Papyri: better documentation for the scientific ecosystem in Jupyter

Abstract¶

We present here the idea behind Papyri, a framework we are developing to provide a better documentation experience for the scientific ecosystem. In particular, we wish to provide a documentation browser (from within Jupyter or other IDEs and Python editors) that gives a unified experience, cross library navigation search and indexing. By decoupling documentation generation from rendering we hope this can help address some of the documentation accessibility concerns, and allow customisation based on users’ preferences.

Introduction¶

Over the past decades, the Python ecosystem has grown rapidly, and one of the last bastion where some of the proprietary competition tools shine is integrated documentation. Indeed, open-source libraries are usually developed in distributed settings that can make it hard to develop coherent and integrated systems.

While a number of tools and documentations exists (and improvements are made everyday), most efforts attempt to build documentation in an isolated way, inherently creating a heterogeneous framework. The consequences are twofolds: (i) it becomes difficult for newcomers to grasp the tools properly, (ii) there is a lack of cohesion and of unified framework due to library authors making their proper choices as well as having to maintain build scripts or services.

Many users, colleagues, and members of the community have been frustrated with the documentation experience in the Python ecosystem. Given a library, who hasn’t struggled to find the “official” website for the documentation? Often, users stumble across an old documentation version that is better ranked in their favorite search engine, and this impacts significantly the learning process of less experienced users.

On users’ local machine, this process is affected by limited documentation rendering. Indeed, while in many Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) the inspector provides some documentation, users do not get access to the narrative, or the full documentation gallery. For Command Line Interface (CLI) users, documentation is often displayed as raw source where no navigation is possible. On the maintainers’ side, the final documentation rendering is less of a priority. Rather, maintainers should aim at making users gain from improvement in the rendering without having to rebuild all the docs.

Conda-Forge Conda-Forge Community, 2015 has shown that concerted efforts can give a much better experience to end-users, and in today’s world where it is ubiquitous to share libraries source on code platforms, perform continuous integration and many other tools, we believe a better documentation framework for many of the libraries of the scientific Python should be available.

Thus, against all advice we received and based on our own experience, we have decided to rebuild an opinionated documentation framework, from scratch, and with minimal dependencies: Papyri. Papyri focuses on building an intermediate documentation representation format, that lets us decouple building, and rendering the docs. This highly simplifies many operations and gives us access to many desired features that were not available up to now.

In what follows, we provide the framework in which Papyri has been created and present its objectives (context and goals), we describe the Papyri features (format, installation, and usage), then present its current implementation. We end this paper with comments on current challenges and future work.

Context and objectives¶

Through out the paper, we will draw several comparisons between documentation building and compiled languages. Also, we will borrow and adapt commonly used terminology. In particular, similarities with “ahead-of-time” (AOT) Ahead-of-time compilation, n.d., “just-in-time”" (JIT) Just-in-time compilation, n.d., intermediate representation (IR) Intermediate representation, n.d., link-time optimization (LTO) Interprocedural optimization, n.d., static vs dynamic linking will be highlighted. This allows us to clarify the presentation of the underlying architecture. However, there is no requirement to be familiar with the above to understand the concepts underneath Papyri. In that context, we wish to discuss documentation building as a process from a source-code meant for a machine to a final output targeting the flesh and blood machine between the keyboard and the chair.

Current tools and limitations¶

In the scientific Python ecosystem, it is well known that Docutils Docutils, n.d.

and Sphinx Sphinx, n.d. are major cornerstones for publishing HTML documentation

for Python. In fact, they are used by all the libraries in this ecosystem. While a few

alternatives exist, most tools and services have some internal knowledge of

Sphinx. For instance, Read the Docs Read the Docs, n.d. provides a specific Sphinx theme

Sphinx RTD Theme, n.d. users can opt-in to, Jupyter-book Jupyter Book, n.d. is built on top of Sphinx, and

MyST parser MyST, n.d. (which is made to allow markdown in documentation)

targets Sphinx as a backend, to name a few. All of the above provide an

“ahead-of-time” documentation compilation and rendering, which is slow and

computationally intensive. When a project needs its specific plugins, extensions

and configurations to properly build (which is almost always the case), it is

relatively difficult to build documentation for a single object (like a single

function, module or class). This makes AOT tools difficult to use for

interactive exploration. One can then consider a JIT approach, as done

for Docrepr Docrepr, n.d. (integrated both in Jupyter and Spyder Spyder, n.d.). However in that case,

interactive documentation lacks inline plots, crosslinks, indexing, search and

many custom directives.

Some of the above limitations are inherent to the design of documentation build tools that were intended for a separate documentation construction. While Sphinx does provide features like intersphinx, link resolutions are done at the documentation building phase. Thus, this is inherently unidirectional, and can break easily. To illustrate this, we consider NumPy Harris et al., 2020 and SciPy Virtanen et al., 2020, two extremely close libraries. In order to obtain proper cross-linked documentation, one is required to perform at least five steps:

- build NumPy documentation

- publish NumPy

object.invfile. - (re)build SciPy documentation using NumPy

obj.invfile. - publish SciPy

object.invfile - (re)build NumPy docs to make use of SciPy’s

obj.inv

Only then can both SciPy’s and NumPy’s documentation refer to each other. As one can expect, cross links break every time a new version of a library is published [1]. Pre-produced HTML in IDEs and other tools are then prone to error and difficult to maintain. This also raises security issues: some institutions become reluctant to use tools like Docrepr or viewing pre-produced HTML.

Docstrings format¶

The Numpydoc format is ubiquitous among the scientific ecosystem Numpydoc, n.d.. It is loosely based on reStructuredText (RST) syntax, and despite supporting full RST syntax, docstrings rarely contain full-featured directive. Maintainers are confronted to the following dilemma:

- keep the docstrings simple. This means mostly text-based docstrings with few directive for efficient readability. The end-user may be exposed to raw docstring, there is no on-the-fly directive interpretation. This is the case for tools such as IPython and Jupyter.

- write an extensive docstring. This includes references, and directive that potentially creates graphics, tables and more, allowing an enriched end-user experience. However this may be computationally intensive, and executing code to view docs could be a security risk.

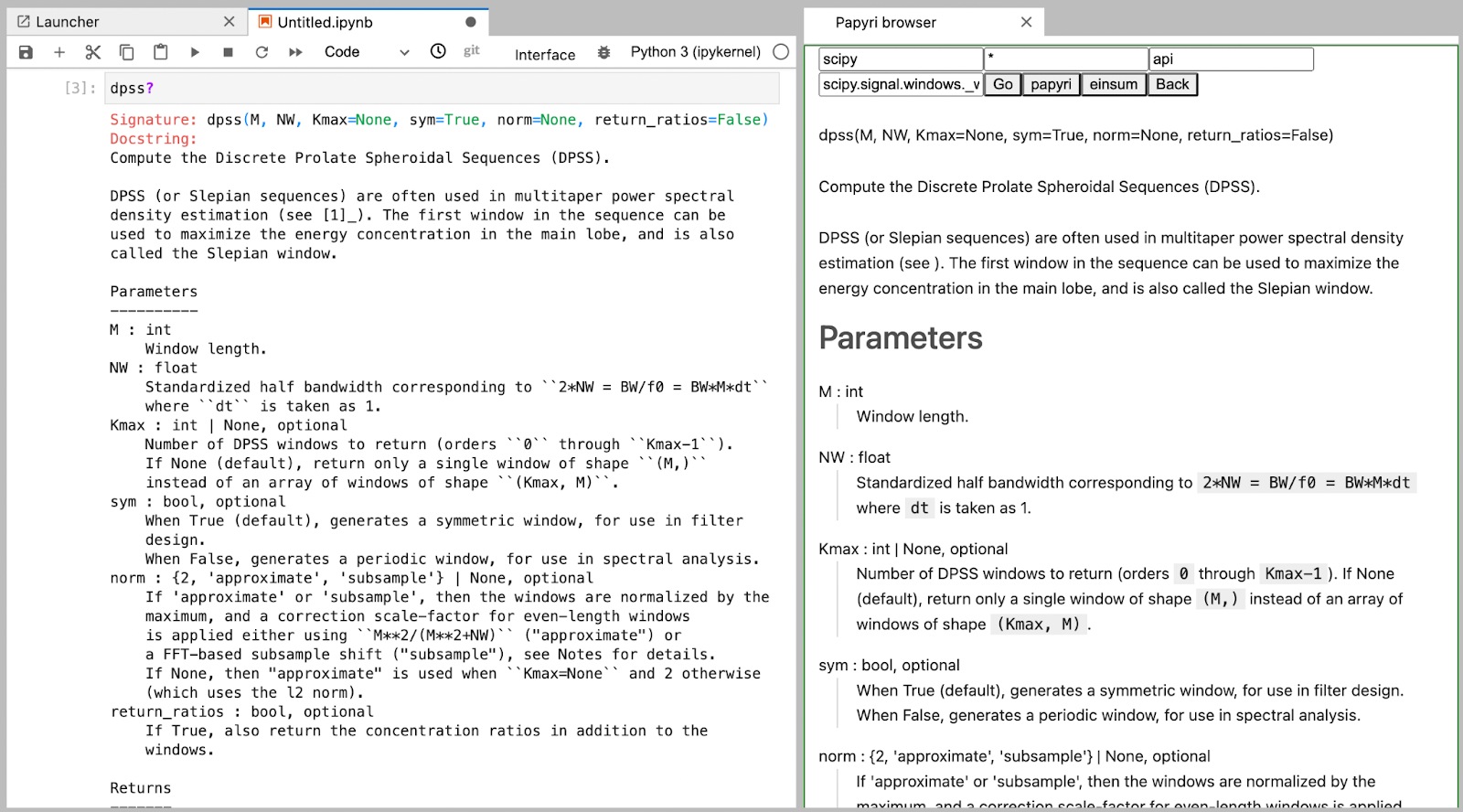

Other factors impact this choice: (i) users, (ii) format, (iii) runtime. IDE users or non-Terminal users motivate to push for extensive docstrings. Tools like Docrepr can mitigate this problem by allowing partial rendering. However, users are often exposed to raw docstrings (see for example the SymPy discussion [2] on how equations should be displayed in docstrings, and left panel of Figure Figure 1). In terms of format, markdown is appealing, however inconsistencies in the rendering will be created between libraries. Finally, some libraries can dynamically modify their docstring at runtime. While this sometime avoids using directives, it ends up being more expensive (runtime costs, complex maintenance, and contribution costs).

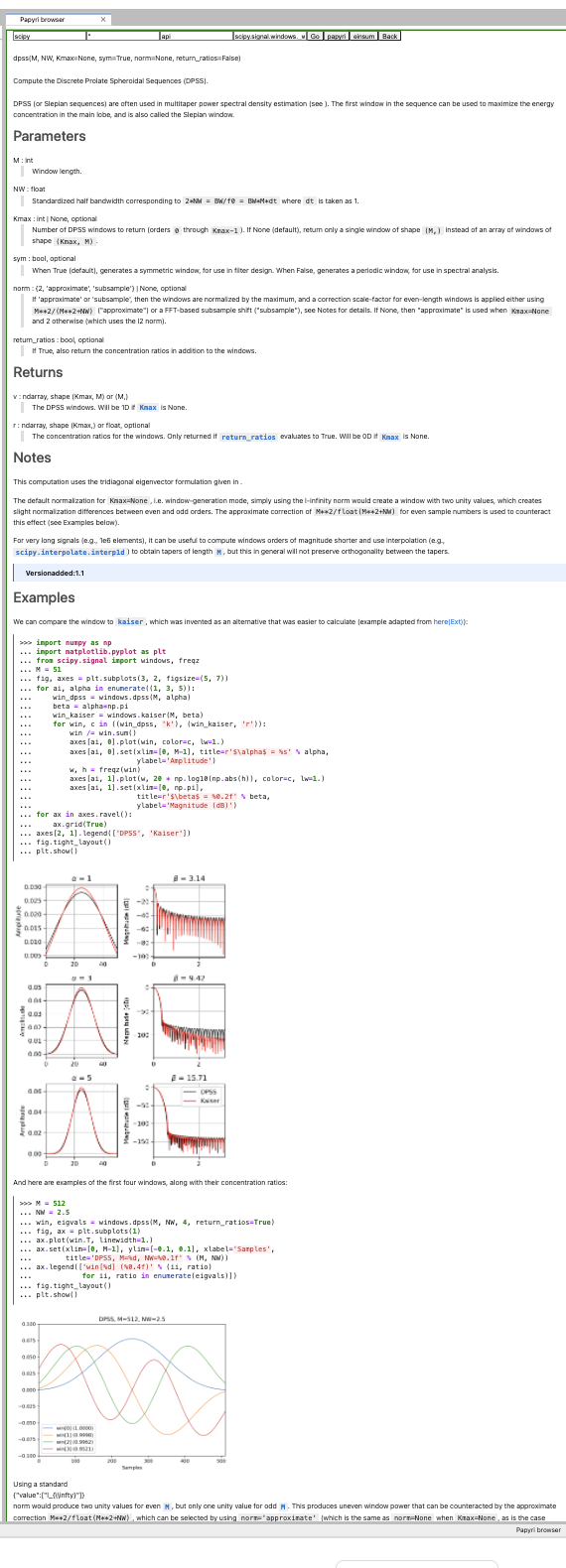

Figure 1:The following screenshot shows the help for scipy.signal.dpss, as

currently accessible (left), as shown by Papyri for Jupyterlab

extension (right). An extended version of the right pannel is displayed in

Figure 4.

Objectives of the project¶

We now layout the objectives of the Papyri documentation framework. Let us emphasize that the project is in no way intended to replace or cover many features included in well-established documentation tools such as Sphinx or Jupyter-book. Those projects are extremely flexible and meet the needs of their users for publishing a standalone documentation website of PDFs. The Papyri project addresses specific documentation challenges (mentioned above), we present below what is (and what is not) the scope of work.

Goal (a): design a non-generic (non fully customisable) website builder. When authors want or need complete control of the output and wide personalisation options, or branding, then Papyri is not likely the project to look at. That is to say single-project websites where appearance, layout, domain need to be controlled by the author is not part of the objectives.

Goal (b): create a uniform documentation structure and syntax. The Papyri project prescribes stricter requirements in terms of format, structure, and syntax compared to other tools such as Docutils and Sphinx. When possible, the documentation follows the Diátaxis Framework Diataxis, n.d.. This provides a uniform documentation setup and syntax, simplifying contributions to the project and easing error catching at compile time. Such strict environment is qualitatively supported by a number of documentation fixes done upstream during the development stage of the project [3]. Since Papyri is not fully customisable, users who are already using documentation tools such as Sphinx, mkdocs MkDocs, n.d. and others should expect their project to require minor modifications to work with Papyri.

Goal (c): provide accessibility and user proficiency. Accessibility is a top priority of the project. To that aim, items are associated to semantic meaning as much as possible, and documentation rendering is separated from documentation building phase. That way, accessibility features such as high contract themes (for better text-to-speech (TTS) raw data), early example highlights (for newcomers) and type annotation (for advanced users) can be quickly available. With the uniform documentation structure, this provides a coherent experience where users become more comfortable finding information in a single location (see Figure 1).

Goal (d): make documentation building simple, fast, and independent. One objective of the project is to make documentation installation and rendering relatively straightforward and fast. To that aim, the project includes relative independence of documentation building across libraries, allowing bidirectional cross links (i.e. both forward and backward links between pages) to be maintained more easily. In other words, a single library can be built without the need to access documentation from another. Also, the project should include straightforward lookup documentation for an object from the interactive read–eval–print loop (REPL). Finally, efforts are put to limit the installation speed (to avoid polynomial growth when installing packages on large distributed systems).

The Papyri solution¶

In this section we describe in more detail how Papyri has been implemented to address the objectives mentioned above.

Making documentation a multi-step process¶

When using current documentation tools, customisation made by maintainers usually falls into the following two categories:

- simpler input convenience,

- modification of final rendering.

This first category often requires arbitrary code execution and must import the

library currently being built. This is the case for example for the use of .. code-block:::, or custom :rc: directive. The second one offers a more user

friendly environment. For example,

sphinx-copybutton Sphinx Copybutton, n.d. adds a button to easily copy code snippets in a single

click, and pydata-sphinx-theme Pydata Sphinx Theme, n.d. or sphinx-rtd-dark-mode provide a different

appearance. As a consequence, developers must make choices on behalf of their

end-users: this may concern syntax highlights, type annotations display,

light/dark theme.

Being able to modify extensions and re-render the documentation without the rebuilding and executing stage is quite appealing. Thus, the building phase in Papyri (collecting documentation information) is separated from the rendering phase (Objective (c)): at this step, Papyri has no knowledge and no configuration options that permit to modify the appearance of the final documentation. Additionally, the optional rendering process has no knowledge of the building step, and can be run without accessing the libraries involved.

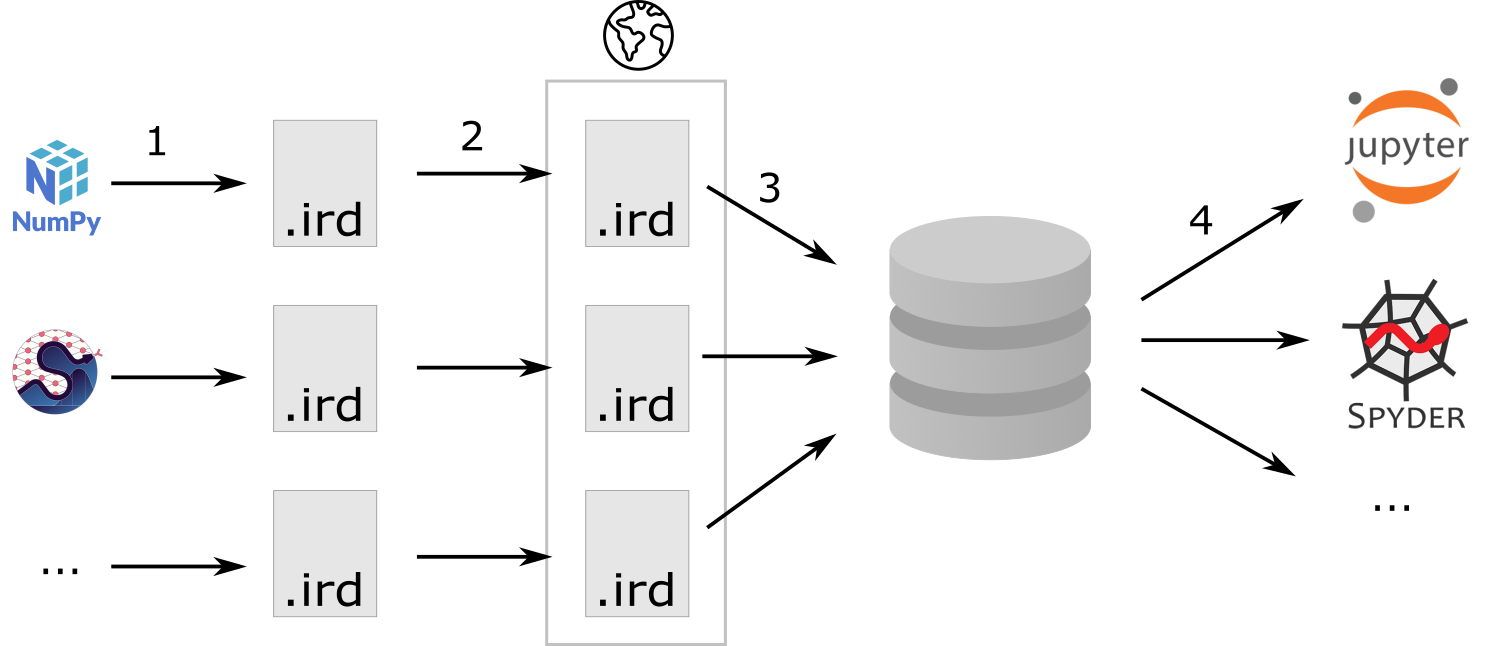

This kind of technique is commonly used in the field of compilers with the usage of Single Compilation Unit Single Compilation Unit, n.d. and Intermediate Representation Intermediate representation, n.d., but to our knowledge, it has not been implemented for documentation in the Python ecosystem. As mentioned before, this separation is key to achieving many features proposed in Objectives (c), (d) (see Figure Figure 2).

Figure 2:Sketch representing how to build documentation with Papyri. Step 1: Each project builds an IRD bundle that contains semantic information about the project documentation. Step 2: the IRD bundles are published online. Step 3: users install IRD bundles locally on their machine, pages get crosslinked, indexed, etc. Step 4: IDEs render documentation on-the-fly, taking into consideration users’ preferences.

Intermediate Representation for Documentation (IRD)¶

IRD format¶

Papyri relies on standard interchangeable “Intermediate Representation for Documentation” (IRD) format. This allows to reduce operation complexity of the documentation build. For example, given M documentation producers and N renderers, a full documentation build would be O(MN) (each renderer needs to understand each producer). If each producer only cares about producing IRD, and if each renderer only consumes it, then one can reduce to O(M+N). Additionally, one can take IRD from multiple producers at once, and render them all to a single target, breaking the silos between libraries.

At the moment, IRD files are currently separated into four main categories roughly following the Diátaxis framework Diataxis, n.d. and some technical needs:

- API files describe the documentation for a single object, expressed as a JSON object. When possible, the information is encoded semantically (Objective (c)). Files are organized based on the fully-qualified name of the Python object they reference, and contain either absolute reference to another object (library, version and identifier), or delayed references to objects that may exist in another library. Some extra per-object meta information like file/line number of definitions can be stored as well.

- Narrative files are similar to API files, except that they do not represent a given object, but possess a previous/next page. They are organised in an ordered tree related to the table of content.

- Example files are a non-ordered collection of files.

- Assets files are untouched binary resource archive files that can be referenced by any of the above three ones. They are the only ones that contain backward references, and no forward references.

In addition to the four categories above, metadata about the current package is stored: this includes library name, current version, PyPi name, GitHub repository slug [4], maintainers’ names, logo, issue tracker and others. In particular, metadata allows us to auto-generate links to issue trackers, and to source files when rendering. In order to properly resolve some references and normalize links convention, we also store a mapping from fully qualified names to canonical ones.

Let us make some remarks about the current stage of IRD format. The exact structure of package metadata has not been defined yet. At the moment it is reduced to the minimum functionality. While formats such as codemeta CodeMeta, n.d. could be adopted, in order to avoid information duplication we rely on metadata either present in the published packages already or extracted from Github repository sources. Also, IRD files must be standardized in order to achieve a uniform syntax structure (Objective (b)). In this paper, we do not discuss IRD files distribution. Last, the final specification of IRD files is still in progress and regularly undergoes major changes (even now). Thus, we invite contributors to consult the current state of implementation on the GitHub repository Papyri, n.d.. Once the IRD format is more stable, this will be published as a JSON schema, with full specification and more in-depth description.

IRD bundles¶

Once a library has collected IRD representation for all documentation items (functions, class, narrative sections, tutorials, examples), Papyri consolidates them into what we will refer to as IRD bundles. A Bundle gathers all IRD files and metadata for a single version of a library[5]. Bundles are a convenient unit to speak about publication, installation, or update of a given library documentation files.

Unlike package installation, IRD bundles do not have the notion of dependencies. Thus, a fully fledged package manager is not necessary, and one can simply download corresponding files and unpack them at the installation phase.

Additionally, IRD bundles for multiple versions of the same library (or conflicting libraries) are not inherently problematic as they can be shared across multiple environments.

From a security standpoint, installing IRD bundles does not require the execution of arbitrary code. This is a critical element for adoption in deployments. There exists as well an opportunity to provide localized variants at the IRD installation time (IRD bundle translations haven’t been explored exhaustively at the moment).

IRD and high level usage¶

Papyri-based documentation involves three broad categories of stakeholders (library maintainers, end-users, IDE developers), and processes. This leads to certain requirements for IRD files and bundles.

On the maintainers’ side, the goal is to ensure that Papyri can build IRD files, and publish IRD bundles. Creation of IRD files and bundles is the most computationally intensive step. It may require complex dependencies, or specific plugins. Thus, this can be a multi-step process, or one can use external tooling (not related to Papyri nor using Python) to create them. Visual appearance and rendering of documentation is not taken into account in this process. Overall, building IRD files and bundles takes about the same amount of time as running a full Sphinx build. The limiting factor is often associated to executing library examples and code snippets. For example, building SciPy & NumPy documentation IRD files on a 2021 Macbook Pro M1 (base model), including executing examples in most docstrings and type inferring most examples (with most variables semantically inferred) can take several minutes.

End-users are responsible for installing desired IRD bundles. In most cases, it will consist of IRD bundles from already installed libraries. While Papyri is not currently integrated with package managers or IDEs, one could imagine this process being automatic, or on demand. This step should be fairly efficient as it mostly requires downloading and unpacking IRD files.

Finally, IDEs developers want to make sure IRD files can be properly rendered and browsed by their users when requested. This may potentially take into account users’ preferences, and may provide added values such as indexing, searching, bookmarks and others, as seen in rustsdocs, devdocs.io.

Current implementation¶

We present here some of the technological choices made in the current Papyri implementation. At the moment, it is only targeting a subset of projects and users that could make use of IRD files and bundles. As a consequence, it is constrained in order to minimize the current scope and efforts development. Understanding the implementation is not necessary to use Papyri neither as a project maintainer nor as a user, but it can help understanding some of the current limitations.

Additionally, nothing prevents alternatives and complementary implementations with different choices: as long as other implementations can produce (or consume) IRD bundles, they should be perfectly compatible and work together.

The following sections are thus mostly informative to understand the state of the current code base. In particular we restricted ourselves to:

- Producing IRD bundles for the core scientific Python projects (Numpy, SciPy, Matplotlib...)

- Rendering IRD documentation for a single user on their local machine.

Finally, some of the technological choices have no other justification than the main developer having interests in them, or making iterations on IRD format and main code base faster.

IRD files generation¶

The current implementation of Papyri only targets some compatibility with Sphinx (a website and PDF documentation builder), reStructuredText (RST) as narrative documentation syntax and Numpydoc (both a project and standard for docstring formatting).

These are widely used by a majority of the core scientific Python ecosystem, and thus having Papyri and IRD bundles compatible with existing projects is critical. We estimate that about 85%-90% of current documentation pages being built with Sphinx, RST and Numpydoc can be built with Papyri. Future work includes extensions to be compatible with MyST (a project to bring markdown syntax to Sphinx), but this is not a priority.

To understand RST Syntax in narrative documentation, RST documents need to be parsed. To do so, Papyri uses tree-sitter Tree-sitter, n.d. and tree-sitter-rst Tree-sitter RST, n.d. projects, allowing us to extract an “Abstract Syntax Tree” (AST) from the text files. When using tree-sitter, AST nodes contain bytes-offsets into the original text buffer. Then one can easily “unparse” an AST node when necessary. This is relatively convenient for handling custom directives and edge cases (for instance, when projects rely on a loose definition of the RST syntax). Let us provide an example: RST directives are usually of the form:

.. directive:: arguments

bodyWhile technically there is no space before the ::, Docutils and Sphinx will not create errors when building the documentation. Due to our choice of a rigid (but unified) structure, we use tree-sitter that indicates an error node if there is an extra space. This allows us to check for error nodes, unparse, add heuristics to restore a proper syntax, then parse again to obtain the new node.

Alternatively, a number of directives like warnings, notes

admonitions still contain valid RST. Instead of storing the directive with

the raw text, we parse the full document (potentially finding invalid syntax),

and unparse to the raw text only if the directive requires it.

Serialisation of data structure into IRD files is currently using a custom serialiser. Future work includes maybe swapping to msgspec Msgspec, n.d.. The AST objects are completely typed, however they contain a number of unions and sequences of unions. It turns out, many frameworks like pydantic Pydantic, n.d. do not support sequences of unions where each item in the union may be of a different type. To our knowledge, there are just few other documentation related projects that treat AST as an intermediate object with a stable format that can be manipulated by external tools. In particular, the most popular one is Pandoc Pandoc, n.d., a project meant to convert from many document types to plenty of other ones.

The current Papyri strategy is to type-infer all code examples with Jedi Jedi, n.d., and pre-syntax highlight using pygments when possible.

IRD File Installation¶

Download and installation of IRD files is done concurrently using httpx HTTPX, n.d., with Trio Trio, n.d. as an async framework, allowing us to download files concurrently.

The current implementation of Papyri targets Python documentation and is written in Python. We can then query the existing version of Python libraries installed, and infer the appropriate version of the requested documentation. At the moment, the implementation is set to tentatively guess relevant libraries versions when the exact version number is missing from the install command.

For convenience and performance, IRD bundles are being post-processed and stored in a different format. For local rendering, we mostly need to perform the following operations:

- Query graph information about cross-links across documents.

- Render a single page.

- Access raw data (e.g. images).

We also assume that IRD files may be infrequently updated, that disk space is limited, and that installing or running services (like a database server) are not necessary available. This provides an adapted framework to test Papyri on an end-user machine.

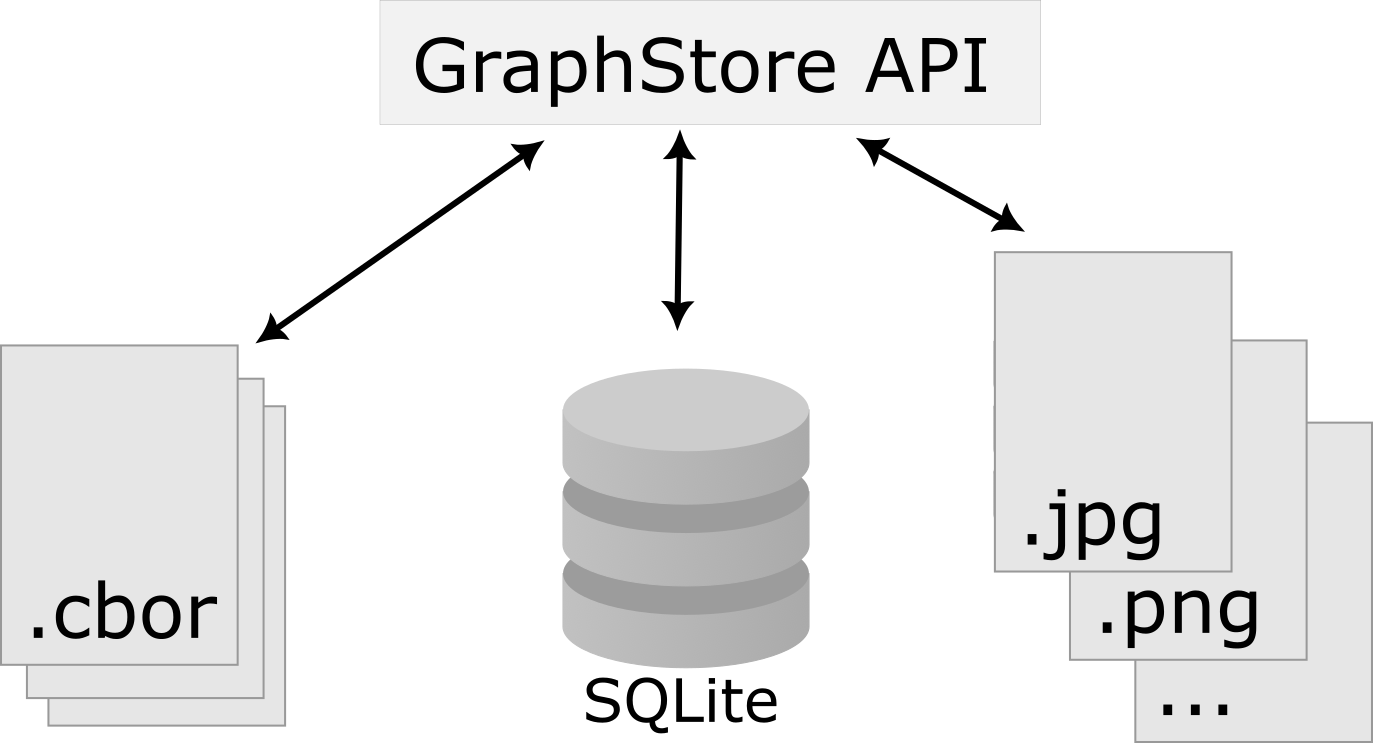

With those requirements we decided to use a combination of SQLite (an in-process database engine), Concise Binary Object Representation (CBOR) and raw storage to better reflect the access pattern (see Figure 3).

SQLite allows us to easily query for object existence, and graph information (relationship between objects) at runtime. It is optimized for infrequent reading access. Currently many queries are done at runtime, when rendering documentation. The goal is to move most of SQLite information resolving step at the installation time (such as looking for inter-libraries links) once the codebase and IRD format have stabilized. SQLite is less strongly typed than other relational or graph database and needs custom logic, but is ubiquitous on all systems and does not need a separate server process, making it an easy choice of database.

CBOR is a more space efficient alternative to JSON. In particular, keys in IRD are often highly redundant, and can be highly optimized when using CBOR. Storing IRD in CBOR thus reduces disk usage and can also allow faster deserialization without requiring potentially CPU intensive compression/decompression. This is a good compromise for potentially low performance users’ machines.

Raw storage is used for binary blobs which need to be accessed without further processing. This typically refers to images, and raw storage can be accessed with standard tools like image viewers.

Finally, access to all of these resources is provided via an internal

GraphStore API which is agnostic of the backend, but ensures consistency of

operations like adding/removing/replacing documents. Figure 3 summarizes this process.

Figure 3:Sketch representing how Papyri stores information in 3 different format depending on

access patterns: a SQLite database for relationship information, on-disk CBOR

files for more compact storate of IRD, and RAW files (e.g. Images). A GraphStore

API abstracts all access and takes care of maintinaing consistency.

Of course the above choices depend on the context where documentation is rendered and viewed. For example, an online archive intended to browse documentation for multiple projects and versions may decide to use an actual graph database for object relationship, and store other files on a Content Delivery Network or blob storage for random access.

Documentation Rendering¶

The current Papyri implementation includes a certain number of rendering engines (presented below). Each of them mostly consists of fetching a single page with its metadata, and walking through the IRD AST tree, and rendering each node with users’ preferences.

- An ASCII terminal renders using Jinja2 Jinja2, n.d.. This can be useful for piping

documentation to other tools like

grep,less,cat. Then one can work in a highly restricted environment, making sure that reading the documentation is coherent. This can serve as a proxy for screen reading. - A Textual User Interface browser renders using

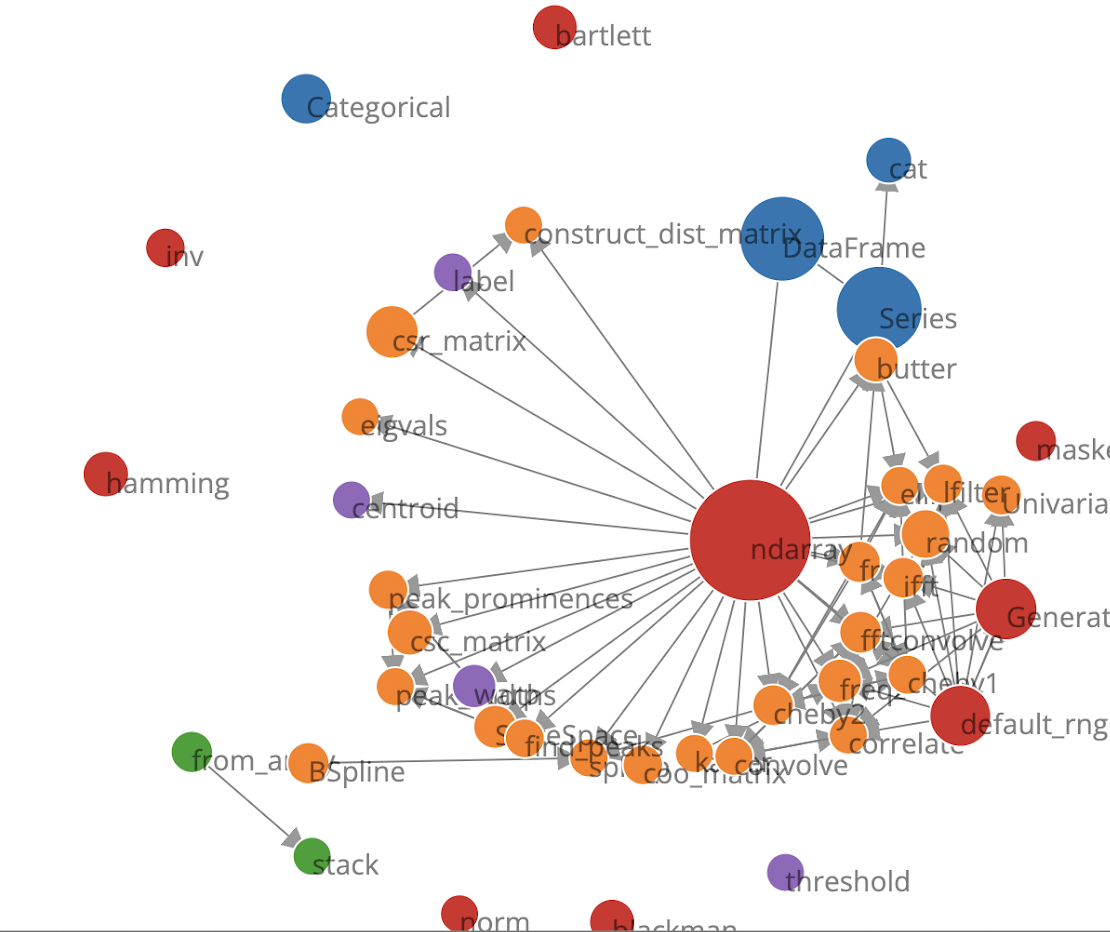

urwid. Navigation within the terminal is possible, one can reflow long lines on resized windows, and even open image files in external editors. Nonetheless, several bugs have been encountered in urwid. The project aims at replacing the CLI IPython question mark operator (obj?) interface (which currently only shows raw docstrings) in urwid with a new one written with Rich/Textual. For this interface, having images stored raw on disk is useful as it allows us to directly call into a system image viewer to display them. - A JIT rendering engine uses Jinja2, Quart Quart, n.d., Trio. Quart is an async version of flask Flask, n.d.. This option contains the most features, and therefore is the main one used for development. This environment lets us iterate over the rendering engine rapidly. When exploring the User Interface design and navigation, we found that a list of back references has limited uses. Indeed, it is can be challenging to judge the relevance of back references, as well as their relationship to each other. By playing with a network graph visualisation (see Figure 5), we can identify clusters of similar information within back references. Of course, this identification has limits especially when pages have a large number of back references (where the graph becomes too busy). This illustrate as well a strength of the Papyri architecture: creating this network visualization did not require any regeneration of the documentation, one simply updates the template and re-renders the current page as needed.

- A static AOT rendering of all the existing pages that can be

rendered ahead of time uses the same class as the JIT rendering. Basically, this loops through all entries in the SQLite database and renders

each item independently. This renderer is mostly used for exhaustive testing and performance measures for Papyri. This can render most of the API documentation of IPython, Astropy The Astropy Collaboration et al., 2018, Dask and distributed Dask Development Team, 2016, Matplotlib Hunter, 2007 Caswell et al., 2022, Networkx Hagberg et al., 2008, NumPy Harris et al., 2020,

Pandas, Papyri, SciPy,Scikit-imageand others. It can represent ~28000 pages in ~60 seconds (that is ~450 pages/s on a recent Macbook pro M1).

For all of the above renderers, profiling shows that documentation rendering is mostly limited by object de-serialisation from disk and Jinja2 templating engine. In the early project development phase, we attempted to write a static HTML renderer in a compiled language (like Rust, using compiled and typed checked templates). This provided a speedup of roughly a factor 10. However, its implementation is now out of sync with the main Papyri code base.

Finally, a JupyterLab extension is currently in progress. The documentation then presents itself as

a side-panel and is capable of basic browsing and rendering (see Figure 1 and Figure 4). The model uses typescript,

react and native JupyterLab component. Future goals include improving/replacing the

JupyterLab’s question mark operator (obj?) and the JupyterLab Inspector (when possible). A screenshot of the current development version of the JupyterLab

extension can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4:Example of extended view of the Papyri documentation for Jupyterlab extension (here for SciPy). Code examples can now include plots. Most token in each examples are linked to the corresponding page. Early navigation bar is visible at the top.

Figure 5:Local graph (made with D3.js (n.d.)) representing the connections among the most important nodes around current page across many libraries, when viewing numpy.ndarray.

Nodes are sized with respect to the number of incomming links, and colored with respect to their library. This graph is generated at rendering time, and is updated depending on the libraries currently installed. This graph helps identify related functions and documentation. It can become challenging to read for highly connected items as seen here for numpy.ndarray.

Challenges¶

We mentioned above some limitations we encountered (in rendering usage for instance) and what will be done in the future to address them. We provide below some limitations related to syntax choices, and broader opportunities that arise from the Papyri project.

Limitations¶

The decoupling of the building and rendering phases is key in Papyri. However, it requires us to come up with a method that uniquely identifies each object. In particular, this is essential in order to link any object documentation without accessing the IRD bundles build from all the libraries. To that aim, we use the fully qualified names of an object. Namely, each object is identified by the concatenation of the module in which it is defined, with its local name. Nonetheless, several particular cases need specific treatment.

To mirror the Python syntax, is it easy to use

.to concatenate both parts. Unfortunately, that leads to some ambiguity when modules re-export functions have the same name. For example, if one types# module mylib/__init__.py from .mything import mythingthen

mylib.mythingis ambiguous both with respect to themythingsubmodule, and the reexported object. In future versions, the chosen convention will use:as a module/name separator.Decorated functions or other dynamic approaches to expose functions to users end up having

<local>>in their fully qualified names, which is invalid.Many built-in functions (

np.sin,np.cos, etc.) do not have a fully qualified name that can be extracted by object introspection. We believe it should be possible to identify those via other means like docstring hash (to be explored).Fully qualified names are often not canonical names (i.e. the name typically used for import). While we made efforts to create a mapping from one to another, finding the canonical name automatically is not always straightforward.

There are also challenges with case sensitivity. For example for MacOS file systems, a couple of objects may unfortunately refer to the same IRD file on disk. To address this, a case-sensitive hash is appended at the end of the filename.

Many libraries have a syntax that

looksright once rendered to HTML while not following proper syntax, or a syntax that relies on specificities of Docutils and Sphinx rendering/parsing.Many custom directive plugins cannot be reused from Sphinx. These will need to be reimplemented.

Future possibilities¶

Beyond what has been presented in this paper, there are several opportunities to improve and extend what Papyri can allow for the scientific Python ecosystem.

The first area is the ability to build IRD bundles on Continuous Integration platforms. Services like GitHub action, Azure pipeline and many others are already setup to test packages. We hope to leverage this infrastructure to build IRD files and make them available to users.

A second area is hosting of intermediate IRD files. While the current prototype is hosted by http index using GitHub pages, it is likely not a sustainable hosting platform as disk space is limited. To our knowledge, IRD files are smaller in size than HTML documentation, we hope that other platforms like Read the Docs can be leveraged. This could provide a single domain that renders the documentation for multiple libraries, thus avoiding the display of many library subdomains. This contributes to giving a more unified experience for users.

It should be possible for projects to avoid using many dynamic docstrings

interpolation that are used to document *args and **kwargs. This would

make sources easier to read, and potentially have some speedup at the library import time.

Once a (given and appropriately used by its users) library uses an IDE that supports Papyri for documentation, docstring syntax could be exchanged for markdown.

As IRD files are structured, it should be feasible to provide cross-version information in the documentation. For example, if one installs multiple versions of IRD bundles for a library, then assuming the user does not use the latest version, the renderer could inspect IRD files from previous/future versions to indicate the range of versions for which the documentation has not changed. Upon additional efforts, it should be possible to infer when a parameter was removed, or will be removed, or to simply display the difference between two versions.

Conclusion¶

To address some of the current limitations in documentation accessibility, building and maintaining, we have provided a new documentation framework called Papyri. We presented its features and underlying implementation choices (such as crosslink maintenance, decoupling building and rendering phases, enriching the rendering features, using the IRD format to create a unified syntax structure, etc.). While the project is still at its early stage, clear impacts can already be seen on the availability of high-quality documentation for end-users, and on the workload reduction for maintainers. Building IRD format opened a wide range of technical possibilities, and contributes to improving users’ experience (and therefore the success of the scientific Python ecosystem). This may become necessary for users to navigate in an exponentially growing ecosystem.

Funding¶

M. B. received a 2-year grant from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) Essential Open Source Software for Science (EOS) – EOSS4-0000000017 via the NumFOCUS 501(3)c non profit to develop the Papyri project.

The authors want to thank S. Gallegos (author of tree-sitter-rst), J. L. Cano Rodríguez and E. Holscher (Read The Docs), C. Holdgraf (2i2c), B. Granger and F. Pérez (Jupyter Project), T. Allard and I. Presedo-Floyd (QuanSight) for their useful feedback and help on this project.

Copyright © 2022 Bussonnier & Carvalho. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

“slug” is the common term that refers to the various combinations of organization name/user name/repository name, that uniquely identifies a repository on a platform like GitHub.

One could have IRD bundles not attached to a particular library. For example, this can be done if an author wishes to provide only a set of examples or tutorials. We will not discuss this case further here.

- AOT

- ahead-of-time

- CBOR

- Concise Binary Object Representation

- CLI

- command line interface

- IDE

- integrated development environment

- IR

- intermediate representation

- IRD

- Intermediate Representation for Documentation

- JIT

- just-in-time

- LTO

- link-time optimization

- REPL

- read-eval-print loop

- RST

- reStructuredText

- Conda-Forge Community. (2015). The conda-forge Project: Community-based Software Distribution Built on the conda Package Format and Ecosystem. Zenodo. 10.5281/ZENODO.4774216

- Ahead-of-time compilation. (n.d.). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahead-of-time_compilation

- Just-in-time compilation. (n.d.). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Just-in-time_compilation

- Intermediate representation. (n.d.). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intermediate_representation

- Interprocedural optimization. (n.d.). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interprocedural_optimization

- Docutils. (n.d.). https://docutils.sourceforge.io/

- Sphinx. (n.d.). https://www.sphinx-doc.org/en/master/

- Read the Docs. (n.d.). https://readthedocs.org/

- Sphinx RTD Theme. (n.d.). https://sphinx-rtd-theme.readthedocs.io/en/stable/

- Jupyter Book. (n.d.). https://jupyterbook.org/

- MyST. (n.d.). https://myst-parser.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

- Docrepr. (n.d.). https://github.com/spyder-ide/docrepr

- Spyder. (n.d.). https://www.spyder-ide.org/

- Harris, C. R., Millman, K. J., van der Walt, S. J., Gommers, R., Virtanen, P., Cournapeau, D., Wieser, E., Taylor, J., Berg, S., Smith, N. J., Kern, R., Picus, M., Hoyer, S., van Kerkwijk, M. H., Brett, M., Haldane, A., del Río, J. F., Wiebe, M., Peterson, P., … Oliphant, T. E. (2020). Array programming with NumPy. Nature, 585(7825), 357–362. 10.1038/s41586-020-2649-2

- Virtanen, P., Gommers, R., Oliphant, T. E., Haberland, M., Reddy, T., Cournapeau, D., Burovski, E., Peterson, P., Weckesser, W., Bright, J., van der Walt, S. J., Brett, M., Wilson, J., Millman, K. J., Mayorov, N., Nelson, A. R. J., Jones, E., Kern, R., Larson, E., … Vázquez-Baeza, Y. (2020). SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nature Methods, 17(3), 261–272. 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2