Echostack: A flexible and scalable open-source software suite for echosounder data processing

Abstract¶

Water column sonar data collected by echosounders are essential for fisheries and marine ecosystem research, enabling the detection, classification, and quantification of fish and zooplankton from many different ocean observing platforms. However, the broad usage of these data has been hindered by the lack of modular software tools that allow flexible composition of data processing workflows that incorporate powerful analytical tools in the scientific Python ecosystem. We address this gap by developing Echostack, a suite of open-source Python software packages that leverage existing distributed computing and cloud-interfacing libraries to support intuitive and scalable data access, processing, and interpretation. These tools can be used individually or orchestrated together, which we demonstrate in example use cases for a fisheries acoustic-trawl survey.

1Introduction¶

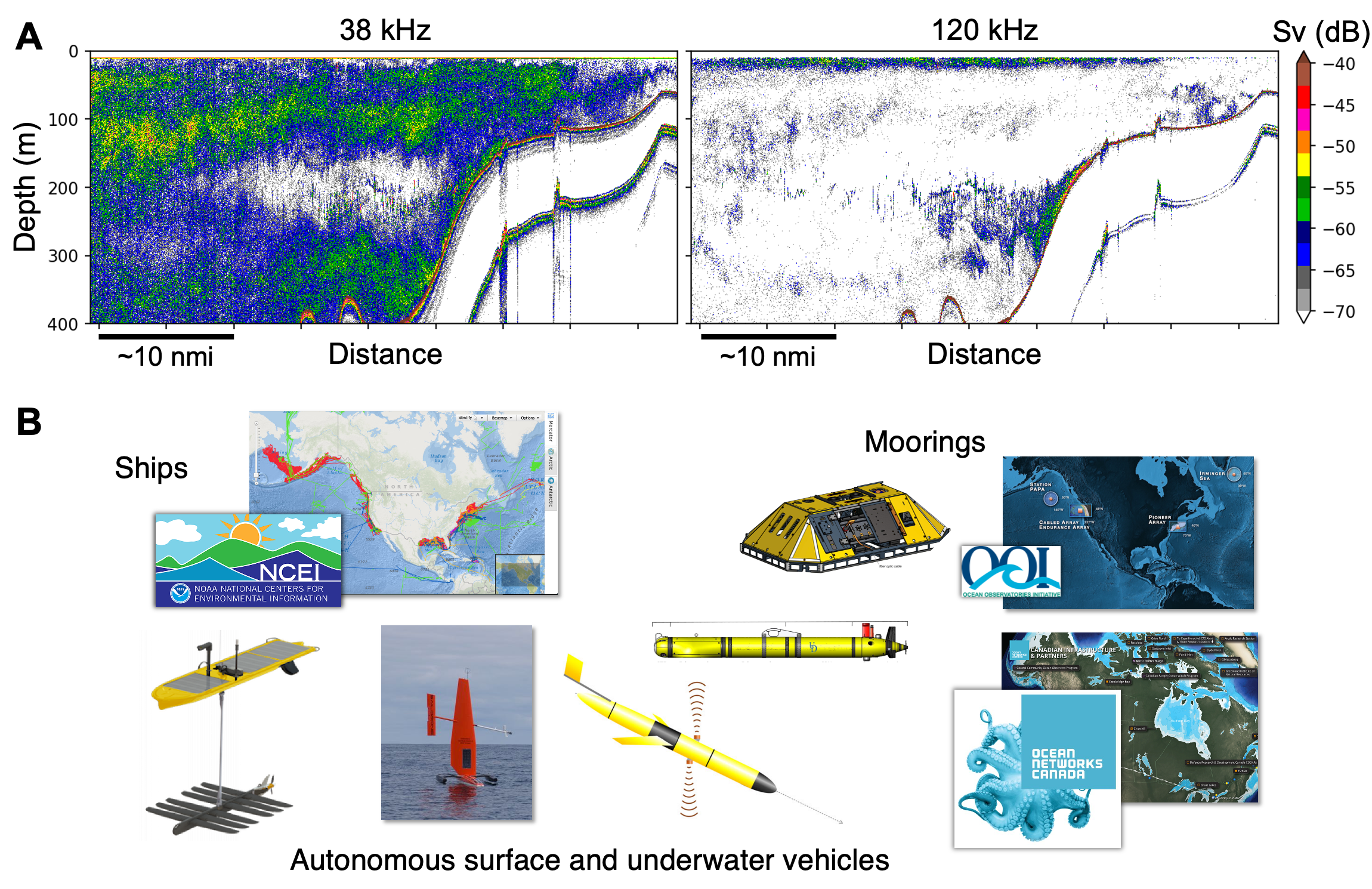

Echosounders are high-frequency sonar systems optimized for sensing fish and zooplankton in the ocean. By transmitting sound and analyzing the returning echoes, fisheries and ocean scientists use echosounders to “image” the distribution and infer the abundance of these animals in the water column Medwin & Clay, 1998Stanton, 2012Benoit-Bird & Lawson, 2016 Figure 1A. As a remote sensing tool, echosounders are uniquely suitable for efficient, continuous biological monitoring across time and space, especially when compared to net trawls that are labor-intensive and discrete in nature, or optical imaging techniques that are limited in range due to the strong absorption of light in water.

In recent years, echosounders have been installed widely on many ocean observing platforms Figure 1B, resulting in a deluge of data accumulating at an unprecedented speed from all corners of the ocean. These extensive datasets contain crucial information that can help scientists better understand the marine ecosystems and their response to the changing climate. However, the volume of the data (100s of GBs to TBs Wall et al., 2016) and the complexity of the problem (e.g., how large- scale ocean processes drive changes in acoustically observed marine biota Klevjer et al., 2016) naturally call for a paradigm shift in the data analysis workflow.

Figure 1:(A) Echograms (sonar images formed by aligning echoes of consecutive transmissions) at two different frequencies. Echo strength variation across frequency is useful for inferring scatterer identity. Sv denotes volume backscattering strength (units: dB re 1 m-1). (B) The variety of ocean observing platforms with echosounders installed.

It is crucial to have software tools that are developed and shared openly, scalable in response to data size and computing platforms, easily interoperable with diverse analysis tools and different types of oceanographic data, and straightforward to reproduce to facilitate iterative modeling, parameterization, and mining of the data. These requirements are challenging to meet by conventional echosounder data analysis workflows, which rely heavily on manual analysis on software packages designed to be used with Graphic User Interface (GUI) on a single computer [e.g., Korneliussen et al. (2006); Perrot et al. (2018); Ladroit et al. (2020); Echoview (https://

In this paper, we introduce Echostack, an open-source Python software suite aimed at addressing these needs by providing the fisheries acoustics and ocean sciences communities with tools for flexible and scalable access, organization, processing, and visualization of echosounder data. Echostack is a domain-specific adoption of the core libraries in the Pandata stack, such as Zarr, Xarray, and Dask Bednar & Durant, 2023. It streamlines the composition and execution of common echosounder data workflows, thereby allowing researchers to focus on the key interpretive stage of scientific data analysis. As echosounder data processing frequently requires combining heterogeneous data sources and models in addition to regular array operations, we designed the Echostack packages with modularity in mind, to 1) enable and facilitate broader code reuse, especially for routine processing steps that are often shared across echosounder data workflows Haris et al., 2021, and 2) promote flexible integration of domain-specific operations with more general analytical tools, such as machine learning (ML) libraries. The Echostack also provides a friendly on-ramp for researchers who are not already familiar with the scientific Python software ecosystem but possess domain expertise and can quickly benefit from “out-of-the-box” capabilities such as native cloud access and distributed computing support.

Below, we will discuss what the Echostack tools aim to achieve in Section 2, outline the functionalities of individual libraries in Section 3, demonstrate how Echostack tools can be leveraged in Section 4, and conclude with a forward-looking discussion in the Section 5 section.

2Design approach and considerations¶

2.1Goals and motivations¶

The development of the Echostack was motivated by our core goals to create software tools that can be:

- Easily leveraged to construct workflows tailored to different application scenarios,

- Easily integrated with new data analysis methodologies, and

- Easily scalable according to the available computing resources and platforms.

Traditionally, the bulk of echosounder data analysis takes place on shore in a post-processing scenario, based on the acoustic data and related biological information (e.g., animal community composition and sizes derived from net catches) collected at sea and stored on hard drives. More recently, thanks to increased access to high-bandwidth communication and powerful embedded processing, scenarios requiring real-time capabilities have emerged, including continuous streaming of data from long-term moorings e.g., Trowbridge et al., 2019 and close-loop, adaptive sampling on autonomous vehicles e.g., Moline et al., 2015. Similarly on the rise are the incorporation of new inference and ML methods into echosounder data analysis workflows e.g., Brautaset et al., 2020Choi et al., 2023Urmy et al., 2023Zhang et al., 2024, as well as a need for scalable and platform-agnostic computations that work out-of-the-box on systems ranging from personal computers to the cloud. The latter is particularly important for data workflows associated with ocean instruments such as echosounders, as both small and big data scenarios are common and equally important: On a sea-going research vessel, newly collected data are typically processed in small batches on a few local machines; in oceanographic data centers, however, large volumes of data need to be promptly ingested and made available for open use.

These requirements are challenging to fulfill by existing echosounder data processing software packages, but are in fact key advantages of the Pandata open-source Python stack. While some existing software packages do support real-time applications (e.g., Echoview live viewing, MOVIES3D real-time display) and allow the incorporation of new analysis methods e.g., Harrison et al., 2015, the exact code implementation may be limited by the data structures and access allowed in a given package, as opposed to the flexibility afforded by Pythonic programmatic composition. In terms of scalability, even though some existing packages can achieve out-of-core computation via memory mapping Korneliussen et al., 2006Ladroit et al., 2020, the natural and optional scalability across computing resources and platforms offered by Pandata libraries Bednar & Durant, 2023 significantly reduces the code implementation overhead.

2.2Other guiding principles¶

In addition to the above goals, our development was further guided by the following principles, with the long-term goal of catalyzing community collaboration and workflow transformation.

2.2.1Accessibile and interoperable data¶

Echosounder data have traditionally been viewed as a highly specialized, niche data type that are hard to use and interpret despite the wealth of biological information embedded in the datasets. This is in part due to the highly heterogeneous, instrument-specific echosounder data format, as well as the inherent complexity in interpreting acoustic backscatter data Stanton, 2012. We aim to provide convenient, open software tools that facilitate the creation of standardized data in a common, machine-readable format that is both easy to understand and conducive to integrative analysis with other oceanographic datasets.

2.2.2Reproducible and shareable workflow¶

Just like in many scientific domains, echosounder data analysis workflows are typically built by researchers working closely within a single group, although knowledge sharing and exchanges do occur in community conferences or workshops. As data volumes rapidly increase and the urgency to comprehensively understand marine ecosystem functions escalates with global warming, efficient and effective collaboration across groups has become crucial. Ensuring that analysis workflows can be easily reproduced and shared alongside open, standardized data is key to scaling up our collective capability to extract information from these data.

2.2.3Nimble code adjustments¶

As a domain-specific adaptation of the Pandata stack, we aim to develop and maintain a “shallow” and nimble stack: we employ only moderate layers of abstraction and encapsulation of existing functions and prioritize existing data structures unless modification is absolutely necessary. This allows new features, enhancements, or bug fixes in the underlying dependency libraries to be either naturally reflected (in cases when there are no breaking changes) or quickly incorporated (in cases when code changes are required) into the Echostack tools. This approach also keeps the code easily readable for potential contributors, even though the exact operations may be highly domain-specific.

3The Echostack packages¶

3.1Functional grouping for package organization¶

In light of our goals and design principles, we aim for the Echostack libraries to be modular software “building blocks” that can be mixed and matched, not only with other elements within Echostack but also with tools from the wider scientific Python software ecosystem. Rather than encapsulating all functionalities into a single, monolithic package like many existing echosounder data analysis software [e.g., Korneliussen et al. (2006); Echoview], the Echostack packages are organized based on functional groupings that emerge in typical echosounder data analysis workflows to enable flexible and selective installation and usage. Similar to the design concept of the Pandata tools, such grouping also allows each package in the Echostack to be independently developed and maintained according to natural variations of project focus and needs.

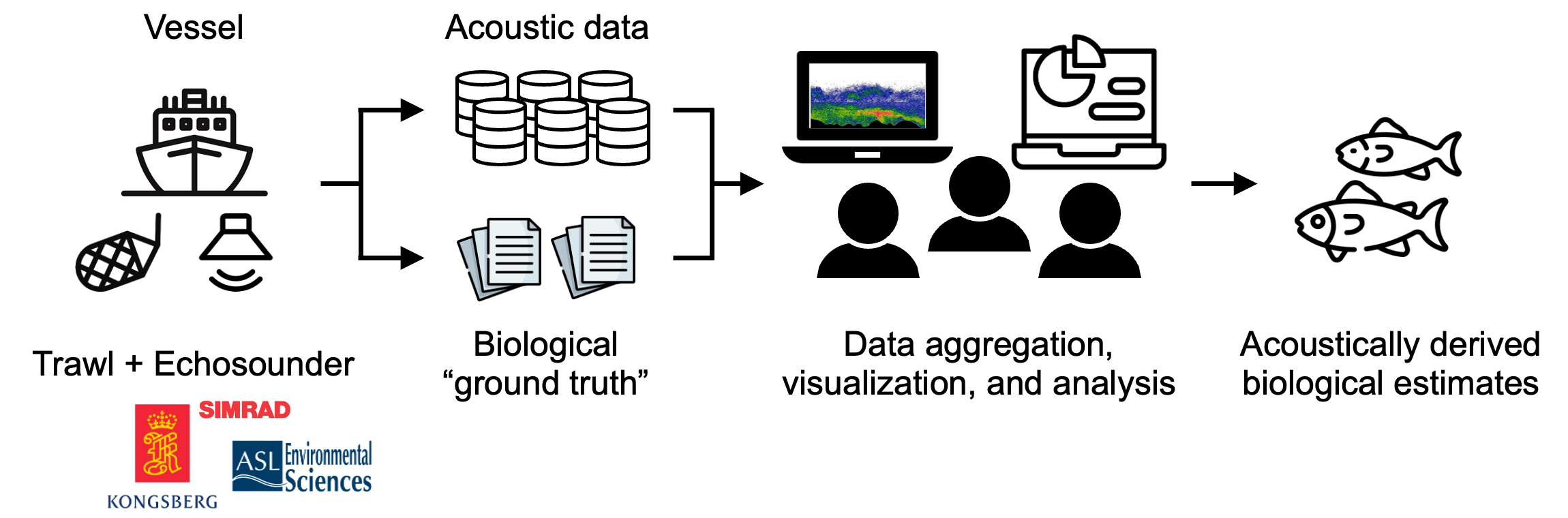

Typical echosounder data analysis workflows consist of the following common steps Figure 2:

- Read, align, and aggregate the acoustic data and associated biological data (the “ground truth” from in situ samples) based on temporal and/or spatial relationships;

- Infer the contribution of animals in different taxonomic groups to the total returned echo energy; and

- Derive distributions of population estimates (e.g., abundance or biomass) and behavior (e.g., migration) over space and time for the observed animals.

The resulting biological estimates are then used in downstream fisheries and marine ecological research and for informing resource management decisions. Also embedded in these steps are the needs for:

- Interactive visualization of echo data and/or derived estimates, at different stages of the workflow, which is crucial for understanding data and motivating downstream analyses; and

- Robust provenance tracking of data origin and processing steps, which enhances the reproducibility and shareability of the workflows.

Figure 2:Typical echosounder data analysis workflows.

In a fisheries acoustic-trawl survey – a typical use case – the overall goal is to estimate the abundance and biomass of important fish and zooplankton species using a combination of observational data and analytical models. The observational data include acoustic data collected by the echosounders and biological data (animal species and sizes, etc) collected by trawls. These data are linked in the acoustic inference step, which partitions the acoustic observation into contributions from different animal groups in the water column based on empirical models (which rely heavily on morphological features of animal aggregations visualized on the echogram), physics-based models (which rely heavily on spectral or statistical features of the echo returns), ML models (which can combine various data features depending on the model setup), or a mixture of the above.

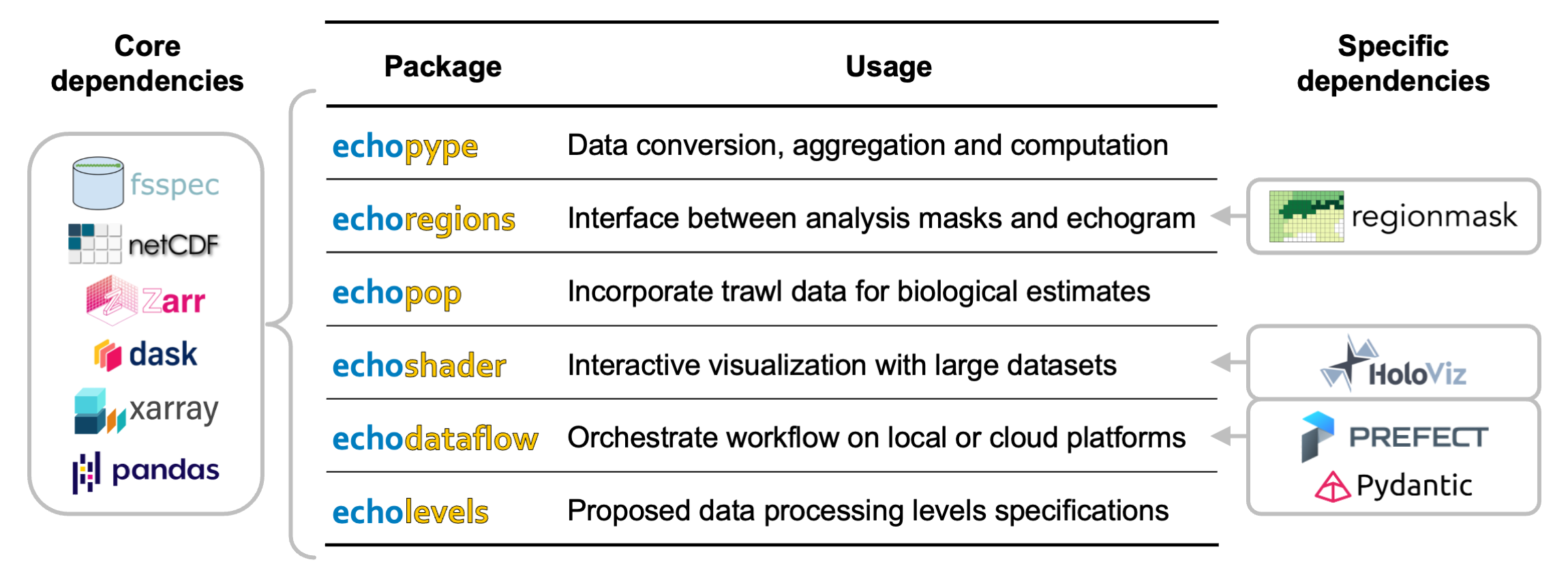

Based on the above, we identified natural punctuations in the typical workflows, and grouped computational operations that serve coherent high-level functionalities into separate packages Figure 3 that are described in the next section. The grouping decisions and the current implementations were driven by our own project goals to accelerate information extraction for a fisheries acoustic-trawl survey for Pacific hake (see Section 4 for detail) through ML and cloud technology. However, as the examples will show, these packages can be easily leveraged in different application scenarios.

Figure 3:The Echostack packages are modularized based on functional grouping of computational operations in echosounder data analysis workflows.

3.2Package functionalities¶

The Echostack includes five software packages (Echopype, Echoregions, Echopop, Echoshader, and Echodataflow) that each handles a specific set of functionalities in general echosounder data processing workflows Figure 3. In parallel, Echolevels provides specifications for a cascade of data processing levels from raw to highly processed data, to enhance data sharing and usage. The Echostack packages jointly relies on a set of core dependencies for interfacing with file systems (fsspec), data storage (netCDF and Zarr), and data organization and computation (Xarray, Pandas, and Dask). Additionally, some libraries have specific dependencies to support functionalities like interactive plotting (HoloViz), masking grids based on regions (Regionmask), and workflow configuration (Pydantic) and orchestration (Prefect), as shown in Figure 4.

The sections below provide brief descriptions of the functionalities of the Echostack packages, their current status, and future development plans.

Figure 4:Summary of the Echostack packages and key dependencies.

3.2.1Echopype¶

Echopype (https://

3.2.2Echoregions¶

Echoregions (https://

3.2.3Echopop¶

Echopop (https://

3.2.4Echoshader¶

Echoshader (https://

3.2.5Echodataflow¶

Echodataflow (https://

3.2.6Echolevels¶

Echolevels (https://

4Example use cases¶

In this section, we present three example use cases of the Echostack libraries under the application scenario of a fisheries acoustic-trawl survey. Here, we use the Joint U.S. and Canada Pacific Hake Integrated Ecosystem and Pacific Hake Acoustic Trawl Survey (aka the “Hake survey”) as an example, as we are familiar with its context and setup for our project to accelerate biological information extraction using ML and cloud technology. The Hake survey dates back to the late 1990s when echosounder technology was first widely adopted for fishery surveys. In recent years, this survey has occurred every odd-numbered year, covering the coastal waters, shelf break, and open ocean along the entire west coasts of the US and Canada Northwest Fisheries Science Center, Fishery Resource Analysis and Monitoring Division, 2022.

The example use cases presented below demonstrate how Echostack tools are leveraged in echosounder data analysis and management. The examples utilize both raw data files archived in a data center and near real-time data continuously generated from a ship-mounted echosounder. We show how these tools can be used in a mix-and-match manner with each other and with other tools in the scientific Python software ecosystem to achieve user goals. Note that not all Echostack libraries are used in all use cases, which highlights the advantage of modular package design based on functional grouping.

4.1Use case 1: Interactive data exploration and experimentation¶

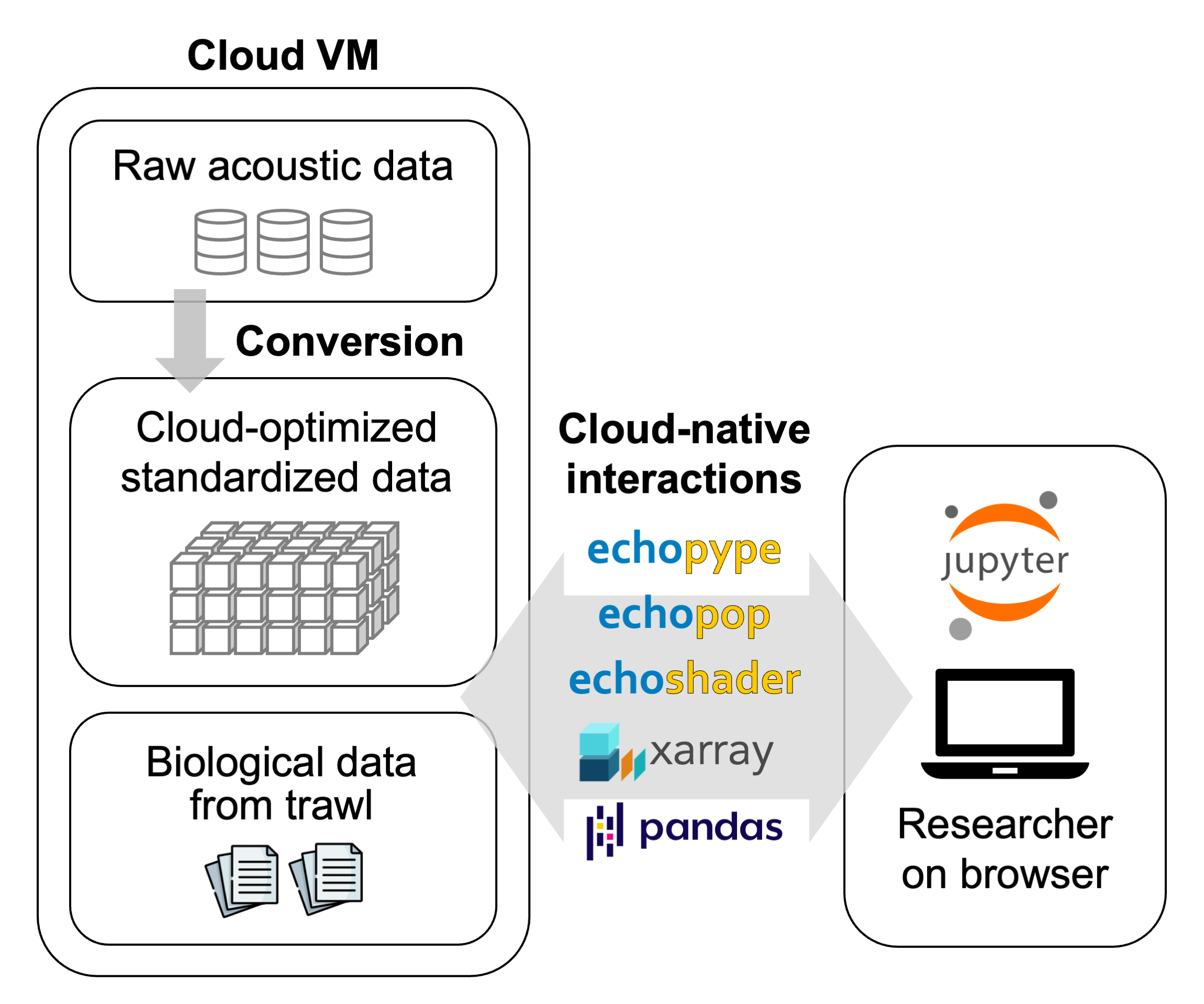

This is a common use case in which researchers interact with echosounder data through the browser-based Jupyter computing interface on a cloud virtual machine Figure 5. They first assemble a Zarr store consisting of calibrated echo data for a single survey transect by directly processing a collection of raw files from a data center server (Echopype). They then interactively visualize the data (Echoshader) and experiment with the influence of different data cleaning options (Echopype and custom functions) on the resulting acoustically inferred biomass of a fish species (Echopop). These experimentations help the research identify parameters for setting up batch processing across all survey transects.

Figure 5:Use case 1: Interactive data exploration and experimentation.

4.2Use case 2: A ship-to-cloud ML pipeline¶

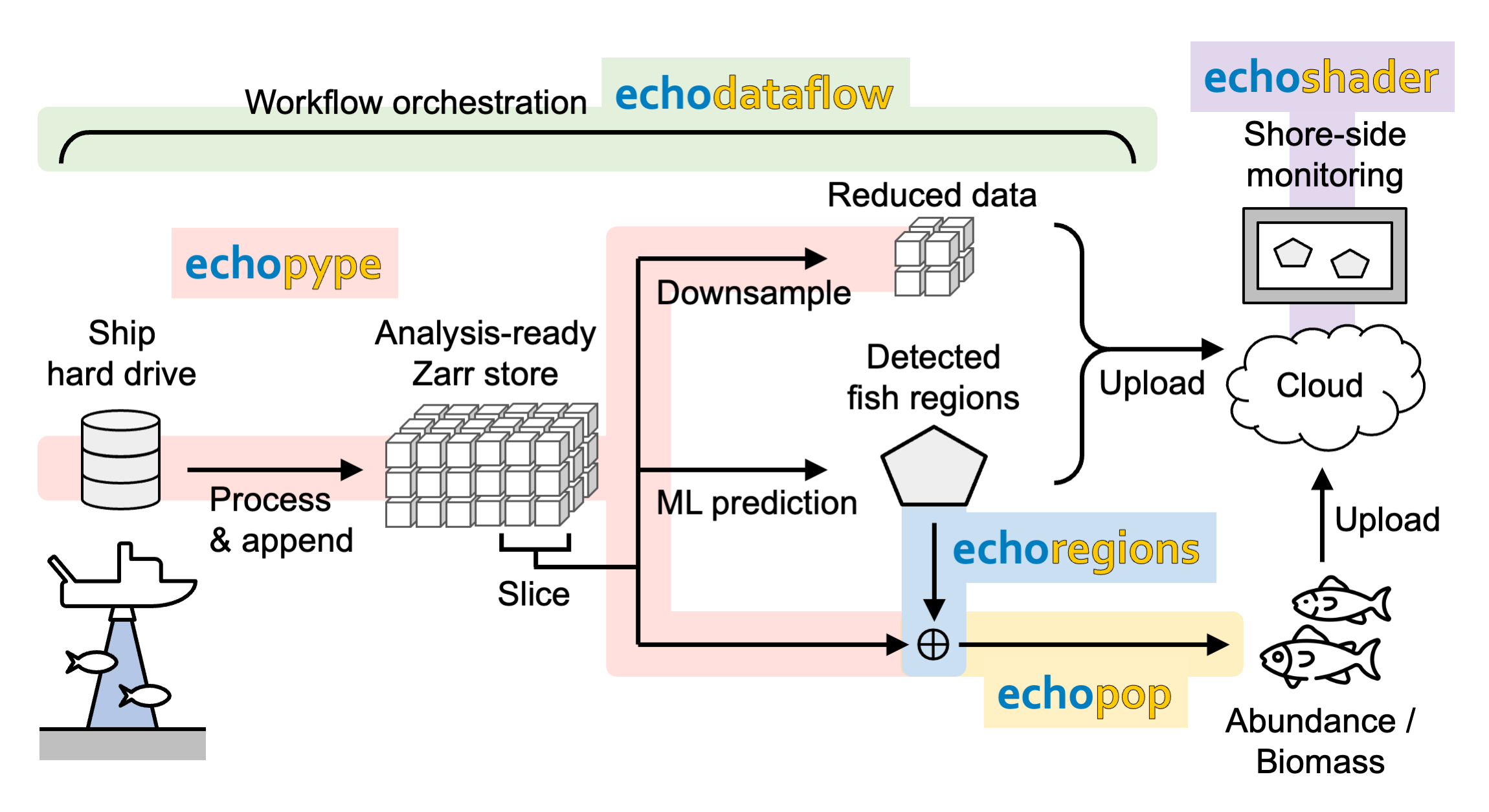

This is an experimental use case in which researchers construct a ship-to-cloud pipeline that uses an ML model to analyze ship echosounder data in near real-time and send the predictions and reduced data to the cloud for shore-side monitoring Figure 6. The pipeline is orchestrated by Echodataflow, which manages data organization actions triggered by new files and analysis-oriented actions through a scheduler. A “watchdog” monitors the ship hard drive for newly generated raw echosounder data files, and continuously converts, calibrates, regrids, and appends new echo data into a local Zarr store dedicated to ML analysis (Echopype). At regular intervals, the last section in the Zarr store is sliced and fed to an ML model to detect the occurrence of a target fish species on the echogram (custom functions). The echo data are applied with the ML predictions (Echoregions) and used to compute the abundance and biomass estimates (Echopop). The echo data slices are also further downsampled (Echopype) and sent to a cloud Zarr store for interactive visual monitoring (Echoshader). This pipeline paves the way for later optimization for an edge implementation on autonomous platforms.

Figure 6:Use case 2: A ship-to-cloud ML pipeline.

4.3Use case 3: Mass production of analysis-ready, cloud-optimized (ARCO) data products¶

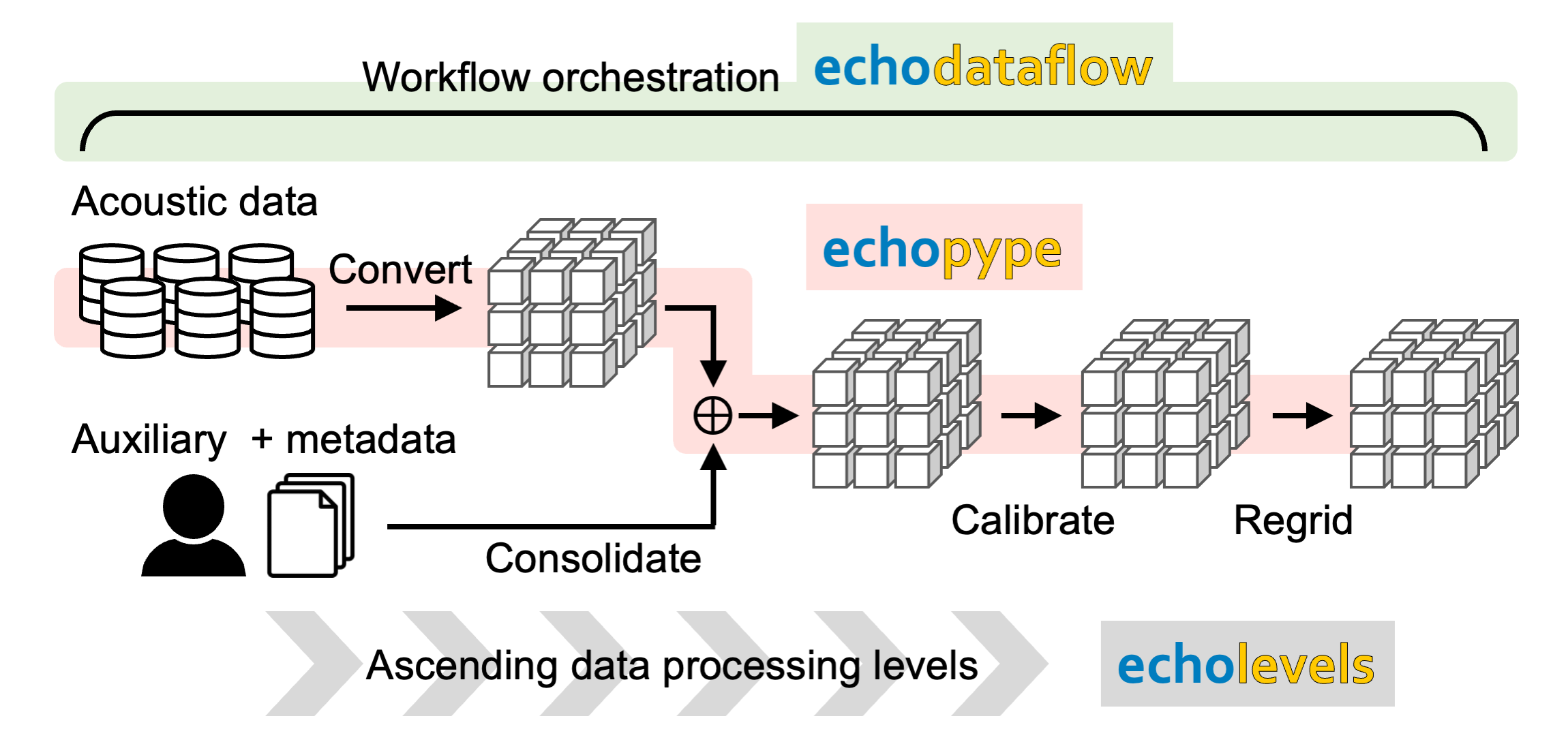

This is a use case in which researchers or data managers create analysis-ready, cloud-optimized (ARCO) echosounder data stores that can be readily drawn for analysis and experimentation Figure 7. The pipeline is orchestrated by Echodataflow, which handles the efficient distribution of bulk computing tasks, communicates with data sources and destinations, and automatically logs and retries any processing errors. In the pipeline, instrument-generated binary data files sourced from a data center progress through multiple processing steps and are enriched with auxiliary data and metadata that may not exist in the original binary form (Echopype). These steps span through multiple data processing levels (Echolevels), at which data products are stored with full provenance to maximize re-processing flexibility and usability. The data stores assembled under this use case can be easily leveraged by researchers in Use case 1 to jump start their experimentation of data cleaning parameters.

Figure 7:Use case 3: Mass production of cloud-optimized, analysis-ready data products

5Discussion¶

Echostack is an open-source software suite under active development. It will continue to evolve with the needs of the users and advancements in the scientific Python software ecosystem, in particular the Pandata and derived libraries in the wider geosciences domain. The Echostack tools were initially developed to address needs arising from our own research projects, but we quickly realized the potential value of these tools as open resources in the fisheries acoustic and ocean sciences communities. This paper serves as an interim report that describes our design considerations and discusses current capabilities and future plans together with three concrete use cases. Moving forward, we have two main goals: 1) enhancing Echostack features and performance, and 2) cultivating community user engagement. For the libraries, we aim to incorporate a wider set of echosounder data processing and visualization functions, ensure scalability with large datasets, improve documentation, and provide benchmark reports for library performance. For the community, we aim to broaden the discussion on development priorities and encourage code contribution from the user community, through intentional outreach efforts via both formal (conferences and workshops) and informal (interactions on code repositories and emails) channels. These goals are interdependent and form a positive feedback loop, as the more useful the software tools are, the more likely people will use it and contribute to its maintenance and development. The echosounder user community is diverse and includes members with a wide range of technical experiences and practical considerations, and would benefit from a suite of flexible tools that are both plug-and-play and customizable to meet specific requirements. It is our hope that the Echostack software packages can function as a catalyst for community-wide discussions and collaborations on advancing data processing workflow and information extraction in this domain.

We thank Alicia Billings, Dezhang Chu, Julia Clemons, Elizabeth Phillips, and Rebecca Thomas for discussions on code implementations and use cases, and Imran Majeed, Kavin Nguyen, Praneeth Ratna, and Brandyn Reyes for contributing to the code. The software development received funding support from NOAA Fisheries, NOAA Ocean Exploration, NSF, NASA, and the Gordon and Betty Moore and Alfred P. Sloan Foundations (MSDSE Environments), as well as engineering support from the University of Washington Scientific Software Engineering Center funded by Schmidt Futures as part of the Virtual Institute for Scientific Software.

Copyright © 2024 Lee et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creators.

- ARCO

- analysis-ready, cloud-optimized

- ML

- machine learning

- Medwin, H., & Clay, C. S. (1998). Fundamentals of acoustical oceanography. Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-487570-8.X5000-4

- Stanton, T. K. (2012). 30 years of advances in active bioacoustics: A personal perspective. Methods in Oceanography, 1–2, 49–77. 10.1016/j.mio.2012.07.002

- Benoit-Bird, K. J., & Lawson, G. L. (2016). Ecological insights from pelagic habitats acquired using active acoustic techniques. Annual Review of Marine Science, 8(1), 463–490. 10.1146/annurev-marine-122414-034001

- Wall, C. C., Jech, J. M., & McLean, S. J. (2016). Increasing the accessibility of acoustic data through global access and imagery. ICES Journal of Marine Science: Journal Du Conseil, 73(8), 2093–2103. 10.1093/icesjms/fsw014

- Klevjer, T. A., Irigoien, X., Røstad, A., Fraile-Nuez, E., Benítez-Barrios, V. M., & Kaartvedt., S. (2016). Large scale patterns in vertical distribution and behaviour of mesopelagic scattering layers. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 19873. 10.1038/srep19873

- Korneliussen, R., Ona, E., Eliassen, I., Heggelund, Y., Patel, R., Godo, O. R., Giertsen, C., Patel, D., Nornes, E., Bekkvik, T., Knudsen, H. P., & Lien, G. (2006). The Large Scale Survey System - LSSS. Proceedings of the 29th Scandinavian Symposium on Physical Acoustics. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:204802910

- Perrot, Y., Brehmer, P., Habasque, J., Roudaut, G., Behagle, N., Sarré, A., & Lebourges-Dhaussy, A. (2018). Matecho: An Open-Source Tool for Processing Fisheries Acoustics Data. Acoustics Australia, 46(2), 241–248. 10.1007/s40857-018-0135-x

- Ladroit, Y., Escobar-Flores, P. C., Schimel, A. C. G., & O’Driscoll, R. L. (2020). ESP3: An open-source software for the quantitative processing of hydro-acoustic data. SoftwareX, 12, 100581. 10.1016/j.softx.2020.100581

- Bednar, J. A., & Durant, M. (2023). The Pandata Scalable Open-Source Analysis Stack. Proceedings of the 22nd Python in Science Conference, 85–92. 10.25080/gerudo-f2bc6f59-00b

- Haris, K., Kloser, R. J., Ryan, T. E., Downie, R. A., Keith, G., & Nau, A. W. (2021). Sounding out life in the deep using acoustic data from ships of opportunity. Scientific Data, 8(1), 23. 10.1038/s41597-020-00785-8

- Trowbridge, J., Weller, R., Kelley, D., Dever, E., Plueddemann, A., Barth, J. A., & Kawka, O. (2019). The Ocean Observatories Initiative. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6. 10.3389/fmars.2019.00074

- Moline, M. A., Benoit-Bird, K., O’Gorman, D., & Robbins, I. C. (2015). Integration of scientific echo sounders with an adaptable autonomous vehicle to extend our understanding of animals from the surface to the bathypelagic. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 32(11), 2173–2186. 10.1175/JTECH-D-15-0035.1

- Brautaset, O., Waldeland, A. U., Johnsen, E., Malde, K., Eikvil, L., Salberg, A.-B., & Handegard, N. O. (2020). Acoustic classification in multifrequency echosounder data using deep convolutional neural networks. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 77(4), 1391–1400. 10.1093/ICESJMS/FSZ235

- Choi, C., Kampffmeyer, M., Handegard, N. O., Salberg, A.-B., & Jenssen, R. (2023). Deep semisupervised semantic segmentation in multifrequency echosounder data. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering, 1–17. 10.1109/JOE.2022.3226214

- Urmy, S. S., De Robertis, A., & Bassett, C. (2023). A Bayesian inverse approach to identify and quantify organisms from fisheries acoustic data. ICES Journal of Marine Science, fsad102. 10.1093/icesjms/fsad102