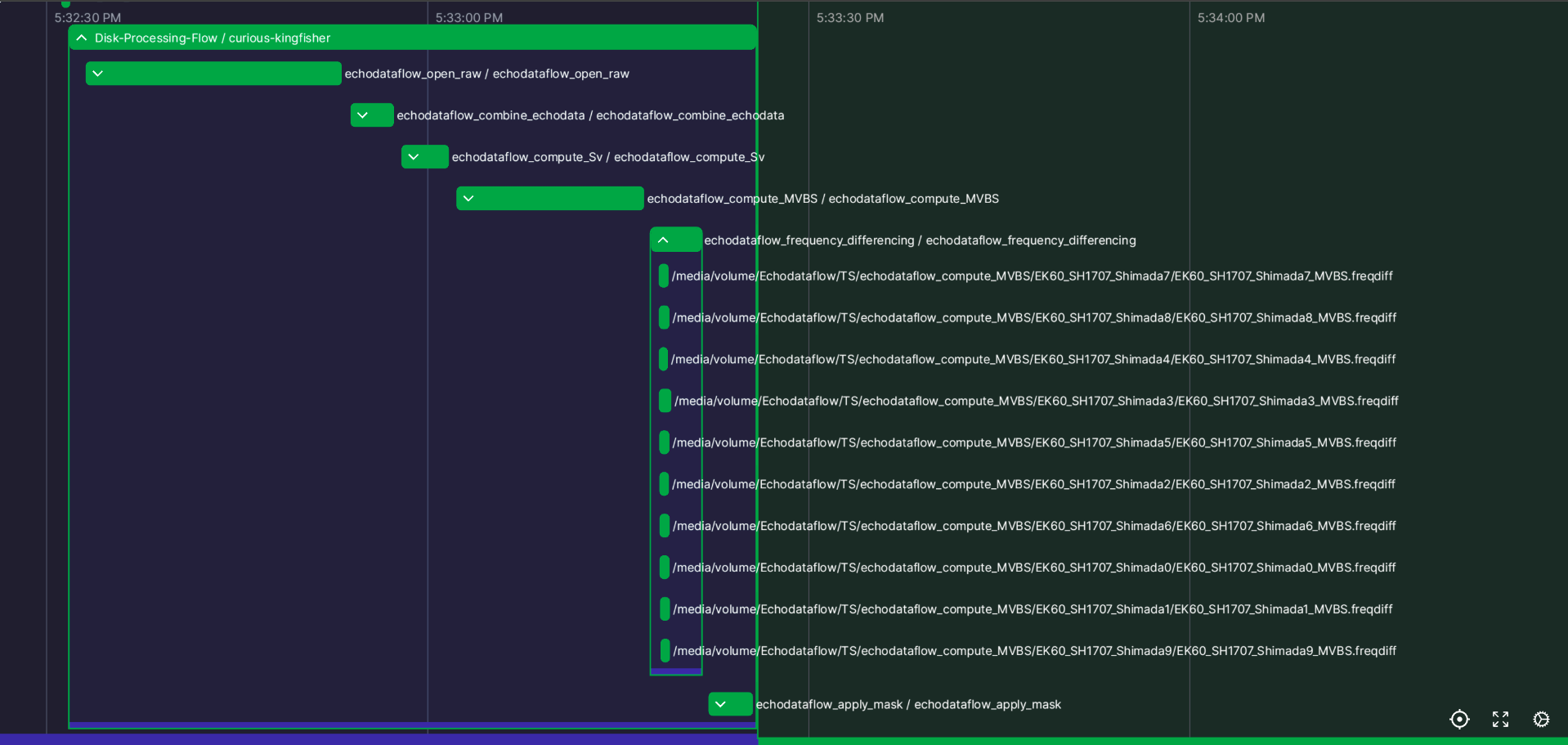

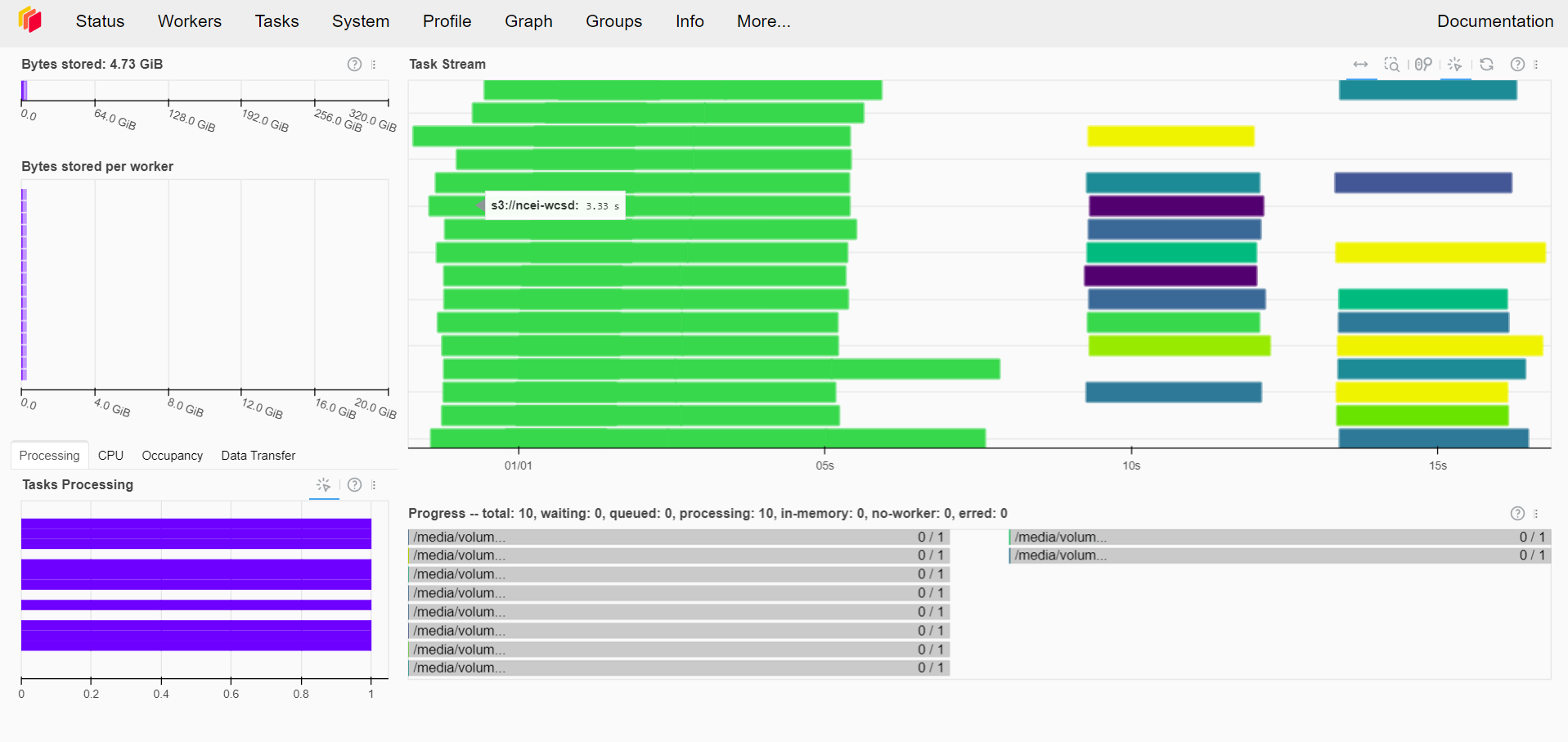

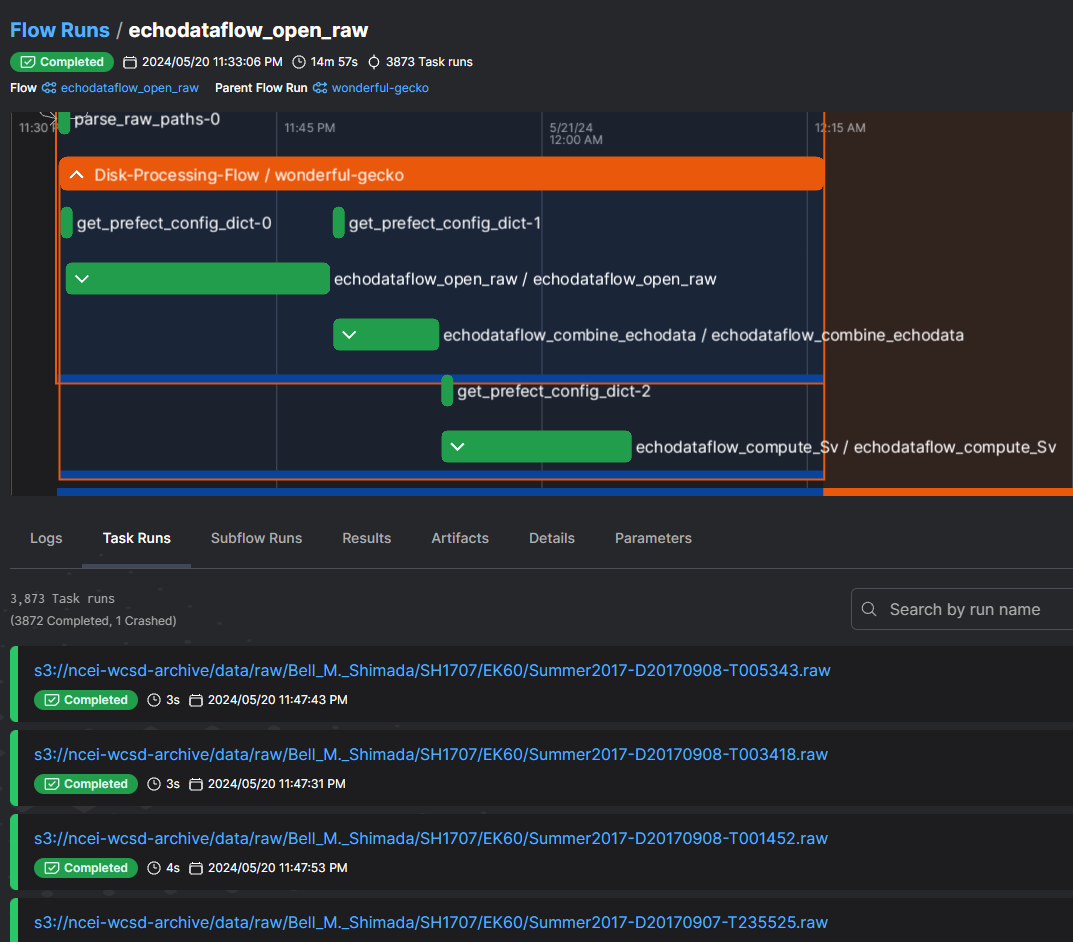

One of the main advantages of using orchestration frameworks is that they usually provide tools to monitor the workflow execution. The integration with Prefect allows leveraging Prefect’s dashboard (Prefect UI) for monitoring the execution of the flows. The dashboard can be run locally and within Prefect’s online managed system (Prefect Cloud). The local version provides an entirely open source framework for running and monitoring workflows. Figure 4 shows the view of completed runs within the dashboard. The progress can be monitored while the flows are in progress.

Figure 4:Flow Runs: Log of completed runs in Prefect UI. The stages (subflows) are executed sequentially. One can expand the view of an individual flow and see the tasks computed (asynchronously) within it.

Further, one can also view the progress of the execution of the tasks on the Dask cluster.

Figure 5:Dask Dashboard: The execution of the tasks on the Dask cluster can also be monitored through the Dask dashboard.

7Workflow Logging¶

Processing large data archives requires a robust logging system to identify at which step and for which files the processing has failed. Locating the issues allows to set a path forward to resolve them: either through improving the robustness of the individual libraries performing the processing steps, or through identifying the artifacts of the data which are incompatible with the existing pipeline. To address this, we provide several approaches:

- Basic Logging with Dask Worker Streams: this approach configures Dask worker streams to handle

echodataflowlogs, which is straightforward if exact log order is not crucial. - Centralized Logging with Amazon CloudWatch Amazon Cloudwatch, n.d.: this approach centralizes all logs for easy access and analysis. It can be useful when users are already utilizing AWS.

- Advanced Logging with Apache Kafka Apache Kafka, n.d. and Elastic Stack Elastic Stack, n.d. (Elasticsearch, Kibana, Beats, Logstash): this approach leverages Kafka for log aggregation and Elastic Stack for log analysis and visualization, offering a robust solution for those who can maintain the infrastructure, for example data center managers.

By default if logging is not configured, all the worker messages are directed to the application console. The order of logs may not be preserved since logs are written once control returns from the Dask workers to the main application.

8Workflow Deployment¶

8.1Notebook¶

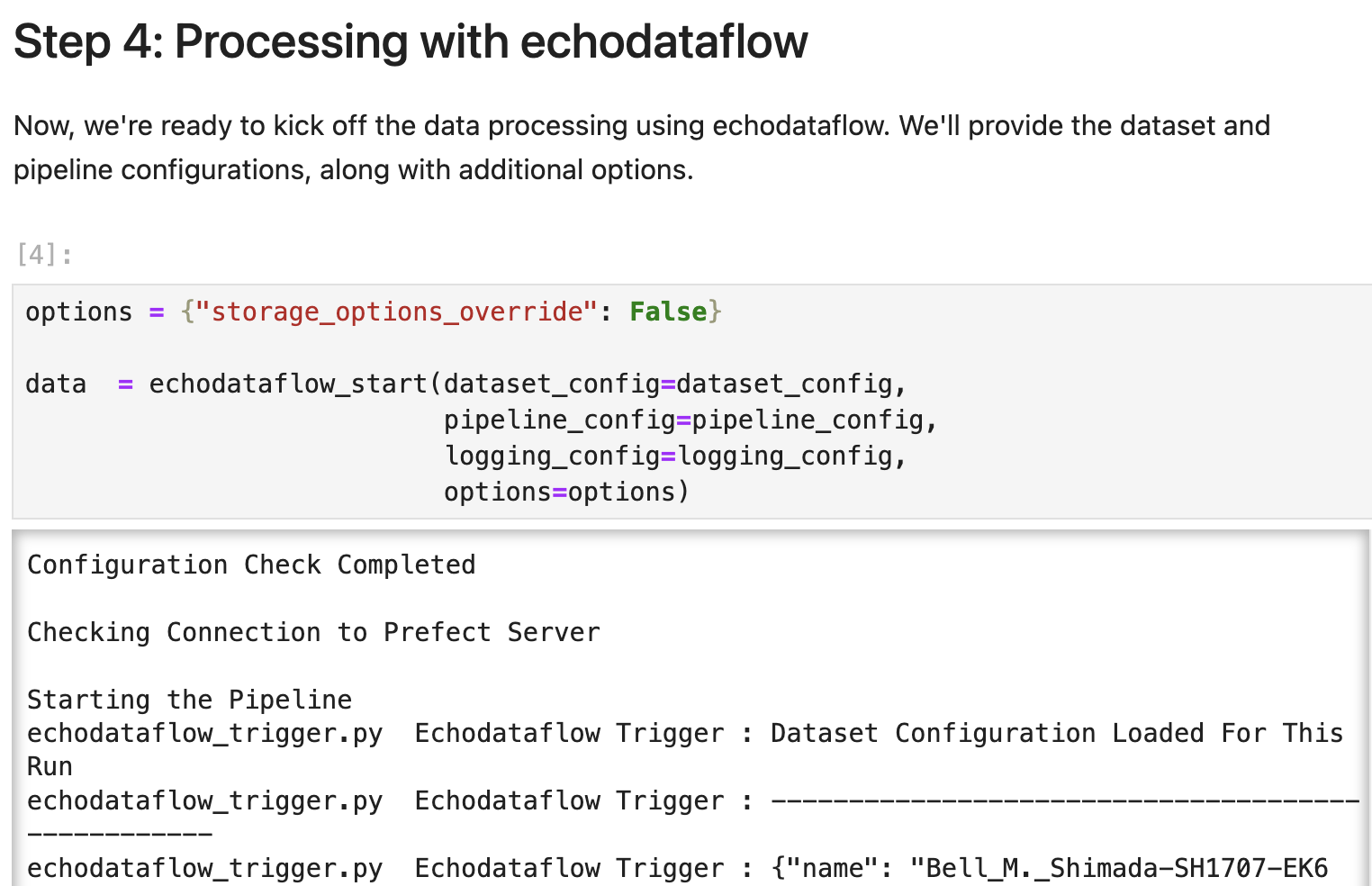

echodataflow can be directly initiated within a Jupyter notebook, which makes development interactive and provides a work environment familiar to researchers. One can see how the workflow is initiated within the Jupyter cell in Figure 6.

Figure 6:Initiating echodataflow in a Jupyter Notebook: Once one has a set of “recipe” configuration files, they can initiate the workflow in a notebook cell with the echodataflow_start command.

We provide two demo notebooks: one for execution on a local machine and another one for execution on AWS.

8.2Docker¶

We facilitate the deployment of echodataflow on various platforms by building a Docker image from which one can launch a container with all required components and the user can access the workflow dashboard on the corresponding port.

docker pull blackdranzer/echodataflow

prefect server start

docker run --network="host" -e PREFECT_API_URL=http://host.docker.internal:4200/api blackdranzer/echodataflowUpon execution, the user can readily access the Prefect UI dashboard and run workflows from there.

We also provide a Docker image for initiating logging with Kafka and Elastic Stack, thus streamlining the configuration of several tools.

9Command Line Interface¶

We provide a command line interface which supports credential handling, and several additional features for managing workflows: stage addition and rule validation.

9.1Adding Stages¶

Currently, most major functionalities in the echopype package are wrapped into stages: open_raw, add_depth, add_location, compute_Sv, compute_TS, compute_MVBS, combine_echodata, frequency_differencing, apply_mask.

We provide tools to generate boilerplate template configuration based on the existing stages. Here is an example to add a stage:

echodataflow gs <stage_name>For instance, to generate a boilerplate configuration for the compute_Sv stage, one would use:

echodataflow gs compute_SvThis command creates a template configuration file for the specified stage, allowing to customize and integrate it into a workflow. The generated file includes:

- a flow: it orchestrates the execution of all files that need to be processed, either concurrently or in parallel, based on the configuration.

- a task (helper function): it assists the flow by processing individual files.

9.2Rule Validation¶

Scientific workflows often have stages that cannot be executed until other stages have completed. Those conditions can be set through echodataflow client during the initialization process and are stored in a echodataflow_rules.txt file:

echodataflow_open_raw:echodataflow_compute_Sv

echodataflow_open_raw:echodataflow_combine_echodata

echodataflow_open_raw:echodataflow_compute_TS

echodataflow_combine_echodata:echodataflow_compute_Sv

echodataflow_compute_Sv:echodataflow_compute_MVBSThese rules dictate the sequence in which stages should be executed, ensuring that each stage waits for its dependencies to complete. They can be set through the echodataflow rules -add ... command.

9.2.1Aspect-Oriented Programming (AOP) for Rule Validation¶

In echodataflow, we adopt an aspect-oriented programming Kiczales et al., 1997 approach for rule validation. This is achieved using a decorator that can be applied to functions to enforce rules and log function execution details. The echodataflow decorator logs the entry and exit of a decorated function and modifies the function’s arguments based on the execution context. This supports two types of execution: “TASK” and “FLOW”.

Example Usage:

@echodataflow(processing_stage="StageA", type="FLOW")

def my_function(arg1, arg2):

# Function code here

passIn the example, the echodataflow decorator ensures that the function my_function is executed within the context of “StageA” as a “FLOW”, checking for dependencies and logging relevant information.

10Example Use Case: Processing Ship Survey Data from an Archive¶

We demonstrate a workflow processing all acoustic data for the 2017 Joint U.S.-Canada Integrated Ecosystem and Pacific Hake Acoustic Trawl Survey through a few routine processing stages. The survey spans a period of 06/15/2017 - 09/13/2017, covering the entire west coast of the US and Canada. Figure 1(a) shows a map of a typical transect schedule of the survey. Raw acoustic data are collected continuously while the ship is in motion, resulting in a total of 3873 files collected with a total size of 93 GB. The raw files are archived by the NOAA NCEI Water Column Sonar Data Archive and are publicly accessible on their Amazon Web Services S3 bucket (https://

- Convert raw files to cloud-native

zarrformat following closely a community convention Lee et al., 2021, Macaulay & Peña, 2018 - Combine multiple individual

zarrfiles within a continuous transect segment into a singlezarrfile - Compute Sv: calibrate the measured acoustic backscatter data to volume backscattering strength (Sv, unit: dB re 1 m-1)

Once data are converted to Sv, they are easy to manipulate, as the data are stored in an xarray data array and are smaller than that of the original data. The final dataset can be served as an analysis-ready data product to the community. It can be beneficial to store also intermediate datasets at different processing stages: for example, preserving the converted raw files in the standardized zarr format allows users to regenerate any of the following stages with different groupings or resolution, without having to fetch and convert raw data again.

The execution of the workflow with echodataflow allowed us to monitor the progress of all files Figure 7: 3872 files were successfully processed, and 1 failed. Most importantly, the failure did not block the execution of the other files, and a log was generated for the stage and the filename for which the error occurred. This experiment serves as a confirmation that the transition from local development to a full production pipeline with echodataflow can indeed be smooth.

Figure 7:Processing full 2017 Survey Data: 1/3873 files failed at the open_raw stage, but this did not impact the entire pipeline. As shown, other files were processed successfully through all stages.

11Future Development¶

Our immediate goal is to provide more example workflow recipes integrating other stages of echosounder data processing, such as machine learning prediction, training dataset generation, biomass estimation, interactive visualization, etc. We will demonstrate utilizing functionalities from a suite of open source Python packages (echoregions Nguyen et al., 2023 for reading region annotations and creating corresponding masks, echopop Lucca et al., 2024 for combining acoustic data with biological “ground truth” into biomass estimation, echoshader Lei et al., 2024 for echogram and map dashboard visualization) in building workflows for the Pacific Hake Survey: both in a historical and near-realtime on-ship data processing context. We aim to streamline the stage addition process. We will further investigate how to improve memory management and caching between and within stages to optimize for different scenarios. There is growing interest in the fisheries acoustics community to share global, accessible, and interoperable datasets ICES Working Group on Global Acoustic Interoperable Network (GAIN), n.d., and to agree on community data standards and definitions of processing levels Macaulay & Peña, 2018, Echosounder Data Processing Levels, n.d.. As those mature we will align them with existing stages in echodataflow, which will support building interoperable datasets whose integration will push us to study bigger and more challenging questions in fisheries acoustics.

12Beyond Fisheries Acoustics¶

Echodataflow was designed to facilitate fisheries acoustics workflows, but the structure can be adapted to data processing pipelines in other scientific communities. The key aspects are to identify the potential stages of the workflows and associated Python packages/functions that implement them, and to design the structure of the configuration files. The other aspects such as logging, deployment, monitoring, new-stage integration are domain-agnostic. Processing pipelines that require manipulation of large labeled arrays can directly benefit from the Dask cluster integration and are prevalent in the research community. Our use case of regrouping data based on time segments is a common need within scientific settings in which the file unit level of the instrument is not aligned with the unit level of analysis, and requires further reorganization and potential resampling and regridding along certain coordinates. We hope it can serve as a guide on how to build configurable, reproducible, and scalable workflows in new scientific areas.

We thank the Fisheries Engineering and Acoustic Technologies team at the NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center: Julia Clemons, Alicia Billings, Rebecca Thomas, Elizabeth Phillips for introducing us to the Pacific Hake Survey operations and the hake biomass estimation workflow.

This work used cpu compute and storage resources at Jetstream2 through allocation AGR230002 from the Advanced cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS) program Hancock et al., 2021, Boerner et al., 2023, which is supported by National Science Foundation grants #2138259, #2138286, #2138307, #2137603, and #2138296.

Funding

NOAA Award No. NA21OAR0110201, NOAA Award No. NA20OAR4320271 AM43, eScience Institute

Copyright © 2024 Staneva et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creators.

- AOP

- Aspect-Oriented Programming

- ARCO

- analysis-ready, cloud-optimized

- AWS

- Amazon Web Services

- ETL

- Extraction, Transformation, Loading

- GUI

- Graphics User Interface

- ML

- Machine Learning

- NCEI

- National Centers for Environmental Information

- NOAA

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- USV

- Uncrewed Surface Vessel

- NOAA National Center for Environmental Information. (2024). Understanding Our Ocean with Water-Column Sonar Data. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/e245977def474bdba60952f30576908f

- Saildrone. (2024). https://www.saildrone.com/

- DriX. (2024). https://www.ixblue.com/north-america/maritime/maritime-autonomy/uncrewed-surface-vehicles/

- Northwest Fisheries Science Center, Fishery Resource Analysis and Monitoring Division. (2022). The 2021 Joint U.S.-Canada Integrated Ecosystem and Pacific Hake Acoustic Trawl Survey: Cruise Report SH-21-06. 10.25923/0979-6D84

- Saildrone. (2019). US/Canada West Coast Fisheries. https://www.saildrone.com/technology/data-sets/west-coast-fisheries-2019

- Trowbridge, J., Weller, R., Kelley, D., Dever, E., Plueddemann, A., Barth, J. A., & Kawka, O. (2019). The Ocean Observatories Initiative. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6. 10.3389/fmars.2019.00074

- Echoview Software Pty Ltd. (n.d.). Echoview - Sound Knowledge. Retrieved October 4, 2020, from https://www.echoview.com/

- Korneliussen, R., Ona, E., Eliassen, I., Heggelund, Y., Patel, R., Godo, O. R., Giertsen, C., Patel, D., Nornes, E., Bekkvik, T., Knudsen, H. P., & Lien, G. (2006). The Large Scale Survey System - LSSS. Proceedings of the 29th Scandinavian Symposium on Physical Acoustics. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:204802910

- Ladroit, Y., Escobar-Flores, P. C., Schimel, A. C. G., & O’Driscoll, R. L. (2020). ESP3: An open-source software for the quantitative processing of hydro-acoustic data. SoftwareX, 12, 100581. 10.1016/j.softx.2020.100581

- Perrot, Y., Brehmer, P., Habasque, J., Roudaut, G., Behagle, N., Sarré, A., & Lebourges-Dhaussy, A. (2018). Matecho: An Open-Source Tool for Processing Fisheries Acoustics Data. Acoustics Australia, 46(2), 241–248. 10.1007/s40857-018-0135-x

- Harrison, L.-M. K., Cox, M. J., Skaret, G., & Harcourt, R. (2015). The R package EchoviewR for automated processing of active acoustic data using Echoview. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2. 10.3389/fmars.2015.00015

- Wall, C. C., Towler, R., Anderson, C., Cutter, R., & Jech, J. M. (2018). PyEcholab: An open-source, python-based toolkit to analyze water-column echosounder data. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 144(3), 1778–1778. 10.1121/1.5067860

- Lee, W.-J., Mayorga, E., Setiawan, L., Majeed, I., Nguyen, K., & Staneva, V. (2021). Echopype: A Python library for interoperable and scalable processing of water column sonar data for biological information. arXiv:2111.00187 [Eess]. 10.48550/arXiv.2111.00187

- open-ocean-sounding/echopy. (2024). https://github.com/open-ocean-sounding/echopy (Original work published 2021)

- Harris, C. R., Millman, K. J., van der Walt, S. J., Gommers, R., Virtanen, P., Cournapeau, D., Wieser, E., Taylor, J., Berg, S., Smith, N. J., Kern, R., Picus, M., Hoyer, S., van Kerkwijk, M. H., Brett, M., Haldane, A., del Río, J. F., Wiebe, M., Peterson, P., … Oliphant, T. E. (2020). Array programming with NumPy. Nature, 585(7825), 357–362. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2649-2