Phylogeography: Analysis of genetic and climatic data of SARS-CoV-2

Abstract¶

Due to the fact that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic reaches its peak, researchers around the globe are combining efforts to investigate the genetics of different variants to better deal with its distribution. This paper discusses phylogeographic approaches to examine how patterns of divergence within SARS-CoV-2 coincide with geographic features, such as climatic features.

First, we propose a python-based bioinformatic pipeline called aPhylogeo for phylogeographic analysis written in Python 3 that help researchers better understand the distribution of the virus in specific regions via a configuration file, and then run all the analysis operations in a single run. In particular, the aPhylogeo tool determines which parts of the genetic sequence undergo a high mutation rate depending on geographic conditions, using a sliding window that moves along the genetic sequence alignment in user-defined steps and a window size. As a Python-based cross-platform program, aPhylogeo works on Windows®, MacOS X® and GNU/Linux. The implementation of this pipeline is publicly available on GitHub (https://

Introduction¶

The global pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is at its peak and more and more variants of SARS-CoV-2 were described over time. Among these, some are considered variants of concern (VOC) by the World Health Organization (WHO) due to their impact on global public health, such as Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), Delta (B.1.617.2), and Omicron (B.1.1.529) Cascella et al., 2022. Although significant progress was made in vaccine development and mass vaccination is being implemented in many countries, the continued emergence of new variants of SARS-CoV-2 threatens to reverse the progress made to date. Researchers around the world collaborate to better understand the genetics of the different variants, along with the factors that influence the epidemiology of this infectious disease. Genetic studies of the different variants contributed to the development of vaccines to better combat the spread of the virus. Studying the factors (e.g., environment, host, agent of transmission) that influence epidemiology helps us to limit the continued spread of infection and prepare for the future re-emergence of diseases caused by subtypes of coronavirus Lin et al., 2006. However, few studies report associations between environmental factors and the genetics of different variants. Different variants of SARS-CoV-2 are expected to spread differently depending on geographical conditions, such as the meteorological parameters. The main objective of this study is to find clear correlations between genetics and geographic distribution of different variants of SARS-CoV-2.

Several studies showed that COVID-19 cases and related climatic factors correlate significantly with each other Oliveiros et al., 2020Sobral et al., 2020Sabarathinam et al., 2022. Oliveiros et al. (2020) reported a decrease in the rate of SARS-CoV-2 progression with the onset of spring and summer in the northern hemisphere. Sobral et al. (2020) suggested a negative correlation between mean temperature by country and the number of SARS-CoV-2 infections, along with a positive correlation between rainfall and SARS-CoV-2 transmission. This contrasts with the results of the study by Sabarathinam et al. (2022), which showed that an increase in temperature led to an increase in the spread of SARS-CoV-2. The results of Chen et al. (2021) imply that a country located 1000 km closer to the equator can expect 33% fewer cases of SARS-CoV-2 per million population. Some virus variants may be more stable in environments with specific climatic factors. Sabarathinam et al. (2022) compared mutation patterns of SARS-CoV-2 with time series of changes in precipitation, humidity, and temperature. They suggested that temperatures between 43°F and 54°F, humidity of 67-75%, and precipitation of 2-4 mm may be the optimal environment for the transition of the mutant form from D614 to G614.

In this study, we examine the geospatial lineage of SARS-CoV-2 by combining genetic data and metadata from associated sampling locations. Thus, an association between genetics and the geographic distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants can be found. We focus on developing a new algorithm to find relationships between a reference tree (i.e., a tree of geographic species distributions, a temperature tree, a habitat precipitation tree, or others) with their genetic compositions. This new algorithm can help find which genes or which subparts of a gene are sensitive or favorable to a given environment.

Problem statement and proposal¶

Phylogeography is the study of the principles and processes that govern the distribution of genealogical lineages, particularly at the intraspecific level. The geographic distribution of species is often correlated with the patterns associated with the species’ genes Avise & others, 2000Knowles & Maddison, 2002. In a phylogeographic study, three major processes should be considered (see Nagylaki (1992) for more details), which are:

- Genetic drift is the result of allele sampling errors. These errors are due to generational transmission of alleles and geographical barriers. Genetic drift is a function of the size of the population. Indeed, the larger the population, the lower the genetic drift. This is explained by the ability to maintain genetic diversity in the original population. By convention, we say that an allele is fixed if it reaches the frequency of 100%, and that it is lost if it reaches the frequency of 0%.

- Gene flow or migration is an important process for conducting a phylogeographic study. It is the transfer of alleles from one population to another, increasing intrapopulation diversity and decreasing interpopulation diversity.

- There are many selections in all species. Here we indicate the two most important of them, if they are essential for a phylogeographic study. (a) Sexual selection is a phenomenon resulting from an attractive characteristic between two species. Therefore, this selection is a function of the size of the population. (b) Natural selection is a function of fertility, mortality, and adaptation of a species to a habitat.

Populations living in different environments with varying climatic conditions are subject to pressures that can lead to evolutionary divergence and reproductive isolation Orr & Smith, 1998Schluter, 2001. Phylogeny and geography are then correlated. This study, therefore, aims to present an algorithm to show the possible correlation between certain genes or gene fragments and the geographical distribution of species.

Most studies in phylogeography consider only genetic data without directly considering climatic data. They indirectly take this information as a basis for locating the habitat of the species. We have developed the first version of a phylogeography that integrates climate data. The sliding window strategy provides more robust results, as it particularly highlights the areas sensitive to climate adaptation.

Methods and Python scripts¶

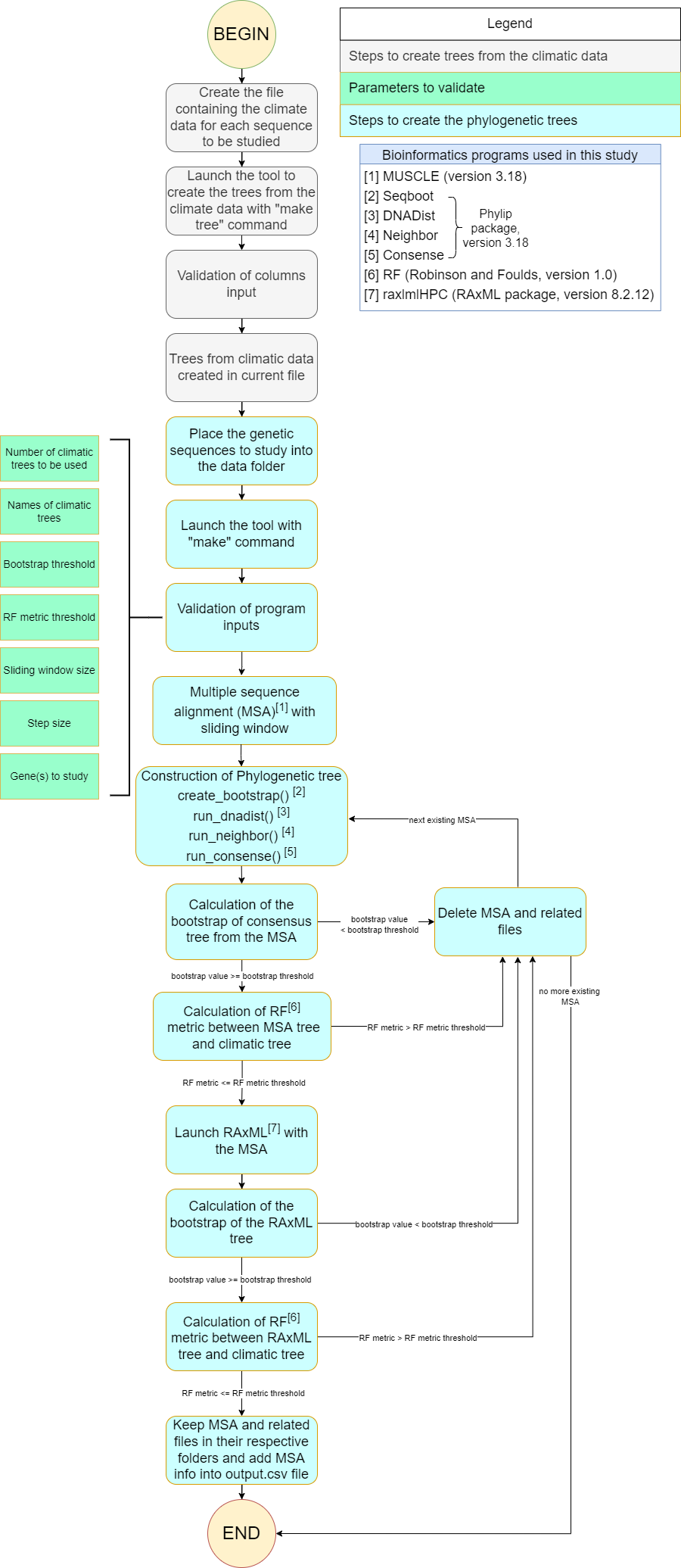

In order to achieve our goal, we designed a workflow and then developed a script in Python version 3.9 called aPhylogeo for phylogeographic analysis (see Li et al. (2022) for more details). It interacts with multiple bioinformatic programs, taking climatic data and nucleotide data as input, and performs multiple phylogenetic analyses on nucleotide sequencing data using a sliding window approach. The process is divided into three main steps (see Figure 1).

The first step involves collecting data to search for quality viral sequences that are essential for the conditions of our results. All sequences were retrieved from the NCBI Virus website (National Center for Biotechnology Information, https://

In the second step, trees are created with climatic data and genetic data, respectively. For climatic data, we calculated the dissimilarity between each pair of variants (i.e., from different climatic conditions), resulting in a symmetric square matrix. From this matrix, the neighbor joining algorithm was used to construct the climate tree. The same approach was implemented for genetic data. Using nucleotide sequences from the 38 SARS-CoV-2 lineages, phylogenetic reconstruction is repeated to construct genetic trees, considering only the data within a window that moves along the alignment in user-defined steps and window size (their length is denoted by the number of base pairs (bp)).

In the third step, the phylogenetic trees constructed in each sliding window are compared to the climatic trees using the Robinson and Foulds (RF) topological distance Robinson & Foulds, 1981. The distance was normalized by , where is the number of leaves (i.e., taxa). The proposed approach considers bootstrapping. The implementation of sliding window technology provides a more accurate identification of regions with high gene mutation rates.

As a result, we highlighted a correlation between parts of genes with a high rate of mutations depending on the geographic distribution of viruses, which emphasizes the emergence of new variants (i.e., Alpha, Beta, Delta, Gamma, and Omicron).

The creation of phylogenetic trees, as mentioned above, is an important part of the solution and includes the main steps of the developed pipeline. This function is intended for genetic data. The main parameters of this part are as follows:

def create_phylo_tree(gene,

window_size,

step_size,

bootstrap_threshold,

rf_threshold,

data_names):

number_seq = align_sequence(gene)

sliding_window(window_size, step_size)

...

for file in files:

try:

...

create_bootstrap()

run_dnadist()

run_neighbor()

run_consense()

filter_results(gene,

bootstrap_threshold,

rf_threshold,

data_names,

number_seq,

file))

...

except Exception as error:

raiseThis function takes gene data, window size, step size, bootstrap threshold, threshold for the Robinson and Foulds distance, and data names as input parameters. Then the function sequentially connects the main steps of the pipeline: align_sequence(gene), sliding_window(window_size, step_size), create_bootstrap(), run_dnadist(), run_neighbor(), run_consense(), and filter_results with parameters. As a result, we obtain a phylogenetic tree (or several trees), which is written to a file.

We have created a function (create_tree) to create the climate trees. The function is described as follow:

def create_tree(file_name, names):

for i in range(1, len(names)):

create_matrix(file_name,

names[0],

names[i],

"infile")

os.system("./exec/neighbor " +

"< input/input.txt")

subprocess.call(["mv",

"outtree",

"intree"])

subprocess.call(["rm",

"infile",

"outfile"])

os.system("./exec/consense "+

"< input/input.txt")

newick_file = names[i].replace(" ", "_") +

"_newick"

subprocess.call(["rm",

"outfile"])

subprocess.call(["mv",

"outtree",

newick_file])The sliding window strategy can detect genetic fragments depending on environmental parameters, but this work requires time-consuming data preprocessing and the use of several bioinformatics programs. For example, we need to verify that each sequence identifier in the sequencing data always matches the corresponding metadata. If samples are added or removed, we need to check whether the sequencing dataset matches the metadata and make changes accordingly. In the next stage, we need to align the sequences (multiple sequence alignment, MSA) and integrate all step by step into specific software such as MUSCLE Edgar, 2004, Phylip package (i.e. Seqboot, DNADist, Neighbor, and Consense) Felsenstein, 2005, RF Robinson & Foulds, 1981, and raxmlHPC Stamatakis, 2014. The use of each software requires expertise in bioinformatics. In addition, the intermediate analysis steps inevitably generate many files, the management of which not only consumes the time of the biologist, but is also subject to errors, which reduces the reproducibility of the study. At present, there are only a few systems designed to automate the analysis of phylogeography. In this context, the development of a computer program for a better understanding of the nature and evolution of coronavirus is essential for the advancement of clinical research.

The following sliding window function illustrates moving the sliding window through an alignment with window size and step size as parameters. The first 11 characters are allocated to species names, plus a space.

def sliding_window(window_size=0, step=0):

try:

f = open("infile", "r")

...

# slide the window along the sequence

start = 0

fin = start + window_size

while fin <= longueur:

index = 0

with open("out", "r") as f, ... as out:

...

for line in f:

if line != "\n":

espece = list_names[index]

nb_espace = 11 - len(espece)

out.write(espece)

for i in range(nb_espace):

out.write(" ")

out.write(line[debut:fin])

index = index + 1

out.close()

f.close()

start = start + step

fin = fin + step

except:

print("An error occurred.")

Figure 1:The workflow of the algorithm. The operations within this workflow include several blocks. The blocks are highlighted by three different colors. The first block (grey color) is responsible for creating the trees based on the climate data. The second block (green color) performs the function of input parameter validation. The third block (blue color) allows the creation of phylogenetic trees. This is the most important block and the basis of this study, through the results of which the user receives the output data with the necessary calculations.

Algorithmic complexity¶

The complexity of the algorithm described in the previous section depends on the complexity of the various external programs used and the number of windows that the alignment can contain, plus one for the total alignment that the program will process.

Recall the different complexities of the different external programs used in the algorithm:

- SeqBoot program:

- DNADist program:

- Neighbor program:

- Consense program:

- RaxML program:

- RF program: ,

where is a number of species (or taxa), is a number of replicates, is a size of the multiple sequence alignment (MSA), and is a number of refinement steps performed by the RaxML algorithm. For all and for all , the number of windows can be evaluated as follow (1):

where is a window size, and is a step.

Dataset¶

The following two principles were applied to select the samples for analysis.

- Selection of SARS-CoV-2 Pango lineages that are dispersed in different phylogenetic clusters whenever possible.

The Pango lineage nomenclature system is hierarchical and fine-scaled and is designed to capture the leading edge of pandemic transmission. Each Pango lineage aims to define an epidemiologically relevant phylogenetic cluster, for instance, an introduction into a distinct geographic area with evidence of onward transmission Rambaut et al., 2020. From one side, Pango lineages signify groups or clusters of infections with shared ancestry. If the entire pandemic can be thought of as a vast branching tree of transmission, then the Pango lineages represent individual branches within that tree. From another side, Pango lineages are intended to highlight epidemiologically relevant events, such as the appearance of the virus in a new location, a rapid increase in the number of cases, or the evolution of viruses with new phenotypes O’Toole et al., 2021. Therefore, to have some sequence diversity in the selected samples, we avoided selecting lineages belonging to the same or similar phylogenetic clusters. For example, among C.36, C.36.1, C.36.2, C.36.3 and C.36.3.1, only C.36 was used as a sample for analysis.

- Selection of the lineages that are clearly dominant in a particular region compared to other regions.

Through significant advances in the generation and exchange of SARS-CoV-2 genomic data in real time, international spread of lineages is tracked and recorded on the website (cov

We list four examples of the distribution of a set of lineages:

- Both lineages A.2.3 and B.1.1.107 have 100% distribution in the United Kingdom. Both lineages D.2 and D.3 have 100% distribution in Australia. B.1.1.172, L.4 and P.1.13 have 100% distribution in the United States. Finally, AH.1, AK.2, C.7 have 100% distribution in Switzerland, Germany, and Denmark, respectively.

- The country with the widest distribution of L.2 is the Netherlands (77.0%), followed by Germany (19.0%). Due to a 58% difference in the distribution of L.2 between the two locations, we consider the Netherlands as the main distribution country of L.2 and, therefore, it was selected as a sample.

- Similarly, the most predominant country of distribution of C.37 is Peru (44%), followed by Chile (19.0%), with a difference of 25%. Among all samples of this study, C.37 was the lineage with the least difference in distribution percentage between the two countries. Considering the need to increase the diversity of the geographical distribution of the samples, C.37 was also selected.

- In contrast, the distribution of C.6 is 17.0% in France, 14.0% in Angola, 13.0% in Portugal, and 8.0% in Switzerland, and we concluded that C.6 does not show a tendency in terms of geographic distribution and, therefore, was not included as a sample for analysis.

In accordance with the above principles, we selected 38 lineages with regional characteristics for further study. Based on location information, complete nucleotide sequencing data for these 38 lineages was collected from the NCBI Virus website (https://

Table 1:SARS-CoV-2 lineages analyzed. The lineage assignments covered in the table were last updated on March 1, 2022. Among all Pango lineages of SARS-CoV-2, 38 lineages were analyzed. Corresponding sequencing data were found in the NCBI database based on the date of earliest detection and country of most common. The table also marks the percentage of the virus in the most common country compared to all countries where the virus is present.

| Lineage | Most Common Country | Earliest Date | Sequence Accession |

| A.2.3 | United Kingdom 100.0% | 2020-03-12 | OW470304.1 |

| AE.2 | Bahrain 100.0% | 2020-06-23 | MW341474 |

| AH.1 | Switzerland 100.0% | 2021-01-05 | OD999779 |

| AK.2 | Germany 100.0% | 2020-09-19 | OU077014 |

| B.1.1.107 | United Kingdom 100.0% | 2020-06-06 | OA976647 |

| B.1.1.172 | USA 100.0% | 2020-04-06 | MW035925 |

| BA.2.24 | Japan 99.0% | 2022-01-27 | BS004276 |

| C.1 | South Africa 93.0% | 2020-04-16 | OM739053.1 |

| C.7 | Denmark 100.0% | 2020-05-11 | OU282540 |

| C.17 | Egypt 69.0% | 2020-04-04 | MZ380247 |

| C.20 | Switzerland 85.0% | 2020-10-26 | OU007060 |

| C.23 | USA 90.0% | 2020-05-11 | ON134852 |

| C.31 | USA 87.0% | 2020-08-11 | OM052492 |

| C.36 | Egypt 34.0% | 2020-03-13 | MW828621 |

| C.37 | Peru 43.0% | 2021-02-02 | OL622102 |

| D.2 | Australia 100.0% | 2020-03-19 | MW320730 |

| D.3 | Australia 100.0% | 2020-06-14 | MW320869 |

| D.4 | United Kingdom 80.0% | 2020-08-13 | OA967683 |

| D.5 | Sweden 65.0% | 2020-10-12 | OU370897 |

| Q.2 | Italy 99.0% | 2020-12-15 | OU471040 |

| Q.3 | USA 99.0% | 2020-07-08 | ON129429 |

| Q.6 | France 92.0% | 2021-03-02 | ON300460 |

| Q.7 | France 86.0% | 2021-01-29 | ON442016 |

| L.2 | Netherlands 73.0% | 2020-03-23 | LR883305 |

| L.4 | USA 100.0% | 2020-06-29 | OK546730 |

| N.1 | USA 91.0% | 2020-03-25 | MT520277 |

| N.3 | Argentina 96.0% | 2020-04-17 | MW633892 |

| N.4 | Chile 92.0% | 2020-03-25 | MW365278 |

| N.6 | Chile 98.0% | 2020-02-16 | MW365092 |

| N.7 | Uruguay 100.0% | 2020-06-18 | MW298637 |

| N.8 | Kenya 94.0% | 2020-06-23 | OK510491 |

| N.9 | Brazil 96.0% | 2020-09-25 | MZ191508 |

| M.2 | Switzerland 90.0% | 2020-10-26 | OU009929 |

| P.1.7.1 | Peru 94.0% | 2021-02-07 | OK594577 |

| P.1.13 | USA 100.0% | 2021-02-24 | OL522465 |

| P.2 | Brazil 58.0% | 2020-04-13 | ON148325 |

| P.3 | Philippines 83.0% | 2021-01-08 | OL989074 |

| P.7 | Brazil 71.0% | 2020-07-01 | ON148327 |

Based on the sampling locations (consistent with the most common country, but accurate to specific cities) of each lineage sequence in Table 1, combined with the time when the lineage was first discovered, we obtained data on climatic conditions at the time each lineage was first discovered. The meteorological parameters include Temperature at 2 meters, Specific humidity at 2 meters, Precipitation corrected, Wind speed at 10 meters, and All sky surface shortwave Downward irradiance. The daily data for the above parameters were collected from the NASA website (https://

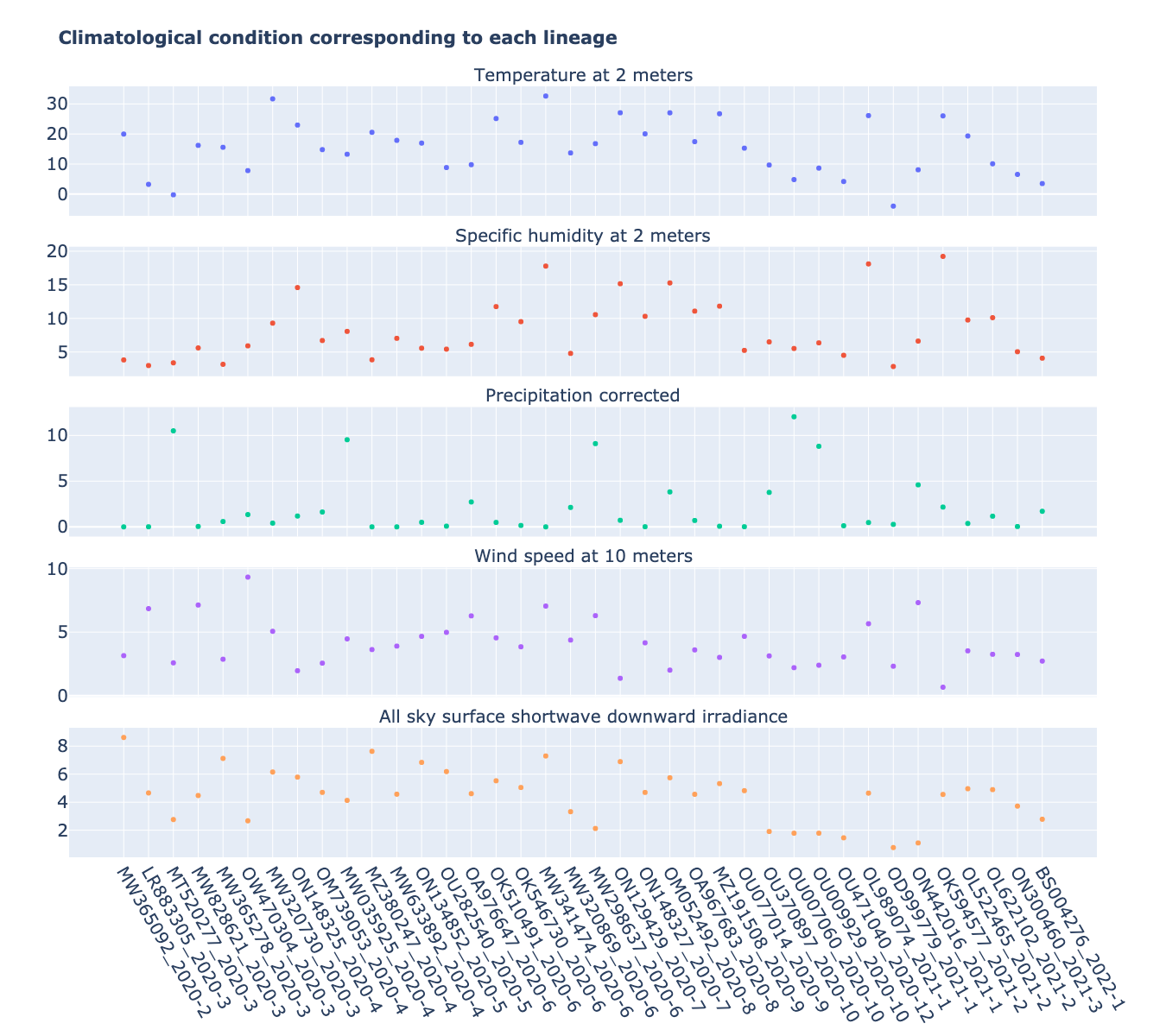

Figure 2:Climatic conditions of each lineage in most common country at the time of first detection. The climate factors involved include Temperature at 2 meters (C), Specific humidity at 2 meters (g/kg), Precipitation corrected (mm/day), Wind speed at 10 meters (m/s), and All sky surface shortwave downward irradiance .

Although the selection of samples was based on the phylogenetic cluster of lineage and transmission, most of the sites involved represent different meteorological conditions. As shown in Figure 2, the 38 samples involved temperatures ranging from -4 C to 32.6 C, with an average temperature of 15.3 C. The Specific humidity ranged from 2.9 g/kg to 19.2 g/kg with an average of 8.3 g/kg. The variability of Wind speed and All sky surface shortwave downward irradiance was relatively small across samples compared to other parameters. The Wind speed ranged from 0.7 m/s to 9.3 m/s with an average of 4.0 m/s, and All sky surface shortwave downward irradiance ranged from 0.8 kW-hr/m2/day to 8.6 kW-hr/m2/day with an average of 4.5 kW-hr/m2/day. In contrast to the other parameters, 75% of the cities involved receive less than 2.2 mm of precipitation per day, and only 5 cities have more than 5 mm of precipitation per day. The minimum precipitation is 0 mm/day, the maximum precipitation is 12 mm/day, and the average value is 2.1 mm/day.

Results¶

In this section, we describe the results obtained on our dataset (see Data section) using our new algorithm (see Method section).

The size of the sliding window and the advanced step for the sliding window play an important role in the analysis. We restricted our conditions to certain values. For comparison, we applied five combinations of parameters (window size and step size) to the same dataset. These include the choice of different window sizes (20bp, 50bp, 200bp) and step sizes (10bp, 50bp, 200bp). These combinations of window sizes and steps provide an opportunity to have three different movement strategies (overlapping, non-overlapping, with gaps). Here we fixed the pair (window size, step size) at some values (20, 10), (20, 50), (50, 50), (200, 50) and (200, 200).

- Robinson and Foulds baseline and bootstrap threshold: the phylogenetic trees constructed in each sliding window are compared to the climatic trees using the Robinson and Foulds topological distance (the RF distance). We defined the value of the RF distance obtained for regions without any mutations as the baseline. Although different sample sizes and sample sequence characteristics can cause differences in the baseline, however, regions without any mutation are often accompanied by very low bootstrap values. Using the distribution of bootstrap values and combining it with validation of alignment visualization, we confirmed that the RF baseline value in this study was 50, and the bootstrap values corresponding to this baseline were smaller than 10.

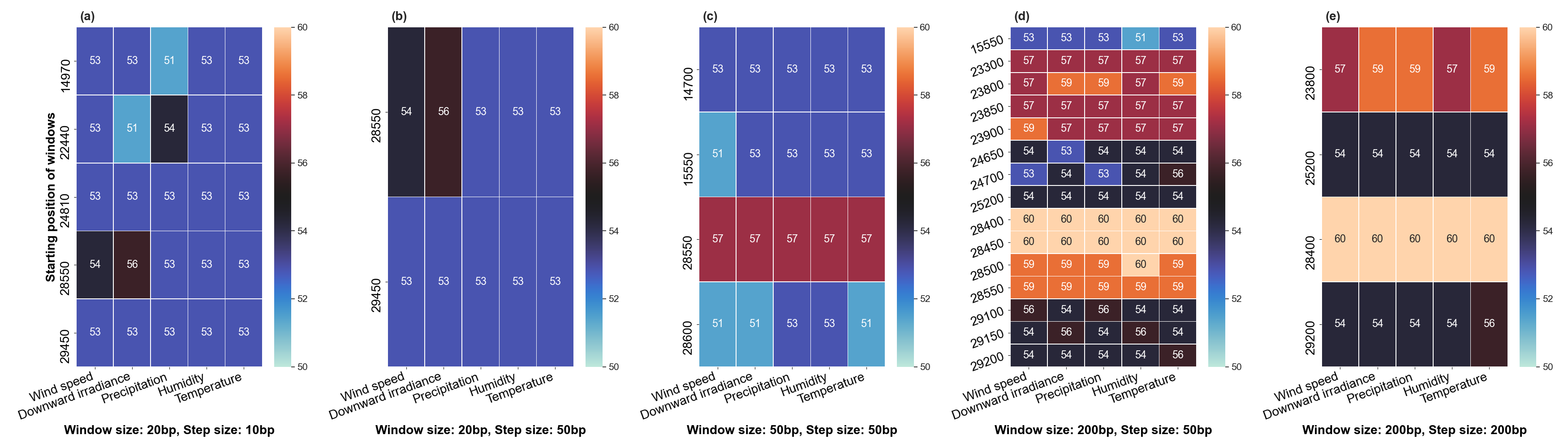

- Sliding window: the implementation of sliding window technology with bootstrap threshold provides a more accurate identification of regions with high gene mutation rates. Figure 3 shows the general pattern of the RF distance changes over alignment windows with different climate conditions on bootstrap values greater than 10. The trend of RF values variation under different climatic conditions does not vary much throughout this whole sequence sliding window scan, which may be related to the correlation between climatic factors (Wind Speed, Downward Irradiance, Precipitation, Humidity, Temperature). Windows starting from or containing position (28550bp) were screened in all five scans for different combinations of window size and step size. The window formed from position 29200bp to position 29470bp is screened out in all four scans except for the combination of 50bp window size with 50bp step size. As Figure 3 shows, if there are gaps in the scan (window size: 20bp, step size: 50bp), some potential mutation windows are not screened compared to other movement strategies because the sequences of the gap part are not computed by the algorithm. In addition, when the window size is small, the capture of the window mutation signal becomes more sensitive, especially when the number of samples is small. At this time, a single base change in a single sequence can cause a change in the value of the RF distance. Therefore, high quality sequencing data is required to prevent errors caused by ambiguous characters (N in nucleotide) on the RF distance values. In cases where a larger window size (200bp) is selected, the overlapping movement strategy (window size: 200bp, step size: 50bp) allows the signal of base mutations to be repeatedly verified and enhanced in adjacent window scans compared to the non-overlapping strategy (window size: 200bp, step size: 200bp). In this situation, the range of the RF distance values is relatively large, and the number of windows eventually screened is relatively greater. Due to the small number of the SARS-CoV-2 lineages sequences that we analyzed in this study, we chose to scan the alignment sequences with a larger window and overlapping movement strategy for further analysis (window size: 200bp, step size: 50bp).

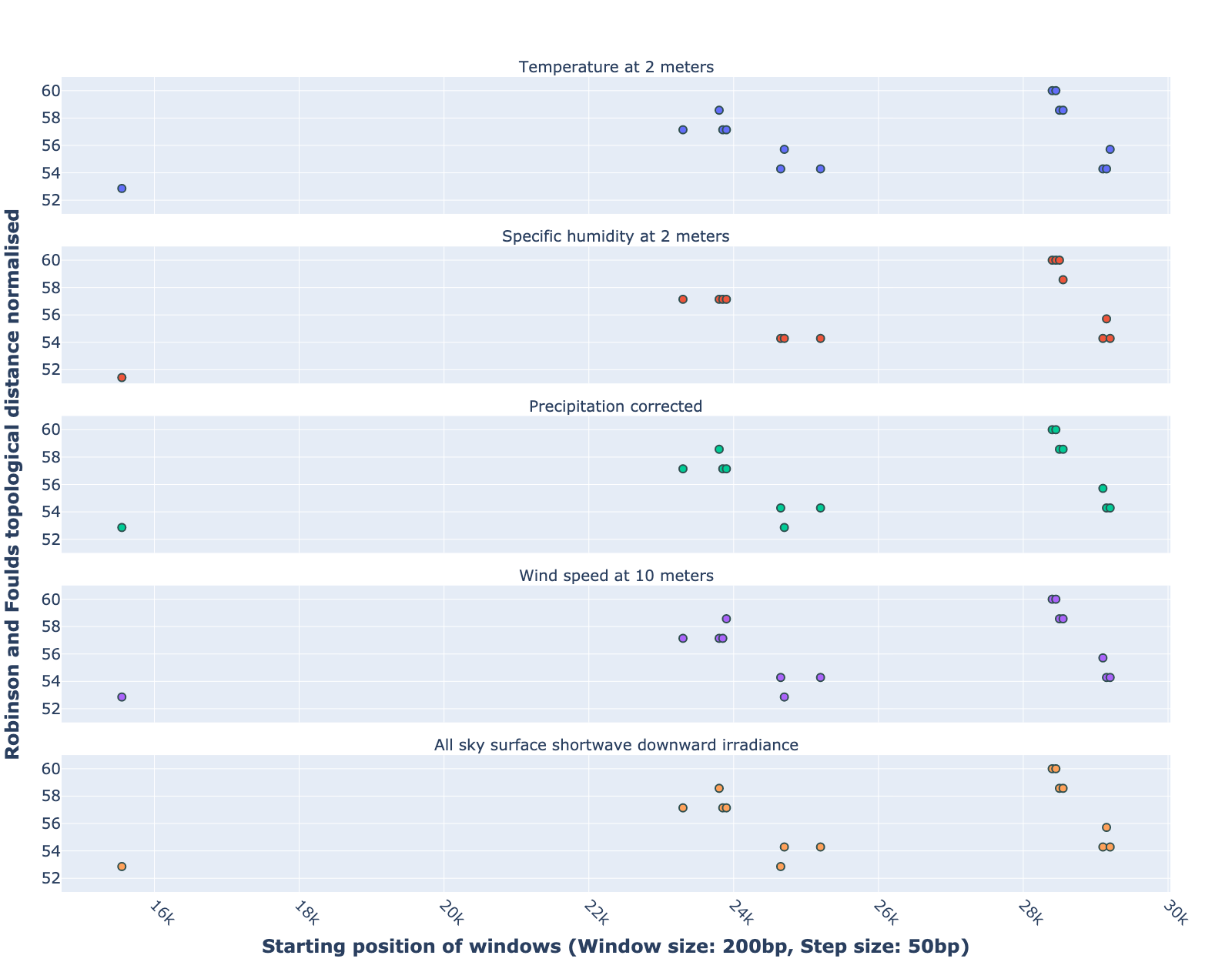

- Comparaison between genetic trees and climatic trees: the RF distance quantified the difference between a phylogenetic tree constructed in specific sliding windows and a climatic tree constructed in corresponding climatic data. Relatively low RF distance values represent relatively more similarity between the phylogenetic tree and the climatic tree. With our algorithm based on the sliding window technique, regions with high mutation rates can be identified (Fig 4). Subsequently, we compare the RF values of these regions. In cases where there is a correlation between the occurrence of mutations and the climate factors studied, the regions with relatively low RF distance values (the alignment position of 15550bp – 15600bp and 24650bp-24750bp) are more likely to be correlated with climate factors than the other loci screened for mutations.

Figure 3:Heatmap of Robinson and Foulds topological distance over alignment windows. Five different combinations of parameters were applied (a) window size = 20bp and step size = 10bp; (b) window size = 20bp and step size = 50bp; (c) window size = 50bp and step size = 50bp; (d) window size = 200bp and step size = 50bp; and (e) window size = 200bp and step size = 200bp. Robinson and Foulds topological distance was used to quantify the distance between a phylogenetic tree constructed in certain sliding windows and a climatic tree constructed in corresponding climatic data (wind speed, downward irradiance, precipitation, humidity, temperature).

Figure 4:Robinson and Foulds topological distance normalized changes over the alignment windows. Multiple phylogenetic analyses were performed using a sliding window (window size = 200 bp and step size = 50 bp). Phylogenetic reconstruction was repeated considering only data within a window that moved along the alignment in steps. The RF normalized topological distance was used to quantify the distance between the phylogenetic tree constructed in each sliding window and the climate tree constructed in the corresponding climate data (Wind speed, Downward irradiance, Precipitation, Humidity, Temperature). Only regions with high genetic mutation rates were marked in the figure.

In addition, we can state that we have made an effort to make our tool as independent as possible of the input data and parameters. Our pipeline can also be applied to phylogeographic studies of other species. In cases where it is determined (or assumed) that the occurrence of a mutation is associated with certain geographic factors, our pipeline can help to highlight mutant regions and specific mutant regions within them that are more likely to be associated with that geographic parameter. Our algorithm can provide a reference for further biological studies.

Conclusions and future work¶

In this paper, a bioinformatics pipeline for phylogeographic analysis is designed to help researchers better understand the distribution of viruses in specific regions using genetic and climate data. We propose a new algorithm called aPhylogeo Li et al., 2022 that allows the user to quickly and intuitively create trees from genetic and climate data. Using a sliding window, the algorithm finds specific regions on the viral genetic sequences that can be correlated to the climatic conditions of the region. To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind that incorporates climate data into this type of study. It aims to help the scientific community by facilitating research in the field of phylogeography. Our solution runs on Windows®, MacOS X® and GNU/Linux and the code is freely available to researchers and collaborators on GitHub (https://

As a future work on the project, we plan to incorporate the following additional features:

- We can handle large amounts of data, especially when considering many countries and longer time periods (dates). In addition, since the size of the sliding window and the forward step play an important role in the analysis, we need to perform several tests to choose the best combination of parameters. In this case, it is important to provide the faster performance of this solution, and we plan to adapt the code to parallelize the computations. In addition, we intend to use the resources of Compute Canada and Compute Quebec for these high load calculations.

- To enable further analysis of this topic, it would be interesting to relate the results obtained, especially the values obtained from the best positions of the multiple sequence alignments, to the dimensional structure of the proteins, or to the map of the selective pressure exerted on the indicated alignment fragments.

- We can envisage a study that would consist in selecting only different phenotypes of a single species, for example,

Homo Sapiens, in different geographical locations. In this case, we would have to consider a larger geographical area in order to significantly increase the variation of the selected climatic parameters. This type of research would consist in observing the evolution of the genes of the selected species according to different climatic parameters. - We intend to develop a website that can help biologists, ecologists and other interested professionals to perform calculations in their phylogeography projects faster and easier. We plan to create a user-friendly interface with the input of the necessary initial parameters and the possibility to save the results (for example, by sending them to an email). These results will include calculated parameters and visualizations.

The authors thank SciPy conference and reviewers for their valuable comments on this paper. This work was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the University of Sherbrooke grant.

Copyright © 2022 Koshkarov et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

- bp

- base pairs

- MSA

- multiple sequence alignment

- RF

- Robinson and Foulds

- SARS-CoV-2

- severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- VOC

- variants of concern

- WHO

- World Health Organization

- Cascella, M., Rajnik, M., Aleem, A., Dulebohn, S. C., & Di Napoli, R. (2022). Features, evaluation, and treatment of coronavirus (COVID-19). Statpearls [Internet].

- Lin, K., Fong, D. Y.-T., Zhu, B., & Karlberg, J. (2006). Environmental factors on the SARS epidemic: air temperature, passage of time and multiplicative effect of hospital infection. Epidemiology & Infection, 134(2), 223–230. 10.1017/S0950268805005054

- Oliveiros, B., Caramelo, L., Ferreira, N. C., & Caramelo, F. (2020). Role of temperature and humidity in the modulation of the doubling time of COVID-19 cases. MedRxiv. 10.1101/2020.03.05.20031872

- Sobral, M. F. F., Duarte, G. B., da Penha Sobral, A. I. G., Marinho, M. L. M., & de Souza Melo, A. (2020). Association between climate variables and global transmission oF SARS-CoV-2. Science of The Total Environment, 729, 138997. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138997

- Sabarathinam, C., Mohan Viswanathan, P., Senapathi, V., Karuppannan, S., Samayamanthula, D. R., Gopalakrishnan, G., Alagappan, R., & Bhattacharya, P. (2022). SARS-CoV-2 phase I transmission and mutability linked to the interplay of climatic variables: a global observation on the pandemic spread. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1–18. 10.1007/s11356-021-17481-8

- Chen, S., Prettner, K., Kuhn, M., Geldsetzer, P., Wang, C., Bärnighausen, T., & Bloom, D. E. (2021). Climate and the spread of COVID-19. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–6. 10.1038/s41598-021-87692-z

- Avise, J. C., & others. (2000). Phylogeography: the history and formation of species. Harvard University Press. 10.1093/icb/41.1.134

- Knowles, L. L., & Maddison, W. P. (2002). Statistical phylogeography. Molecular Ecology, 11(12), 2623–2635. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095702

- Nagylaki, T. (1992). Rate of evolution of a quantitative character. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 89(17), 8121–8124. 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8121

- Orr, M. R., & Smith, T. B. (1998). Ecology and speciation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 13(12), 502–506. 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01511-0

- Schluter, D. (2001). Ecology and the origin of species. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16(7), 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(01)02198-x

- Li, W., Luu, M.-L., Koshkarov, A., & Tahiri, N. (2022). aPhylogeo (version 1.0). doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6773603

- Robinson, D. F., & Foulds, L. R. (1981). Comparison of phylogenetic trees. Mathematical Biosciences, 53(1–2), 131–147. 10.1016/0025-5564(81)90043-2

- Edgar, R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics, 5(1), 1–19. 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113

- Felsenstein, J. (2005). PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package) version 3.6. Distributed by the author. Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle.