Galyleo: A General-Purpose Extensible Visualization Solution

Abstract¶

Galyleo is an open-source, extensible dashboarding solution integrated with JupyterLab JupyterLab documentation, n.d.. Galyleo is a standalone web application integrated as an iframe Lawson & Sharp, 2010 into a JupyterLab tab. Users generate data for the dashboard inside a Jupyter Notebook Kluyver et al., 2016, which transmits the data through message passing Window.postMessage() - web apis: MDN, n.d. to the dashboard; users use drag-and-drop operations to add widgets to filter, and charts to display the data, shapes, text, and images. The dashboard is saved as a JSON Crockford, 2006 file in the user’s filesystem in the same directory as the Notebook.

Introduction¶

Current dashboarding solutions High-level tools to simplify visualization in Python, 2022Installation - Holoviews v1.14.9, 2022Dash overview, n.d.Panel, 2022 for Jupyter either involve external, heavyweight tools, ingrained HTML/CSS coding, complex publication, or limited control over layout, and have restricted widget sets and visualization libraries. Graphics objects require a great deal of configuration: size, position, colors, fonts must be specified for each object. Thus library solutions involve a significant amount of fairly simple code. Conversely, visualization involves analytics, an inherently complex set of operations. Visualization tools such as Tableau D'Agostino et al., 2013 or Looker Looker, n.d. combine visualization and analytics in a single application presented through a point-and-click interface. Point-and-click interfaces are limited in the number and complexity of operations supported. The complexity of an operation isn’t reduced by having a simple point-and-click interface; instead, the user is confronted with the challenge of trying to do something complicated by pointing. The result is that tools encapsulate complex operations in a few buttons, and that leads to a limited number of operations with reduced options and/or tools with steep learning curves.

In contrast, Jupyter is simply a superior analytics environment in every respect over a standalone visualization tool: its various kernels and their libraries provide a much broader range of analytics capabilities; its programming interface is a much cleaner and simpler way to perform complex operations; hardware resources can scale far more easily than they can for a visualization tool; and connectors to data sources are both plentiful and extensible.

Both standalone visualization tools and Jupyter libraries have a limited set of visualizations. Jupyter is a server-side platform. Jupyter’s web interface is primarily to offer textboxes for code entry. Entered code is sent to the server for evaluation and text/HTML results returned. Visualization in a Jupyter Notebook is either given by images rendered server-side and returned as inline image tags, or by JavaScript/HTML5 libraries which have a corresponding server-side Python library. The Python library generates HTML5/JavaScript code for rendering.

The limiting factor is that the visualization library must be integrated with the Python backend by a developer, and only a subset of the rich array of visualization, charting, and mapping libraries available on the HTML5/JavaScript platform is integrated. The HTML5/JavaScript platform is as rich a client-side visualization platform as Python is a server-side platform.

Galyleo set out to offer the best of both worlds: Python, R, and Julia as a scalable analytics platform coupled with an extensible JavaScript/HTML5 visualization and interaction platform. It offers a no-code client-side environment, for several reasons.

- The Jupyter analytics community is comfortable with server-side analytics environments (the 100+ kernels available in Jupyter, including Python, R and Julia) but less so with the JavaScript visualization platform.

- Configuration of graphical objects takes a lot of low-value configuration code; conversely, it is relatively easy to do by hand.

These insights lead to a mixed interface, combining a drag-and-drop interface for the design and configuration of visual objects, and a coding, server-side interface for analytics programs.

Extension of the widget set was an important consideration. A widget is a client-side object with a physical component. Galyleo is designed to be extensible both by adding new visualization libraries and components and by adding new widgets.

Publication of interactive dashboards has been a further challenge. A design goal of Galyleo was to offer a simple scheme, where a dashboard could be published to the web with a single click.

These then, are the goals of Galyleo:

- Simple, drag-and-drop design of interactive dashboards in a visual editor. The visual design of a Galyleo dashboard should be no more complex than design of a PowerPoint or Google slide;

- Radically simplify the dashboard-design interface by coupling it to a powerful, Jupyter back end to do the analytics work, separating visualization and analytics concerns;

- Maximimize extensibility for visualization and widgets on the client side and analytics libraries, data sources and hardware resources on the server side;

- Easy, simple publication;

Using Galyleo¶

The general usage model of Galyleo is that a Notebook is being edited and executed in one tab of JupyterLab, and a corresponding dashboard file is being edited and executed in another; as the Notebook executes, it uses the Galyleo Client library to send data to the dashboard file. To JupyterLab, the Galyleo Dashboard Studio is just another editor; it reads and writes .gd.json files in the current directory.

The Dashboard Studio¶

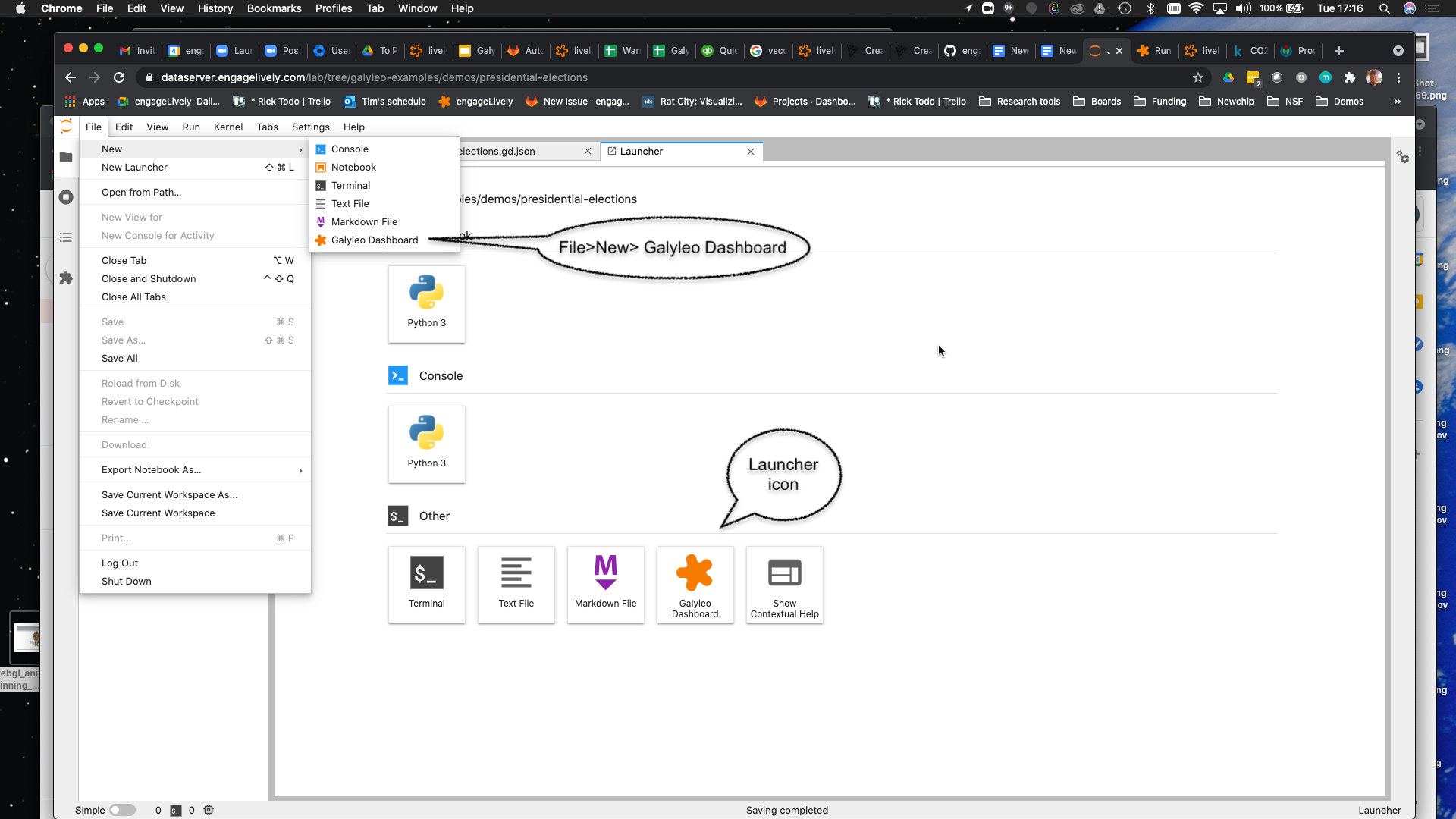

A new Galyleo Dashboard can be launched from the JupyterLab launcher or from the File>New menu, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:A New Galyleo Dashboard

An existing dashboard is saved as a .gd.json file, and is denoted with the Galyleo star logo. It can be opened in the usual way, with a double-click.

Once a file is opened, or a new file created, a new Galyleo tab opens onto it. It resembles a simplified form of a Tableau, Looker, or PowerBI editor. The collapsible right-hand sidebar offers the ability to view Tables, and view, edit, or create Views, Filters, and Charts. The bottom half of the right sidebar gives controls for styling of text and shapes.

Figure 2:The Galyleo Dashboard Studio

The top bar handles the introduction of decorative and styling elements to the dashboard: labels and text, simple shapes such as ellipses, rectangles, polygons, lines, and images. All images are referenced by URL.

As the user creates and manipulates the visual elements, the editor continuously saves the table as a JSON file, which can also be edited with Jupyter’s built-in text editor.

Workflow¶

The goal of Galyleo is simplicity and transparency. Data preparation is handled in Jupyter, and the basic abstract item, the GalyleoTable is generally created and manipulated there, using an open-source Python library. When a table is ready, the GalyleoClient library is invoked to send it to the dashboard, where it appears in the table tab of the sidebar. The dashboard author then creates visual elements such as sliders, lists, dropdowns etc., which select rows of the table, and uses these filtered lists as inputs to charts. The general idea is that the author should be able to seamlessly move between manipulating and creating data tables in the Notebook, and filtering and visualizing them in the dashboard.

Data Flow and Conceptual Picture¶

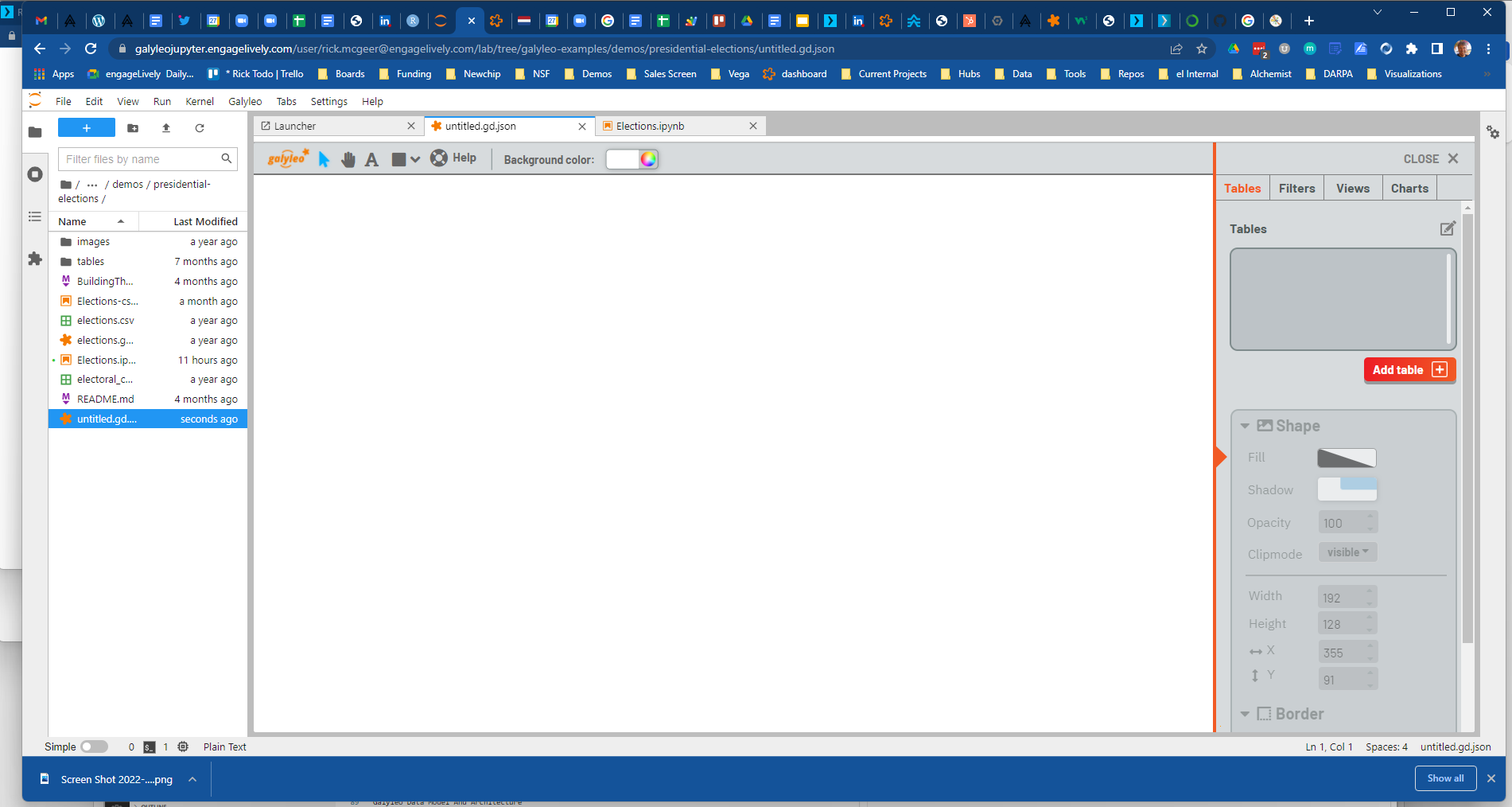

The Galyleo Data Model and Architecture is discussed in detail below. The central idea is to have a few, orthogonal, easily-grasped concepts which make data manipulation easy and intuitive. The basic concepts are as follows:

- Table: A Table is a list of records, equivalent to a Pandas DataFrame The pandas development team, 2020McKinney, 2010 or a SQL Table. In general, in Galyleo, a Table is expected to be produced by an external source, generally a Jupyter Notebook

- Filter: A Filter is a logical function which applies to a single column of a Table Table, and selects rows from the Table. Each Filter corresponds to a widget; widgets set the values Filter use to select Table rows

- View A View is a subset of a Table selected by one or more Filters. To create a view, the user chooses a Table, and then chooses one or more Tilters to apply to the Table to select the rows for the View. The user can also statically select a subset of the columns to include in the View.

- Chart A Chart is a generic term for an object that displays data graphically. Its input is a View or a Table. Each Chart has a single data source.

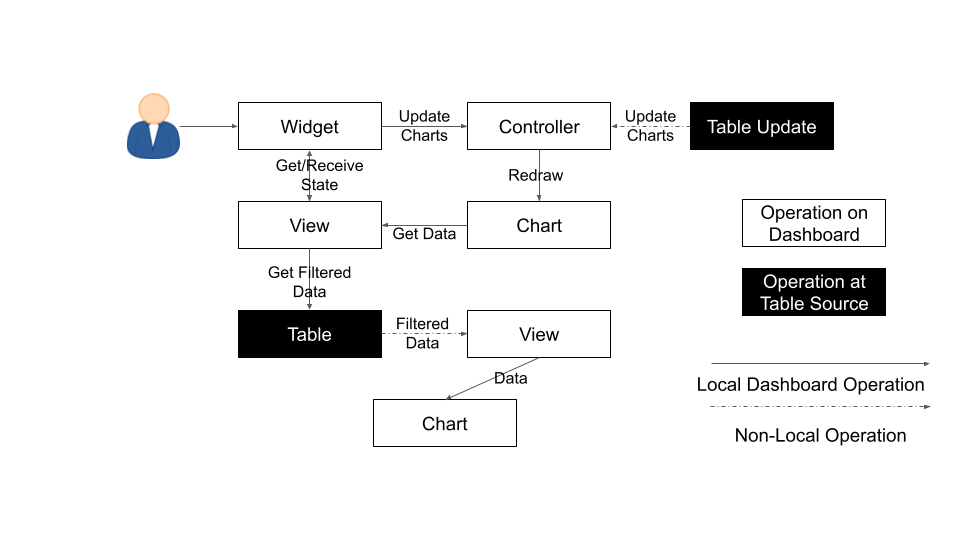

Figure 3:Dataflow in Galyleo

The data flow is straightforward. A Table is updated from an external source, or the user manipulates a widget. When this happens, the affected item signals the dashboard controller that it has been updated. The controller then signals all charts to redraw themselves. Each Chart will then request updated data from its source Table or View. A View then requests its configured filters for their current logic functions, and passes these to the source Table with a request to apply the filters and return the rows which are selected by all the filters (in the future, a more general Boolean will be applied; the UI elements to construct this function are under design). The Table then returns the rows which pass the filters; the View selects the static subset of columns it supports, and passes this to its Charts, which then redraw themselves.

Each item in this flow conceptually has a single data source, but multiple data targets. There can be multiple Views over a Table, but each View has a single Table as a source. There can be multiple charts fed by a View, but each Chart has a single Table or View as a source.

It’s important to note that there are no special cases. There is no distinction, as there is in most visualization systems, between a “Dimension” or a “Measure”; there are simply columns of data, which can be either a value or category axis for any Chart. From this simplicity, significant generality is achieved. For example, a filter selects values from any column, whether that column is providing value or category. Applying a range filter to a category column gives natural telescoping and zooming on the x-axis of a chart, without change to the architecture.

Drilldowns¶

An important operation for any interactive dashboard is drilldowns: expanding detail for a datapoint on a chart. The user should be able to click on a chart and see a detailed view of the data underlying the datapoint. This was naturally implemented in our system by associating a filter with every chart: every chart in Galyleo is also a Select Filter, and it can be used as a Filter in a view, just as any other widget can be.

Publishing The Dashboard¶

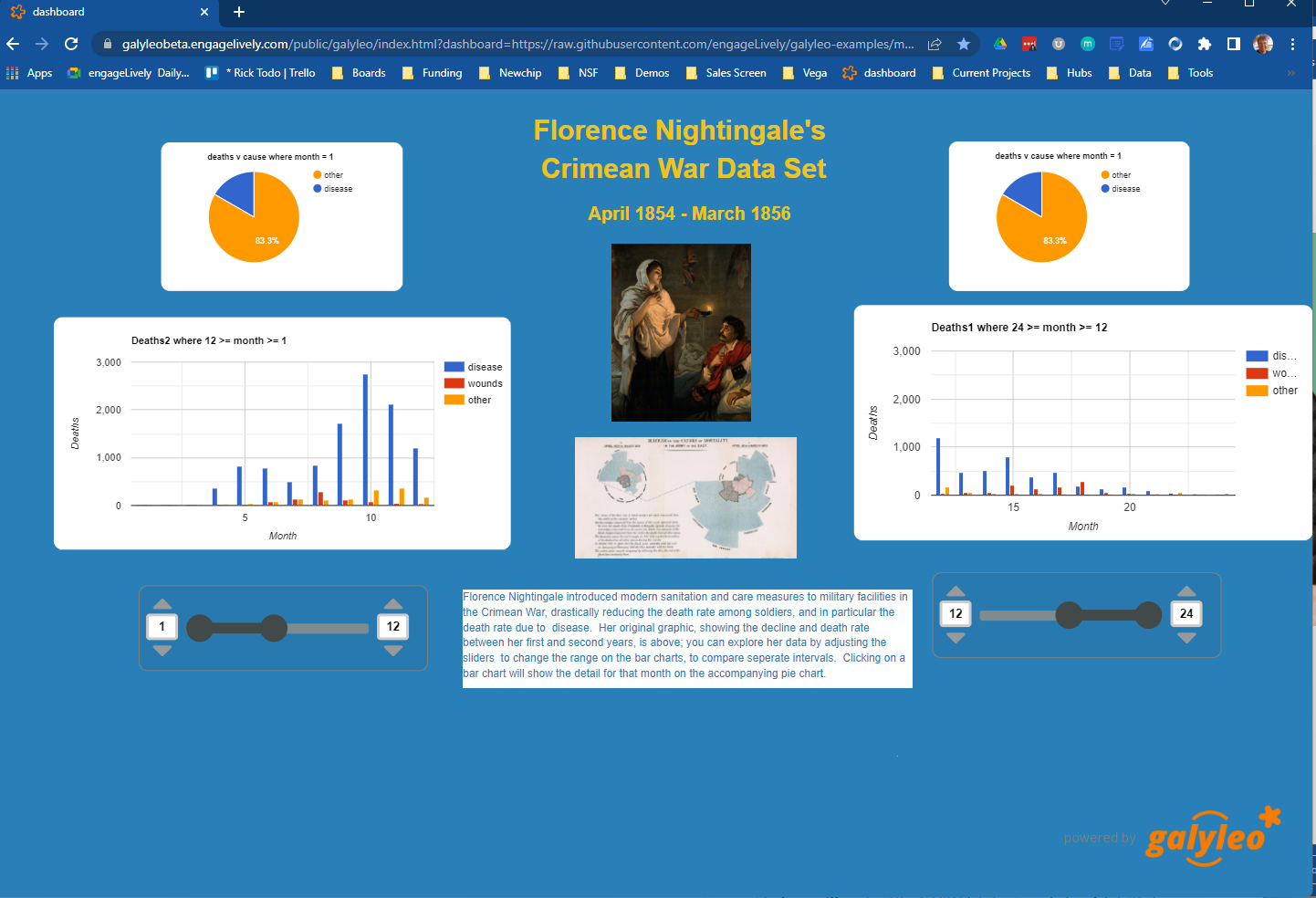

Once the dashboard is complete, it can be published to the web simply by moving the dashboard file to any place it get an URL (e.g. a github repo). It can then be viewed by visiting https://galyleobeta.engagelively.com/public/galyleo/index.html?dashboard=<url of dashboard file>. Figure 4 shows a published Galyleo Dashboard, which displays Florence Nightingale’s famous Crimean War dataset. Using the double sliders underneath the column charts telescope the x axes, effectively permitting zooming on a range; clicking on a column shows the detailed death statistics for that month in the pie chart above the column chart.

Figure 4:A Published Galyleo Dashboard

No-Code, Low-Code, and Appropriate-Code¶

Galyleo is an appropriate-code environment, meaning that it offers efficient creation to developers at every step. It offers What-You-See-Is-What-You-Get (WYSIWYG) design tools where appropriate, low-code where appropriate, and full code creation tools where appropriate.

No-code and low-code environments, where users construct applications through a visual interface, are popular for several reasons. The first is the assumption that coding is time-consuming and hard, which isn’t always or necessarily true; the second is the assumption that coding is a skill known to only a small fraction of the population, which is becoming less true by the day. 40% of Berkeley undergraduates take Data 8, in which every assignment involves programming in a Jupyter Notebook. The third, particularly for graphics code, is that manual design and configuration gives instant feedback and tight control over appearance. For example, the authors of a LaTeX paper (including this one) can’t control the placement of figures within the text. The fourth, which is correct, is that configuration code is more verbose, error-prone, and time-consuming than manual configuration.

What is less often appreciated is that when operations become sufficiently complex, coding is a much simpler interface than manual configuration. For example, building a pivot table in a spreadsheet using point-and-click operations have “always had a reputation for being complicated” Devaney, n.d.. It’s three lines of code in Python, even without using the Pandas pivot_table method. Most analytics procedures are far more easily done in code.

As a result, Galyleo is an appropriate-code environment, which is an environment which combines a coding interface for complex, large-scale, or abstract operations and a point-and-click interface for simple, concrete, small-scale operations. Galyleo combines broadly powerful Jupyter-based code and low-code libraries for analytics paired with fast GUI-based design and configuration for graphical elements and layout.

Galyleo Data Model And Architecture¶

The Galyleo data Model and architecture closely model the dashboard architecture discussed in the previous section. They are based on the idea of a few simple, generalizable structures, which are largely independent of each other and communicate through simple interfaces.

The GalyleoTable¶

A GalyleoTable is the fundamental data structure in Galyleo. It is a logical, not a physical abstraction; it simply responds to the GalyleoTable API. A GalyleoTable is a pair (columns, rows), where columns is a list of pairs (name, type), where type is one of {string, boolean, number, date}, and rows is a list of lists of primitive values, where the length of each component list is the length of the list of columns and the type of the kth entry in each list is the type specified by the kth column.

Small, public tables may be contained in the dashboard file; these are called explicit tables. However, explicitly representing the table in the dashboard file has a number of disadvantages:

- An explicit table is in the memory of the client viewing the dashboard; if it is too large, it may cause significant performance problems on the dashboard author or viewer’s device

- Since the dashboard file is accessible on the web, any data within it is public

- The data may be continuously updated from a source, and it’s inconvenient to re-run the Notebook to update the data.

Therefore, the GalyleoTable can be of one of three types:

- A data server that implements the Table REST API

- A JavaScript object within the dashboard page itself

- A JavaScript messenger in the page that implements a messaging version of the API

An explicit table is simply a special case of (2) -- in this case, the JavaScript object is simply a linear list of rows.

These are not exclusive. The JavaScript messenger case is designed to support the ability of a containing application within the browser to handle viewer authentication, shrinking the security vulnerability footprint and ensuring that the client application controls the data going to the dashboard. In general, aside from performing tasks like authentication, the messenger will call an external data server for the values themselves.

Whether in a Data Server, a containing application, or a JavaScript object, Tables support three operations:

- Get all the values for a specific column

- Get the max/min/increment for a specific numeric column

- Get the rows which match a boolean function, passed in as a parameter to the operation

Of course, (3) is the operation that we have seen above, to populate a view and a chart. (1) and (2) populate widgets on the dashboard; (1) is designed for a select filter, which is a widget that lets a user pick a specific set of values for a column; (2) is an optimization for numeric filters, so that the entire list of values for the column need not be sent -- rather, only the start and end values, and the increment between them.

Each type of table specifies a source, additional information (in the case of a data server, for example, any header variables that must be specified in order to fetch the data), and, optionally, a polling interval. The latter is designed to handle live data; the dashboard will query the data source at each polling interval to see if the data has changed.

The choice of these three table instantiations (REST, JavaScript object, messenger) is that they provide the key foundational building block for future extensions; it’s easy to add a SQL connection on top of a REST interface, or a Python simulator.

Filters¶

Tables must be filtered in situ. One of the key motivators behind remote tables is in keeping large amounts of data from hitting the browser. This is largely defeated if the entire table is sent to the dashboard and then filtered there. As a result, there is a Filter API together with the Table API wherever there are tables.

The data flow of the previous section remains unchanged; it is simply that the filter functions are transmitted to wherever the tables happen to be. The dataflow in the case of remote tables (whether messenger-based or REST-based) is shown here, with operations that are resident where the table is situated and operations resident on the dashboard clearly shown.

Figure 5:Galyleo Dataflow with Remote Tables

Comments¶

Again, simplicity and orthogonality have shown tremendous benefits here. Though filters conceptually act as selectors on rows, they may perform a variety of roles in implementations. For example, a table produced by a simulator may be controlled by a parameter value given by a Filter function.

Extending Galyleo¶

Every element of the Galyleo system, whether it is a widget, Chart, Table Server, or Filter is defined exclusively through a small set of public APIs. This is done to permit easy extension, by either the Galyleo team, users, or third parties. A Chart is defined as an object which has a physical HTML representation, and it supports four JavaScript methods: redraw (draw the chart), set data (set the chart’s data), set options (set the chart’s options), and supports table (a boolean which returns true if and only if the chart can draw the passed-in data set). In addition, it exports out a defined JSON structure which indicates what options it supports and the types of their values; this is used by the Chart Editor to display a configurator for the chart.

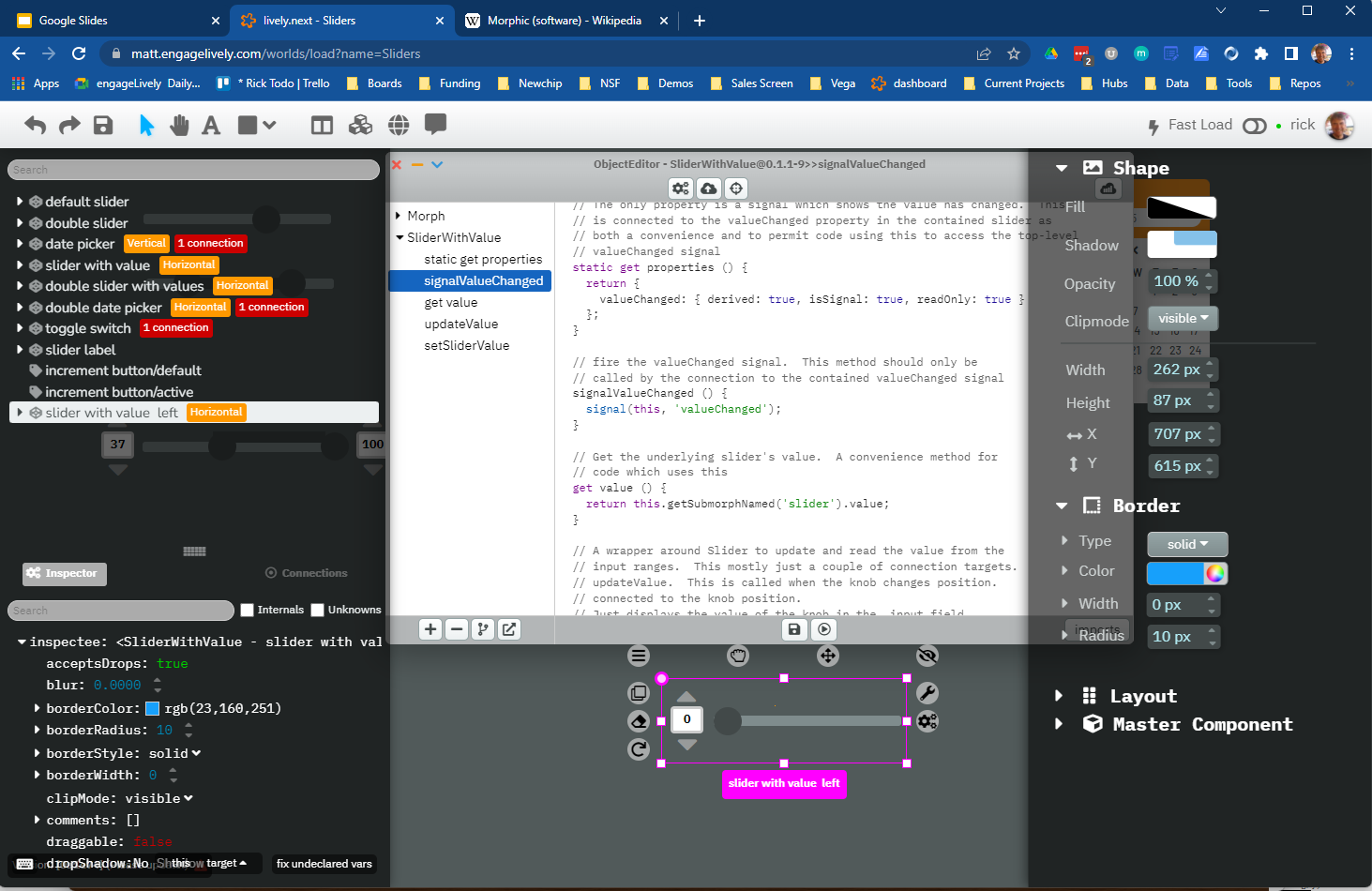

Similarly, the underlying lively.next system supports user design of new filters. Again, a filter is simply an object with a physical presence, that the user can design in lively, and supports a specific API -- broadly, set the choices and hand back the Boolean function as a JSON object which will be used to filter the data.

lively.next¶

Any system can be used to extend Galyleo; at the end of the day, all that need be done is encapsulate a widget or chart in a snippet of HTML with a JavaScript interface that matches the Galyleo protocol. This is done most easily and quickly by using lively.next Schrieber et al., 2021. lively.next is the latest in a line of Smalltalk- and Squeak-inspired Ingalls et al., 1997 JavaScript/HTML integrated development environments that began with the Lively Kernel Ingalls et al., 2008Krahn et al., 2009 and continued through the Lively Web Lincke et al., 2012Ingalls et al., 2016Taivalsaari & Mikkonen, 2017. Galyleo is an application built in Lively, following the work done in Hemmings et al. (2016).

Lively shares with Jupyter an emphasis on live programming Kubelka et al., 2018, or where a Read-Evaluate-Act Loop (REAL) programming style. It adds to that a combination of visual and text programming Andersen et al., 2020, where physical objects are positioned and configured largely by hand as done with any drawing or design program (e.g., PowerPoint, Illustrator, DrawPad, Google Draw) and programmed with a built-in editor and workspace, similar in concept if not form to a Jupyter Notebook.

Lively abstracts away HTML and CSS tags in graphical objects called “Morphs”. Morphs Maloney & Smith, 1995 were invented as the user interface layer for Self Ungar & Smith, 1987, and have been used as the foundation of the graphics system in Squeak and Scratch Maloney et al., 2010. In this UI, every physical object is a Morph; these can be as simple as a simple polygon or text string to a full application. Morphs are combined via composition, similar to the way that objects are grouped in a presentation or drawing program. The composition is simply another Morph, which in turn can be composed with other Morphs. In this manner, complex Morphs can be built up from collections of simpler ones. For example, a slider is simply the composition of a circle (the knob) with a thin, long rectangle (the bar). Each Morph can be individually programmed as a JavaScript object, or can inherit base level behavior and extend it.

Figure 6:The lively.next environment

In lively.next, each morph turns into a snippet of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript code and the entire application turns into a web page. The programmer doesn’t see the HTML and CSS code directly; these are auto-generated. Instead, the programmer writes JavaScript code for both logic and configuration (to the extent that the configuration isn’t done by hand). The code is bundled with the object and integrated in the web page.

Morphs can be set as reusable components by a simple declaration. They can then be reused in any lively design.

Incorporating New Libraries¶

Libraries are typically incorporated into lively.next by attaching them to a convenient physical object, importing the library from a package manager such as npm, and then writing a small amount of code to expose the object’s API. The simplest form of this is to assign the module to an instance variable so it has an addressable name, but typically a few convenience methods are written as well. In this way, a large number of libraries have been incorporated as reusable components in lively.next, including Google Maps, Google Charts Google, n.d., Chartjs Chart.js, n.d., D3 Bostock et al., 2011, Leaflet.js An open-source JavaScript library for interactive maps, n.d., OpenLayers OpenLayers, n.d., cytoscape:ono and many more.

Extending Galyleo’s Charting and Visualization capabilities¶

A Galyleo Chart is anything that changes its display based on tabular data from a Galyleo Table or Galyleo View. It responds to a specific API, which includes two principal methods:

drawChart: redraw the chart using the current tabular data from the input or viewacceptsDataset(<Table or View>)returns a boolean depending on whether this chart can draw the data in this view. For example, a Table Chart can draw any tabular data; a Geo Chart typically requires that the first column be a place specifier.

In addition, it has a read-only property:

optionSpec: A JSON structure describing the options for the chart. This is a dictionary, which specifies the name of each option, and its type (color, number, string, boolean, or enum with values given). Each type corresponds to a specific UI widget that the chart editor uses.

And two read write properties:

options: The current options, as a JSON dictionary. This matches exactly the JSON dictionary inoptionSpec, with values in place of the types.dataSource: a string, the name of the current Galyleo Table or Galyleo View

Typically, an extension to Galyleo’s charting capabilities is done by incorporating the library as described in the previous section, implementing the API given in this section, and then publishing the result as a component

Extending Galyleo’s Widget Set¶

A widget is a graphical item used to filter data. It operates on a single column on any table in the current data set. It is either a range filter (which selects a range of numeric values) or a select filter (which selects a specific value, or a set of specific values). The API that is implemented consists only of properties.

valueChanged: a signal, which is fired whenever the value of the widget is changedvalue: read-write. The current value of the widgetfilter: read-only. The current filter function, as a JSON structureallValues: read-write, select filters only.column: read-only. The name of the column of this widget. Set when the widget is creatednumericSpec: read-write. A dictionary containing the numeric specification for a numeric or date filter

Widgets are typically designed as a standard Lively graphical component, much as the slider described above.

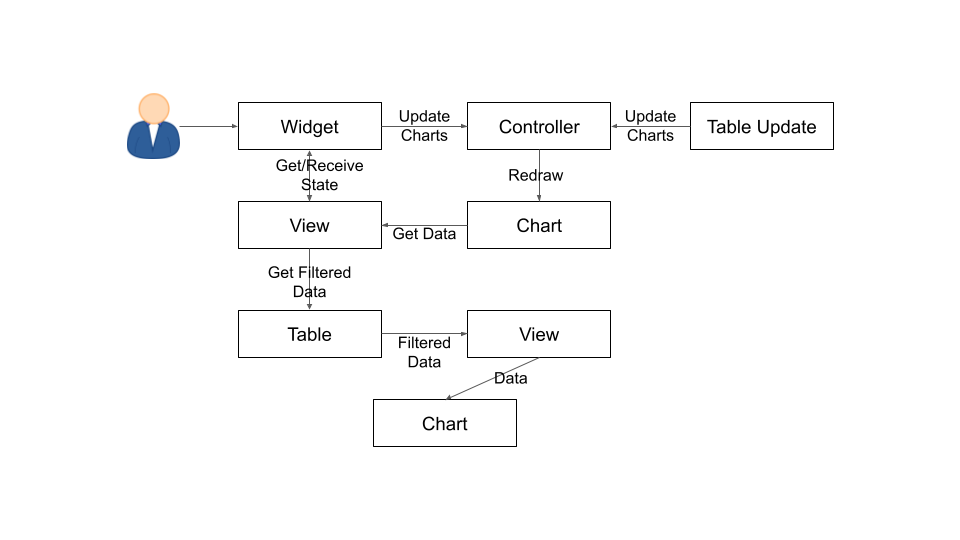

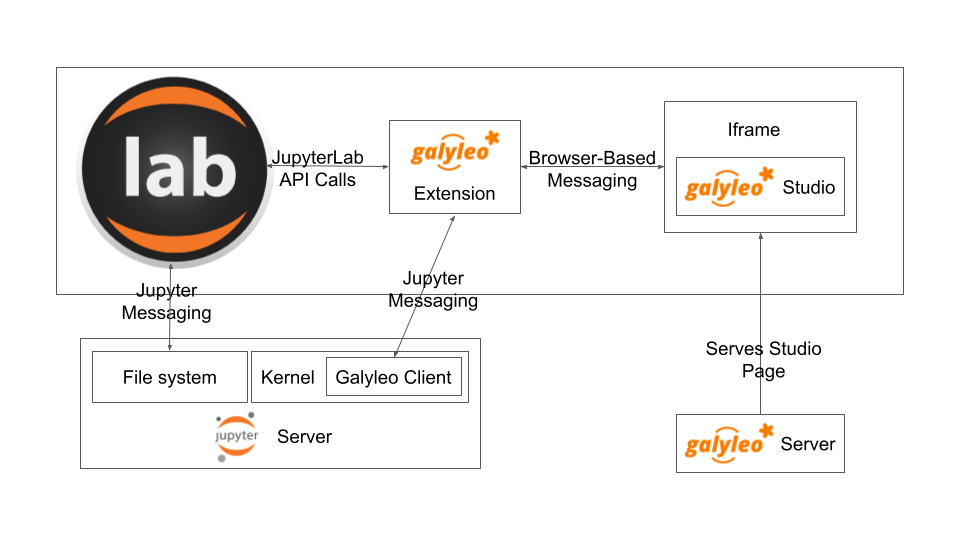

Integration into Jupyter Lab: The Galyleo Extension¶

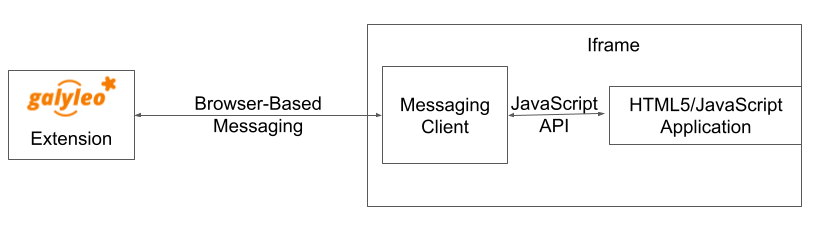

Galyleo is a standalone web application that is integrated into JupyterLab using an iframe inside a JupyterLab tab for physical design. A small JupyterLab extension was built that implements the JupyterLab editor API. The JupyterLab extension has two major functions: to handle read/write/undo requests from the JupyterLab menus and file browser, and receive and transmit messages from the running Jupyter kernels to update tables on the Dashboard Studio, and to handle the reverse messages where the studio requests data from the kernel.

Figure 7:Galyleo Extension Architecture

Standard Jupyter and browser mechanisms are used. File system requests come to the extension from the standard Jupyter API, exactly the same requests and mechanisms that are sent to a Markdown or Notebook editor. The extension receives them, and then uses standard browser-based messaging (window.postMessage) to signal the standalone web app. Similarly, when the extension makes a request of JupyterLab, it does so through this mechanism and a receiver in the extension gets it and makes the appropriate method calls within JupyterLab to achieve the objective.

When a kernel makes a request through the Galyleo Client, this is handled exactly the same way. A Jupyter messaging server within the extension receives the message from the kernel, and then uses browser messaging to contact the application with the request, and does the reverse on a Galyleo message to the kernel.

This is a highly efficient method of interaction, since browser-based messaging is in-memory transactions on the client machine.

It’s important to note that there is nothing Galyleo-specific about the extension: the Galyleo Extension is a general method for any standalone web editor (e.g., a slide or drawing editor) to be integrated into JupyterLab. The JupyterLab connection is a few tens of lines of code in the Galyleo Dashboard. The extension is slightly more complex, but it can be configured for a different application with a simple data structure which specifies the URL of the application, file type and extension to be manipulated, and message list.

The Jupyter Computer¶

The implications of the Galyleo Extension go well beyond visualization and dashboards and easy publication in JupyterLab. JupyterLab is billed as the next-generation integrated Development Environment for Jupyter, but in fact it is substantially more than that. It is the user interface and windowing system for Cloud-based personal computing. Inspired by previous extensions such as the Vega Extension, the Galyleo Extensions seeks to provide the final piece of the puzzle.

Consider a Jupyter server in the Cloud, served from a JupyterHub such as the Berkeley Data Hub. It’s built from a base Ubuntu image, with the standard Jupyter libraries installed and, importantly, a UI that includes a Linux terminal interface. Any Linux executable can be installed in the Jupyter server image, as can any Jupyter kernel, and any collection of libraries. The Jupyter server has per-user persistent storage, which is organized in a standard Linux filesystem. This makes the Jupyter server a curated execution environment with a Linux command-line interface and a Notebook interface for Jupyter execution.

A JupyterHub similar to Berkeley Data Hub (essentially, anything built from Zero 2 Jupyter Hub or Q-Hub) comes with a number of “environments”. The user chooses the environment on startup. Each environment comes with a built-in set of libraries and executables designed for a specific task or set of tasks. The number of environments hosted by a server is arbitrary, and the cost is only the cost of maintaining the Dockerfile for each environment.

An environment is easy to design for a specific class, project, or task; it’s simply adding libraries and executables to a base Dockerfile. It must be tested, of course, but everything must be. And once it is tested, the burden of software maintenance and installation is removed from the user; the user is already in a task-customized, curated environment. Of course, the usual installation tools (apt, pip, conda, easy_install) can be pre-loaded (they’re just executables) so if the environment designer missed something it can be added by the end user.

Though a user can only be in one environment at a time, persistent storage is shared across all environments, meaning switching environments is simply a question of swapping one environment out and starting another.

Viewed in this light, a JupyterHub is a multi-purpose computer in the Cloud, with an easy-to-use UI that presents through a browser. JupyterLab isn’t simply an IDE; it’s the window system and user interface for this computer. The JupyterLab launcher is the desktop for this computer (and it changes what’s presented, depending on the environment); the file browser is the computer’s file browser, and the JupyterLab API is the equivalent of the Windows or MacOS desktop APIs and window system that permits third parties to build applications for this.

This Jupyter Computer has a large number of advantages over a standard desktop or laptop computer. It can be accessed from any device, anywhere on Earth with an Internet connection. Software installation and maintenance issues are nonexistent. Data loss due to hardware failure is extremely unlikely; backups are still required to prevent accidental data loss (e.g., erroneous file deletion), but they are far easier to do in a Cloud environment. Hardware resources such as disk, RAM, and CPU can be added rapidly, on a permanent or temporary basis. Relatively exotic resources (e.g., GPUs) can also be added, again on an on-demand, temporary basis.

The advantages go still further than that. Any resource that can be accessed over a network connection can be added to the Jupyter Computer simply by adding the appropriate accessor library to an environment’s Dockerfile. For example, a database solution such as Snowflake, BigQuery, or Amazon Aurora (or one of many others) can be “installed” by adding the relevant library module to the environment. Of course, the user will need to order the database service from the relevant provider, and obtain authentication tokens, and so on -- but this is far less troublesome than even maintaining the library on the desktop.

However, to date the Jupyter Computer only supports a few window-based applications, and adding a new application is a time-consuming development task. The applications supported are familiar and easy to enumerate: a Notebook editor, of course; a Markdown Viewer; a CSV Viewer; a JSON Viewer (not inline editor), and a text editor that is generally used for everything from Python files to Markdown to CSV.

This is a small subset of the rich range of JavaScript/HTML5 applications which have significant value for Jupyter Computer users. For example, the Ace Code Editor supports over 110 languages and has the functionality of popular desktop editors such as Vim and Sublime Text. There are over 1100 open-source drawing applications on the JavaScript/HTML5 platform; multiple spreadsheet applications, the most notable being jExcel, and many more.

Up until now, adding a new application to JupyterLab involved writing a hand-coded extension in Typescript, and compiling it into JupyterLab. However, the Galyleo Extension has been designed so that any HTML5/JavaScript application can be added easily, simply by configuring the Galyleo Extension with a small JSON file.

The promise of the Galyleo Extension is that it can be adapted to any open-source JavaScript/HTML5 application very easily. The Galyleo Extension merely needs the:

- URL of the application

- File extension that the application reads/writes

- URL of an image for the launcher

- Name of the application for the file menu

The application must implement a small messaging client, using the standard JavaScript messaging interface, and implement the calls the Galyleo Extension makes. The conceptual picture is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8:Galyleo Extension Application-Side messaging

And it must support (at a minimum) messages to read and write the file being edited.

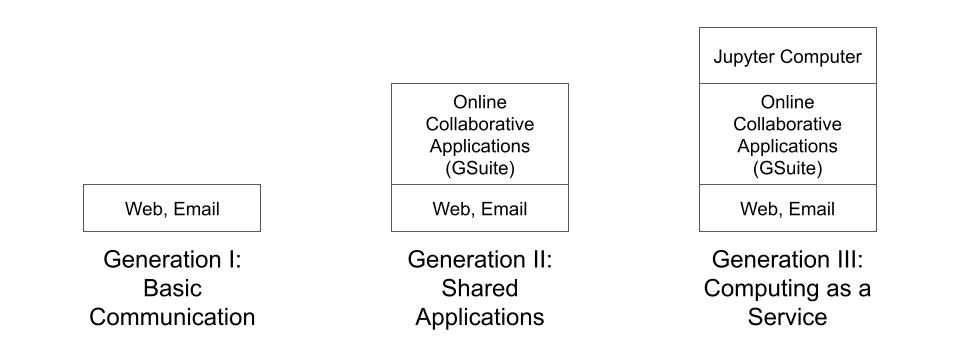

The Third Generation of Network Computing¶

The World-Wide Web and email comprised the first generation of Internet computing (the Internet had been around for a decade before the Web, and earlier networks dated from the sixties, but the Web and email were the first mass-market applications on the network), and they were very simple -- both were document-exchange applications, using slightly different protocols. The second generation of Network applications were the siloed productivity applications, where standard desktop applications moved to the Cloud. The most famous example is of course GSuite and Office 365, but there were and are many others -- Canva, Loom, Picasa, as well as a large number of social/chat/social media applications. What they all had in common was that they were siloed applications which, with the exception of the office suites, didn’t even share a common store. In many ways, this second generation of network applications recapitulates the era immediately prior to the introduction of the personal computer. That era was dominated by single-application computers such as word processors, which were simply computers with a hardcoded program loaded into ROM.

Figure 9:Generations of Internet Computing

The Word Processor era was due to technological limitations -- the processing power and memory to run multiple programs simply wasn’t available on low-end hardware, and PC operating systems didn’t yet exist. In some sense, the current second generation of Internet Computing suffers from similar technological constraints. The “Operating System” for Internet Computing doesn’t yet exist. The Jupyter Computer can provide it.

To see the difference that this can make, consider LaTeX (perhaps preceded by Docutils, as is the case for SciPy) preparation of a document. On a personal computer, it’s fairly straightforward; the user uses any of a wide variety of text editors to prepare the document, any of a wide variety of productivity and illustrator programs to prepare the images, runs this through a local sequence of commands (e.g., pdflatex paper; bibtex paper; pdflatex paper). Usually Github or another repository is used for storage and collaboration.

In a Cloud service, this is another matter. There is at most one editor, selected by the service, on the site. There is no image editing or illustrator program that reads and writes files on the site. Auxiliary tools, such as a bib searcher, aren’t present or aren’t customizable. The service has its own siloed storage, its own text editor, and its own document-preparation pipeline. The tools (aside from the core document-preparation program) are primitive. The online service has two advantages over the personal-device service. Collaboration is generally built-in, with multiple people having access to the project, and the software need not be maintained. Aside from that, the personal-device experience is generally superior. In particular, the user is free to pick their own editor, and doesn’t have to orchestrate multiple downloads and uploads from various websites. The usual collection of command-line utilities are available to small touchups.

The third generation of Internet Computing represented by the Jupyter Computer. This offers a Cloud experience similar to the personal computer, but with the scalability, reliability, and ease of collaboration of the Cloud.

Conclusion and Further Work¶

The vision of the Jupyter Computer, bringing the power of the Cloud to the personal computing experience has been started with Galyleo. It will not end there. At the heart of it is a composition of two broadly popular platforms: HTML5/JavaScript for presentation and interaction, and the various Jupyter kernels for server-side analytics. Galyleo is a start at seamless interaction of these two platforms. Continuing and extending this is further development of narrow-waist protocols to permit maximal independent development and extension.

The authors wish to thank Alex Yang, Diptorup Deb, and for their insightful comments, and Meghann Agarwal for stewardship. We have received invaluable help from Robert Krahn, Marko Röder, Jens Lincke and Linus Hagemann. We thank the engageLively team for all of their support and help: Tim Braman, Patrick Scaglia, Leighton Smith, Sharon Zehavi, Igor Zhukovsky, Deepak Gupta, Steve King, Rick Rasmussen, Patrick McCue, Jeff Wade, Tim Gibson. The JupyterLab development community has been helpful and supportive; we want to thank Tony Fast, Jason Grout, Mehmet Bektas, Isabela Presedo-Floyd, Brian Granger, and Michal Krassowski. The engageLively Technology Advisory Board has helped shape these ideas: Ani Mardurkar, Priya Joseph, David Peterson, Sunil Joshi, Michael Czahor, Isha Oke, Petrus Zwart, Larry Rowe, Glenn Ricart, Sunil Joshi, Antony Ng. We want to thank the people from the AWS team that have helped us tremendously: Matt Vail, Omar Valle, Pat Santora. Galyleo has been dramatically improved with the assistance of our Japanese colleagues at KCT and Pacific Rim Technologies: Yoshio Nakamura, Ted Okasaki, Ryder Saint, Yoshikazu Tokushige, and Naoyuki Shimazaki. Our undestanding of Jupyter in an academic context came from our colleagues and friends at Berkeley, the University of Victoria, and UBC: Shawna Dark, Hausi Müller, Ulrike Stege, James Colliander, Chris Holdgraf, Nitesh Mor. Use of Jupyter in a research context was emphasized by Andrew Weidlea, Eli Dart, Jeff D’Ambrogia. We benefitted enormously from the CITRIS Foundry: Alic Chen, Jing Ge, Peter Minor, Kyle Clark, Julie Sammons, Kira Gardner. The Alchemist Accelerator was central to making this product: Ravi Belani, Arianna Haider, Jasmine Sunga, Mia Scott, Kenn So, Aaron Kalb, Adam Frankl. Kris Singh was a constant source of inspiration and help. Larry Singer gave us tremendous help early on. Vibhu Mittal more than anyone inspired us to pursue this road. Ken Lutz has been a constant sounding board and inspiration, and worked hand-in-hand with us to develop this product. Our early customers and partners have been and continue to be a source of inspiration, support, and experience that is absolutely invaluable: Jonathan Tan, Roger Basu, Jason Koeller, Steve Schwab, Michael Collins, Alefiya Hussain, Geoff Lawler, Jim Chimiak, Fraukë Tillman, Andy Bavier, Andy Milburn, Augustine Bui. All of our customers are really partners, none moreso than the fantastic teams at Tanjo AI and Ultisim: Bjorn Nordwall, Ken Lane, Jay Sanders, Eric Smith, Miguel Matos, Linda Bernard, Kevin Clark, and Richard Boyd. We want to especially thank our investors, who bet on this technology and company.

Copyright © 2022 McGeer et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

- REAL

- Read-Evaluate-Act Loop

- JupyterLab documentation. (n.d.). In JupyterLab Documentation - JupyterLab 3.4.2 documentation. https://jupyterlab.readthedocs.io/en/stable/

- Lawson, B., & Sharp, R. (2010). Introducing HTML5 (1st ed.). New Riders Publishing.

- Kluyver, T., Ragan-Kelley, B., Pérez, F., Granger, B., Bussonnier, M., Frederic, J., Kelley, K., Hamrick, J., Grout, J., Corlay, S., Ivanov, P., Avila, D., Abdalla, S., Willing, C., & development team, J. (2016). Jupyter Notebooks - a publishing format for reproducible computational workflows. In F. Loizides & B. Scmidt (Eds.), Positioning and Power in Academic Publishing: Players, Agents and Agendas (pp. 87–90). IOS Press. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/403913/

- Window.postMessage() - web apis: MDN. (n.d.). In Web APIs | MDN. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Window/postMessage

- Crockford, D. (2006). The application/json Media Type for JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) (RFC No. 4627). RFC Editor. 10.17487/rfc4627

- High-level tools to simplify visualization in Python. (2022). In High-level tools to simplify visualization in Python - HoloViz 0.14.0 documentation. https://holoviz.org/

- Installation - Holoviews v1.14.9. (2022). In Installation - HoloViews v1.14.9. https://holoviews.org/

- Dash overview. (n.d.). In Plotly. https://plotly.com/dash/

- Panel. (2022). In Panel Documentation - Panel v0.13.1. https://panel.holoviz.org/

- D’Agostino, M., Gabbay, D. M., Hähnle, R., & Posegga, J. (2013). Handbook of tableau methods. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Looker. (n.d.). https://looker.com/

- The pandas development team. (2020). pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas (latest) [Computer software]. Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.3509134

- Wes McKinney. (2010). Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Stéfan van der Walt & Jarrod Millman (Eds.), Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (pp. 56–61). 10.25080/Majora-92bf1922-00a

- Devaney, E. (n.d.). How to Create a Pivot Table in Excel: A Step-by-Step Tutorial. hubspot. https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/how-to-create-pivot-table-tutorial-ht

- Schrieber, R., Krahn, R., & Hagemann, L. (2021). lively.next. In GitHub.