Zamba: Computer vision for wildlife conservation

Abstract¶

Camera traps are indispensable tools for wildlife conservation, but the vast volume of data they generate creates a significant bottleneck in manual processing. We present Zamba, an open-source Python package that leverages machine learning to streamline camera trap data analysis. Unlike most existing tools that support only image data, Zamba enables species classification for both still images and videos, as well as depth estimation from videos. It also supports custom model training on user-provided data, allowing adaptation to new species and geographic regions not covered by pretrained models. Zamba powers Zamba Cloud, a no-code web application that makes these capabilities accessible to non-programmers. By enabling conservationists to efficiently analyze large datasets and train models tailored to their specific ecological contexts, Zamba advances wildlife monitoring, research, and evidence-based conservation decision-making.

1Introduction¶

Camera traps are automated camera systems typically triggered by motion, heat, or timers Burton et al., 2015. They are a widely used tool for wildlife monitoring in both research and conservation. However, they generate an immense volume of image and video data due to the nature of the data collection and scale of their deployment. It takes the valuable time of teams of experts, or thousands of citizen scientists, to manually process this data and identify videos and images of interest Arandjelovic et al., 2024.

Automated computer vision systems offer a natural solution to assist with this data processing. Yet, two key gaps remain in the ecosystem for wildlife camera trap data. First, available domain-specific tools only support processing image data, not video Vélez et al., 2022, and it is not computationally feasible to predict on all frames in a video as if they were images. Moreover, models that process video natively can leverage inter-frame information—such as motion—that is otherwise lost. Second, pretrained models fail to capture the wide range of environments and use cases for which camera traps are deployed. Wildlife monitoring projects vary widely in habitat, focal species, deployment context, and taxonomic resolution, necessitating adaptable models that can be fine-tuned to specific contexts.

We present Zamba DrivenData et al., 2022, an open source Python package for using machine learning to process camera trap data. Zamba supports species classification for both videos and still images. Zamba also supports custom model training on user-provided camera trap data containing new species and new geographies not in the included pretrained models. In addition, Zamba includes inference-only video processing pipelines for depth estimation. Zamba also underlies Zamba Cloud, which is an accessible no-code web application that runs the python package on managed cloud resources. Zamba Cloud bridges a critical gap between the technical feasibility of training models and the practical ability for conservationists — who are often not programmers — to use them.

By enabling conservationists to efficiently process large datasets and train custom models suited to their unique ecological contexts and research questions, Zamba accelerates wildlife monitoring, research, and evidence-based conservation decision-making.

This paper provides an overview of Zamba’s contributions to the conservation community and details its underlying methodology. The motivation section illustrates the value of camera trap data for conservation efforts as well as the current bottlenecks. The development section reviews Zamba’s history. The following three sections detail the methods and performance for the video species classification, image species classification, and depth estimation models. We then discuss how Zamba Cloud provides an accessible no-code way to access Zamba’s classification capabilities. The discussion section concludes with guidance on common workflows.

2Motivation¶

Camera traps hold immense potential for conservationists as they are a noninvasive way of monitoring wildlife Rovero & Kays, 2021. They enable the measurement of species occupancy Tobler et al., 2015, relative Sollmann et al., 2013 or absolute abundance Howe et al., 2017, population trends over time O’Brien et al., 2019, patterns in animal behavior Caravaggi et al., 2017Vélez et al., 2022, and more. They are also one of the few tools for monitoring multiple species simultaneously Bessone et al., 2020.

As simple sensors, camera traps do not automatically label or filter the species they observe. Manual review and labeling represent a critical bottleneck, consuming vast amounts of resources that could otherwise support direct conservation actions Green et al., 2020Arandjelovic et al., 2024.

One of the most common needs is filtering out “blank” images and videos, i.e., those that do not contain an animal but rather were a false trigger, potentially caused by wind, rain, or changes in light. These “blanks” account for up to 70% of captured images Beery et al., 2019 in some datasets. Estimating animal distances in camera trap footage currently entails an extremely manual, time-intensive process. Automated distance extraction is estimated to be 21 times faster than manual labelling Haucke et al., 2022.

While more and more conservation organizations and researchers are collecting and storing camera trap data, many are not yet able to effectively use that data for decision-making. The people-power needed to view and annotate camera trap data is prohibitively expensive in terms of time and money, which results in organizations not using camera traps; data accumulating on hard drives; or long delays in turn-around while teams sift through thousands of incoming images and videos every month.

Machine learning (ML) models have shown significant promise in automating species identification from camera trap imagery Vélez et al., 2022. Several software tools that leverage ML have gained widespread adoption in recent years, including MegaDetector Beery et al., 2019, Wildlife Insights Ahumada et al., 2019, and Addax AI (formerly EcoAssist) Lunteren, 2023. These tools have advanced the application of pretrained computer vision models for animal detection and species classification particularly for camera trap image data.

Accurate, accessible, and automated species detection enables improved monitoring of animal populations and evaluation of conservation impacts on species abundance. Faster processing of camera trap data allows conservationists to conduct these assessments in weeks instead of years. This not only supports timely evaluations and interventions—allowing for adaptive management if efforts are not proving effective—but also enables the collection of more data from a broader range of locations. It also allows conservationists to direct their time toward more complex secondary analyses and making evidence-based conservation decisions.

3Development history¶

Zamba’s development has its origins in online machine learning challenges hosted by DrivenData in partnership with wildlife conservation experts—in particular from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI-EVA). Machine learning competitions have proven effective at harnessing community-driven innovation and enabling the rapid testing of thousands of approaches to solving a problem Bull et al., 2016. Zamba, named after the word for “forest” in Lingala[1], was created to make these advances more accessible to ecologists and conservationists.

2017: Pri-matrix Factorization Challenge and Zamba v1

In the Pri-matrix Factorization Challenge DrivenData, 2017, hosted by DrivenData and MPI-EVA, over 320 participants competed to develop accurate species detection models for camera trap video data. The competition used a unique dataset created through the Chimp&See Zooniverse project Arandjelovic et al., 2024, where thousands of citizen scientists manually labeled camera trap videos. Their efforts produced nearly 2,000 hours of annotated footage from the Chimp&See database.[2] The winning algorithm achieved 96% accuracy in detecting wildlife presence and 99% average accuracy in classifying species across 23 label classes DrivenData, 2018 and formed the foundation of the initial version[3] of Zamba, available through a command-line interface (CLI).

2018: Zamba Cloud

Zamba was further developed into a web application—Zamba Cloud—to promote wider accessibility and adoption. Zamba Cloud enables users to run Zamba on high-performance, cloud-based infrastructure through an easy-to-use web interface.

2021: Zamba v2

Zamba underwent a major re-architecture to leverage recent advances in computer vision, released as Zamba v2.0.0. Its models were also retrained on an expanded dataset of 250,000 labeled camera trap videos.[4] This update also introduced support for fine-tuning custom models on videos and incorporated a smarter frame selection strategy using a newly trained machine learning model called MegadetectorLite.

2021: Deep Chimpact Challenge and depth estimation

DrivenData partnered again with the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation to host the Deep Chimpact: Depth Estimation for Wildlife Conservation challenge DrivenData, 2021. More than 300 participants competed to develop models for monocular depth estimation—inferring the distance between camera traps and wildlife appearing at various moments in video footage. In 2022, the second-place model from this challenge was integrated into Zamba as an inference module.

2024–2025: Species classification for images

In March 2025, species classification for images was added in Zamba v2.6.0 and Zamba Cloud. This major update, supported by the WILDLABS Awards 2024, focused on enabling non-programmer users to train custom image classification models through Zamba Cloud’s no-code interface. The work involved aggregating diverse image datasets, experimenting with model architectures, and training a robust base model spanning 178 taxonomic label classes.

4Classifying species in videos¶

Camera trap videos are especially valuable for researchers studying animal behavior, as they capture rich information including sounds, movements, tool use, and interactions between individuals Kalan et al., 2019McCarthy et al., 2019Boesch et al., 2020. Videos also provide multiple views of the same individual, which can aid in identifying characteristics such as sex, size, and age Debetencourt et al., 2023McCarthy et al., 2020Arandjelovic et al., 2024. It can also enable individual identification, which is useful for capture-recapture studies Head et al., 2013.

However, video classification is more challenging than image classification. It demands more complex model architectures, increased computational resources such as graphics processing units (GPUs), and the ability to manage and process datasets often measured in terabytes. Zamba initially focused on videos in order to address the gap in the tooling ecosystem, as other automated species classification tools only supported still images.

In the sections that follow, we describe Zamba’s approach to species classification in videos. This includes the core methodologies, the available pretrained models and features, and performance metrics based on evaluation on a holdout set.

4.1Methods¶

4.1.1Training data¶

A large and diverse dataset is one of the most important factors influencing model accuracy for camera trap species classification. Zamba’s video models were trained on a dataset of 250,000 labeled camera trap videos. Half of this data was collected and annotated by trained ecologists, while the other half consists of high-confidence labels generated by citizen scientists through the Chimp&See platform. The training data comes from camera trap deployments in the following countries: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Guinea, Liberia, Mozambique, Nigeria, Republic of the Congo, Senegal, Tanzania, and Uganda.

Table 1:Locations included in the training data for the video species classification models

| Country | Location |

|---|---|

| Cameroon | Campo Ma'an National Park |

| Korup National Park | |

| Central African Republic | Dzanga-Sangha Protected Area |

| Côte d'Ivoire | GEPRENAF–Comoé |

| Djouroutou | |

| Taï National Park | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | Bili-Uele Protected Area |

| Salonga National Park | |

| Gabon | Loango National Park |

| Lopé National Park | |

| Guinea | Bakoun Classified Forest |

| Moyen-Bafing National Park | |

| Liberia | East Nimba Nature Reserve |

| Grebo-Krahn National Park | |

| Sapo National Park | |

| Mozambique | Gorongosa National Park |

| Nigeria | Gashaka-Gumti National Park |

| Republic of the Congo | Conkouati-Douli National Park |

| Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park | |

| Senegal | Kayan |

| Tanzania | Grumeti Game Reserve |

| Ugalla River National Park | |

| Uganda | Budongo Forest Reserve |

| Bwindi Forest National Park | |

| Ngogo, Kibale National Park |

A carefully considered train–test split strategy is critical for camera trap data. Because each camera remains fixed in place, many videos share identical backgrounds. Without careful splitting, models risk overfitting to site-specific visual features rather than generalizing to animal appearance. To address this, Zamba uses a site-aware split strategy, where all videos from a single camera location are placed entirely in either the training or test set.

Species labels in the dataset were standardized into 32 output classes[5] by manually grouping vernacular species names used in expert-labeled videos into a fixed set of target classes. This aggregation provided enough training examples per class while preserving a level of taxonomic granularity useful to most users out of the box. Although the 32 classes cover only a small portion of species studied in conservation research worldwide, Zamba also supports training custom models to cover additional species, habitats, and taxonomic ranks. See “Custom model training” for further discussion.

Table 2:Example vernacular names that were all mapped to the target class antelope_duiker

| antilope spp. | bongo | bushbuck | dikdik | duiker |

| eland | gazelle | grantsgazelle | hartebeest | impala |

| jentink's duiker | kudu | maxwell's duiker | nyala | ogilby's duiker |

| oribi | peter's duiker | red duiker | reedbuck | royal antelope |

| sable | sitatunga | thompsonsgazelle | topi | water chevrotain |

| waterbuck | wildebeest | white bellied duiker | yellow backed duiker | zebra duiker |

An additional training dataset of European wildlife was used to fine-tune a model specialized for European species. This dataset includes camera trap videos from Hintenteiche bei Biesenbrow, Germany Henrich et al., 2023.

4.1.2Classification model architecture¶

Zamba includes four pretrained species classification video models that implement one of the two architectures: time_distributed or slowfast.[6]

The time_distributed model architecture is based on EfficientNetV2 Tan & Le, 2021. EfficientNetV2 models are convolutional neural networks designed to jointly optimize model size and training speed. EfficientNetV2 is image-native, meaning it operates on each frame individually. The model is wrapped in a TimeDistributed layer fastai developers, 2021, which aggregates frame-level predictions into a single video-level prediction.

The slowfast model architecture uses the SlowFast Feichtenhofer et al., 2018 backbone for video classification. This model is named for its two parallel pathways: a slow pathway that processes low frame-rate inputs to capture spatial semantics, and a fast pathway that processes high frame-rate inputs to capture motion dynamics. As a video-native architecture, SlowFast models consider temporal relationships between frames, which can be especially valuable for detecting occluded animals that may only become apparent through movement.

Table 3 provides an overview of the models. The time_distributed and slowfast models are trained to classify 32 species or species groups common to Central and West Africa.[7] The european model is trained to classify 11 common species in Western Europe.[8] Each model has distinct relative strengths. For example, the slowfast model trained on African species may perform better for small-bodied animals like rodents than the time_distributed African species model. There is also a european model, fine-tuned from the time_distributed African model, that is trained on species from non-jungle ecologies in Western Europe. All models include a blank class to identify videos with no animals, but the dedicated blank_nonblank model may provide higher accuracy for blank detection alone.

Table 3:Summary of Zamba’s pretrained video models

| Model | Geography | Relative strengths | Architecture | Number of training videos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

blank_nonblank | Central Africa, West Africa, and Western Europe | Just blank detection, without species classification | Image-based TimeDistributedEfficientNet | ~263,000 |

time_distributed | Central and West Africa | Recommended species classification model for jungle ecologies | Image-based TimeDistributedEfficientNet | ~250,000 |

slowfast | Central and West Africa | Potentially better than time_distributed at small species detection | Video-native SlowFast | ~15,000 |

european | Western Europe | Trained on non-jungle ecologies | Finetuned time_distributed model | ~13,000 |

4.1.3Frame selection approach¶

One of the key technical challenges in working with camera trap videos—rather than still images—is frame selection. For datasets that motivated the development of Zamba, videos had a frame rate of 30 frames per second and were typically about 60 seconds long. Processing every frame as an image for such videos is computationally infeasible. Furthermore, animals may only be present in a minority of recorded frames, and selecting frames without the animal degrades the performance of downstream tasks like species classification and depth estimation.

Figure 1:Excerpts from two 60-second example videos in which animals appear only briefly. Each excerpt shows the first 5 seconds; the remaining 55 seconds contain an unoccupied field of view.

The default frame selection method currently used by Zamba is an efficient object detection model we developed called MegadetectorLite. This model evaluates each frame for the likelihood that it contains an animal. By default, the top 16 frames[9] with the highest detection probabilities are selected and passed to either the species classification or blank detection models.

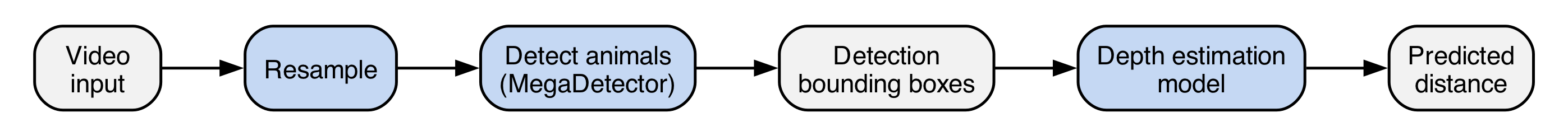

Figure 2:Flow diagram of the video species classification pipeline. Gray nodes indicate data and blue nodes indicate a processing step.

Because frame selection is an upstream task, it must be fast without sacrificing too much accuracy. Larger models tend to be more accurate but are slower to run. MegadetectorLite is based on the YOLOX architecture Ge et al., 2021 and was trained using a knowledge distillation approach Hinton et al., 2015 (also known as teacher–student training). It uses the predictions of the original MegaDetector Beery et al., 2019 as supervisory labels. MegaDetector itself is a highly accurate, but computationally intensive, object detection model trained specifically on camera trap imagery. While MegaDetector is used directly in Zamba’s image workflows, it is too slow for frame-by-frame inference in video processing. MegadetectorLite offers a more efficient alternative with a lightweight architecture.

We experimented with two YOLOX model variants (yolox-nano and yolox-tiny) and two input image sizes (416 and 640 pixels). We ultimately selected yolox-tiny with an input size of 640 pixels as the best tradeoff between speed and accuracy.

MegadetectorLite was trained on over 1 million frames. To improve detection of rare species—which have historically underperformed in automated systems—the training dataset was enriched with extra frames from videos featuring less frequently observed animals, including hyenas, leopards, aardvarks, reptiles, bats, giraffes, lions, cheetahs, and badgers.

4.2Results¶

4.2.1Pretrained model performance¶

Metrics for camera trap tasks are highly dataset-dependent and can vary widely depending on deployment context and class balance. Here, we report some illustrative evaluation metrics for Zamba’s pretrained models using holdout validation.

The holdout set comprises a random sample of labeled videos, selected on a transect-by-transect basis. That is, all videos from a given transect (camera location) are assigned entirely to either the training or holdout set. While not all use cases require this site-aware split, this is a stricter evaluation to performance on transects the model has never seen.

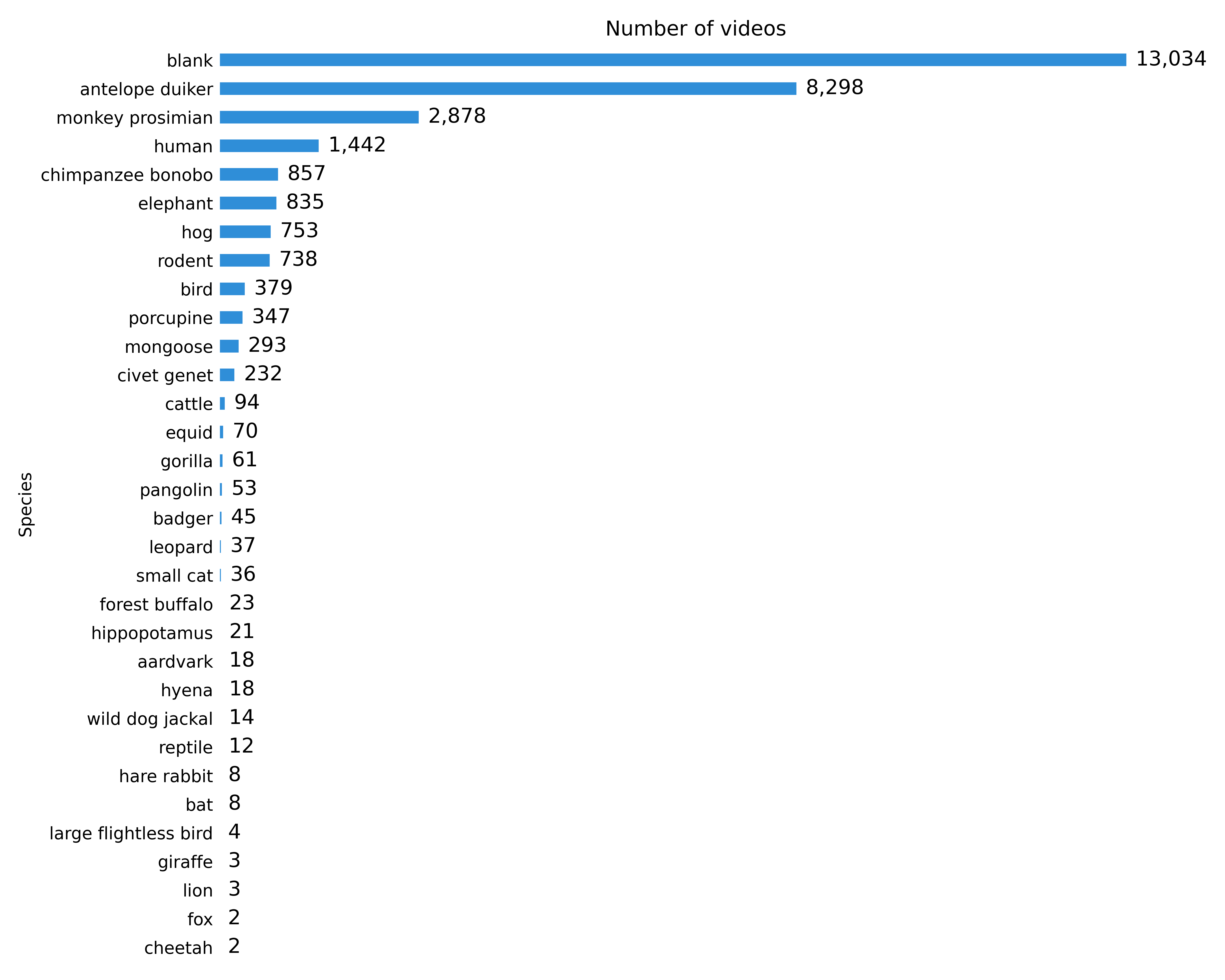

The holdout set includes data from all 14 countries in the training dataset, with country-level proportions roughly matching those of the complete set. Figure 3 shows the distribution of videos across 30 animal species, as well as a substantial number of blank videos and some containing humans.

Figure 3:Distribution of label classes in video model holdout set.

4.2.1.1Species classification¶

On the holdout set, African species time_distributed model achieves a top-1 accuracy[10] of 82% and a top-3 accuracy[11] of 94%. Performance varies across regions depending on species diversity. For example, in the limited sample of videos from Equatorial Guinea, only three species are represented. In this case, top-1 accuracy is 97%, significantly above the global average. In contrast, Ivory Coast videos contain 21 species, making classification more challenging; here, top-1 accuracy drops to 80%.

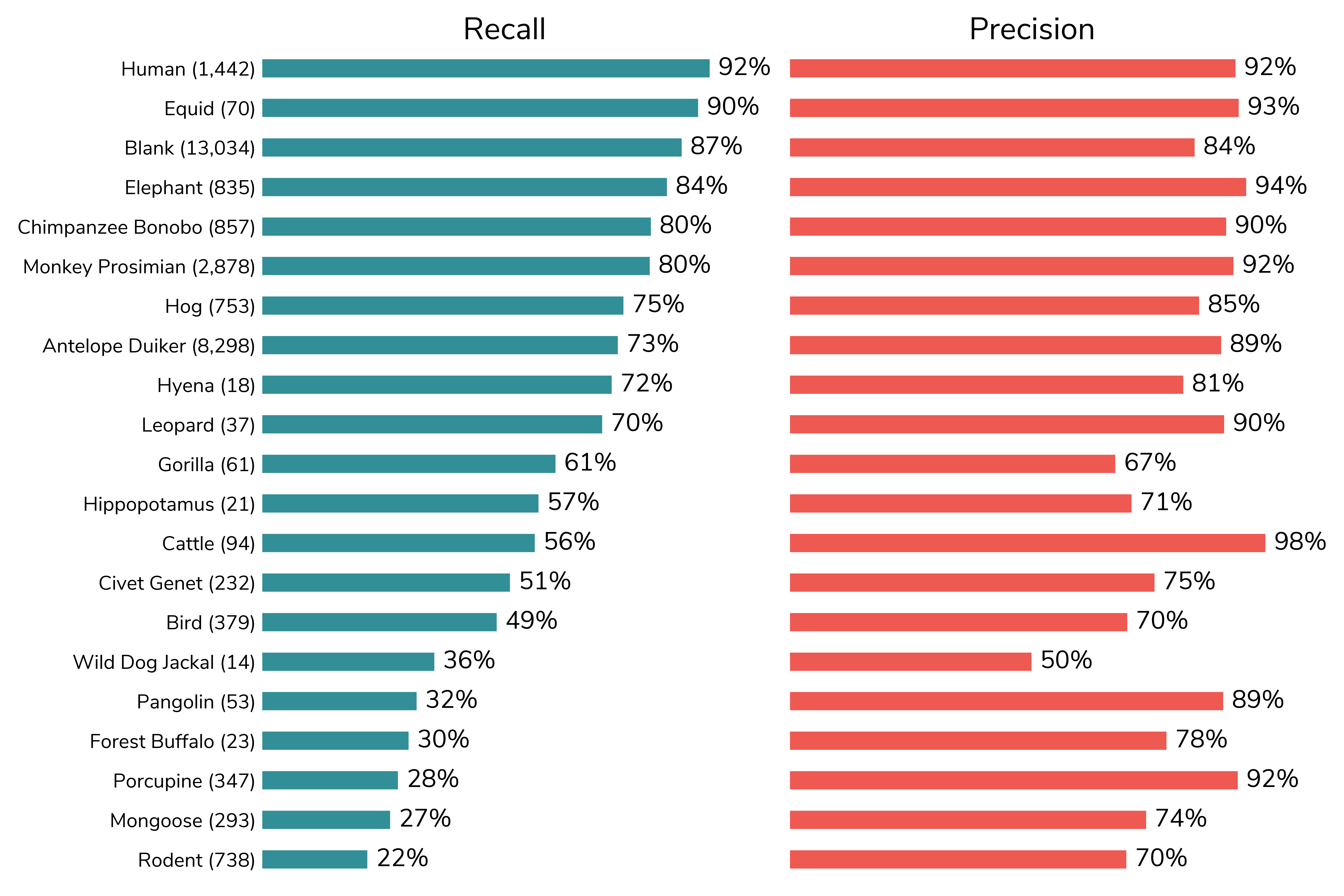

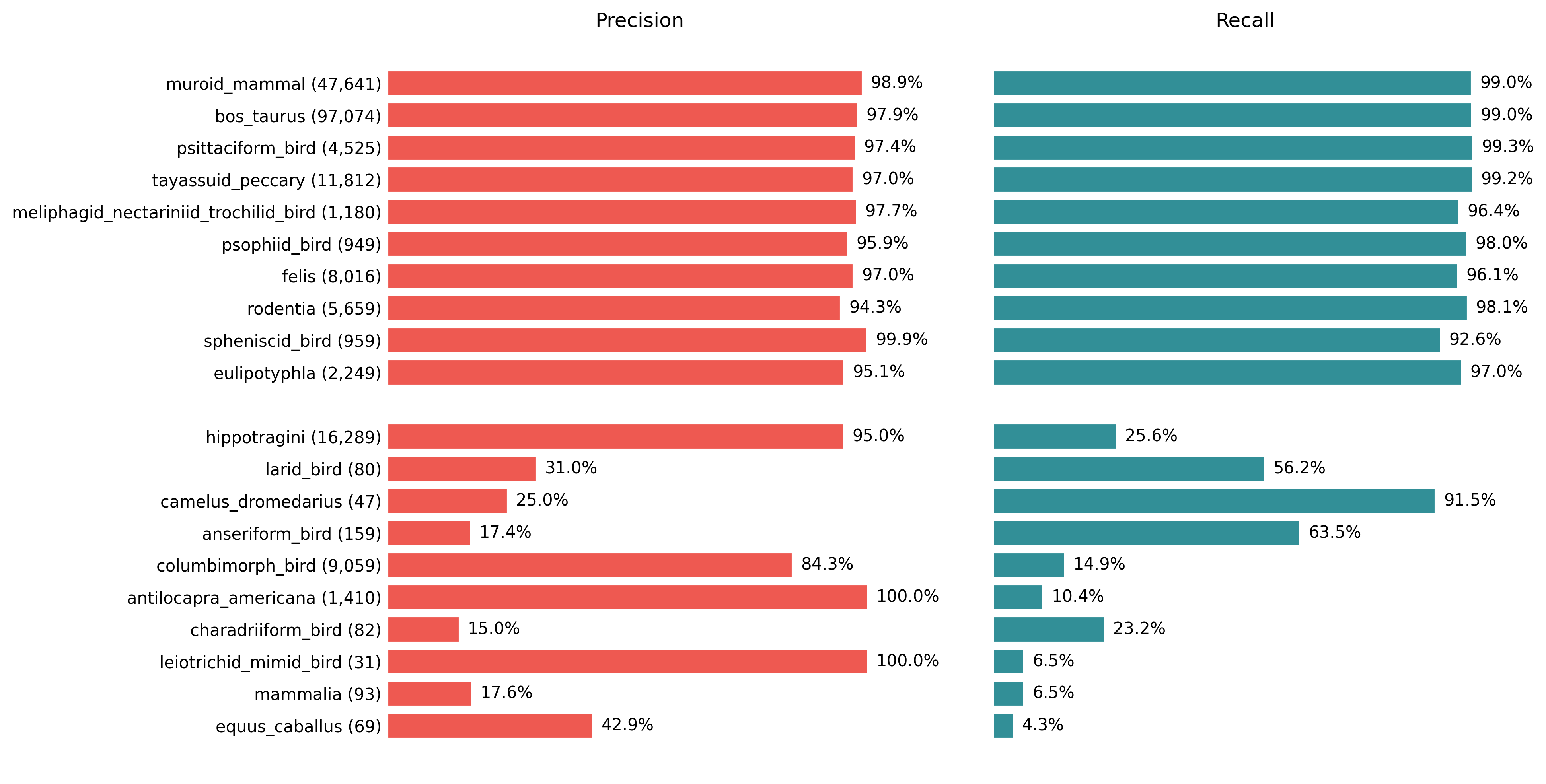

Figure 4 shows precision and recall by class for the holdout set. Eleven species with too few examples were excluded from this analysis. In general, recall tends to be higher for larger animals. However, even for species with lower recall, it is still feasible to use predicted probabilities to flag likely candidates for further review. For example, rodents have a recall of only 22%, but sorting videos by the model’s predicted probability for the “rodent” class remains a useful heuristic—even if other classes have higher probabilities predicted.

Figure 4:Precision and recall by class for the holdout set.

Model performance tends to be lower for:

Rare species with limited training data

Small-bodied animals, especially since the video models classify the entire frame without cropping around the subject

Heavily occluded or distant animals, or those only partially visible or present for just a few frames

Low-quality media, such as videos that are washed out or too dark

Because of a lack of comparable wildlife camera trap tools that perform species classificaiton for videos, it is difficult to provide a direct comparison to other results. Users are always encouraged to evaluate models on their own data. Additionally, Zamba supports fine-tuning custom models which can often be the best choice for achieving strong performance.

4.2.1.2Blank detection¶

Blank detection is an important feature in camera trap workflows due to the high prevalence of blank videos. In our holdout set, 42% of videos contained no animal activity. The blank_nonblank model achieved 87% recall (correctly identifies 11,288 of 13,034 blank videos) and 84% precision (13,507 videos predicted as blank, of which 11,288 were correct).

4.2.2Applications to out-of-domain data¶

While Zamba’s pretrained models are trained to predict specific classes for species from Africa and Western Europe, it can be possible to effectively apply them to out-of-domain data that includes geographies or species that the model has never seen. In DrivenData (2023), we show a case study using a dataset of 3,056 videos from New Zealand. Using the pretrained African species time_distributed model, the bird label correctly captures 77% of the takahē videos (recall) at 82% precision, which is particuarly notable since the takahē is a New-Zealand-native flightless bird that is not present in the African training data. However, other New Zealand-native birds like the weka are less successfully captured by the bird category (44% recall). Training custom models is recommended to achieve more accurate classification on new geographies and species.

4.2.3Configuration and customization¶

All Zamba workflows—inference, fine-tuning, and training—support an extensive range of configuration options. For instance, processed videos are resized to configurable size, by default 240x426 pixels. Higher resolution videos will lead to superior accuracy in prediction, but will use more memory and take longer to train or predict.

Frame selection is another key configurable option. In addition to the default MegadetectorLite method, users can choose from:

Evenly distributed frames

Early-biased frame sampling

Key frame extraction

Scene-change-based selection

The number of frames selected is also customizable (default: 16).

Configurations can be provided via command-line flags or through YAML-formatted configuration files.

4.2.4Custom model training¶

One of Zamba’s signature features is its support for training custom models. Custom models are primarily built by fine-tuning general-purpose species classifiers and can enhance performance in specific ecological contexts—even when classifying the same species. Custom models are also essential for extending classification to new species, new habitats, or label classes at different taxonomic ranks.

Zamba supports two fine-tuning scenarios based on label compatibility:

If the new training data uses a subset of the model’s existing classes, Zamba continues training with the existing classification head.

If the training data includes new or different label classes, Zamba automatically replaces the model’s classification head (i.e., the final neural network layer) before continuing training.

5Classifying species in images¶

While Zamba began with a focus on video data, the majority of camera trap users today collect still images. Images have several practical advantages: they require less storage space, use less battery life, and are faster to transfer, review, and process. Images are often sufficient for determining presence or absence of a particular species and can be used for distance sampling Haucke et al., 2022 as well to get to abundance estimates.

There are a number of machine learning tools for processing camera trap images Vélez et al., 2022. However, static pretrained models fail to capture the diversity in camera trap images and the range of environments in which camera traps are used around the globe.

Zamba’s extension into image support was motivated by the need to bring custom model training workflows to image-based data, building on the similar capabilities already developed for videos. The ability to train accurate models with a relatively small amount of labeled data is central to Zamba’s goal of enabling camera trap users to harness automated species classification for their unique datasets.

In the sections that follow, we outline the core methods Zamba employs for species classification in images, and present performance metrics for the general image classification model that forms the foundation for training custom models.

5.1Methods¶

5.1.1Cropping¶

Following the approach of Gadot et al. (2024), Zamba’s image classification pipeline first applies a species-agnostic object detection model to extract bounding box crops of detected animals. The image classification model then operates solely on these cropped regions, rather than processing the full-frame image.

For object detection, Zamba uses MegaDetector Beery et al., 2019, a widely adopted open-source model designed specifically for wildlife camera trap data. MegaDetector identifies animals, humans, and vehicles in camera trap imagery and is a standard component in many ecological processing pipelines Vélez et al., 2022. For additional technical details and performance evaluations of MegaDetector, see Vélez et al. (2022).

Figure 5:Flow diagram of the image species classification pipeline. Gray nodes indicate data and blue nodes indicate a processing step.

5.1.2Training data¶

Zamba’s pretrained image classification model was trained on over 15 million annotations from over 7 million images from the Labeled Information Library of Alexandria: Biology and Conservation (LILA BC) data repository Morris, 2017. Each annotation corresponds to a cropped image of an animal, extracted using bounding boxes generated by MegaDetector Beery et al., 2019.

To maximize geographic and ecological diversity, the training dataset aggregated 20 terrestrial camera trap datasets from LILA BC, representing a wide range of global habitats. (See Table 4 for a full list of datasets.) This broad coverage was designed to produce a versatile base model well-suited for fine-tuning to a wide variety of ecological contexts.

Table 4:Datasets from LILA BC included in training data

| Dataset | Geography | Count of original images | Count of cropped annotations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caltech Camera Traps Beery et al., 2018 | Southwestern United States | 59,205 | 96,724 |

| Channel Islands Camera Traps The Nature Conservancy, 2021 | California, United States | 125,369 | 239,472 |

| Desert Lion Camera Traps Desert Lion Conservation Project, 2024 | Namibia | 61,910 | 185,475 |

| ENA24-detection Yousif et al., 2019 | Eastern North America | 8,652 | 11,092 |

| Idaho Camera Traps Idaho Department of Fish and Game, 2021 | Idaho, United States | 338,706 | 1,072,912 |

| Island Conservation Camera Traps Island Conservation, 2020 | 7 islands around the world | 44,007 | 79,660 |

| Missouri Camera Traps Zhang et al., 2016 | Missouri, United States | 946 | 955 |

| North American Camera Trap Images Tabak et al., 2018 | United States | 2,705,394 | 7,426,839 |

| New Zealand Trailcams New Zealand Trailcams, 2024 | New Zealand | 2,109,592 | 2,794,859 |

| Orinoquia Camera Traps Vélez et al., 2022 | Colombia | 80,307 | 103,856 |

| Snapshot Safari 2024 Expansion Pardo et al., 2021 | Africa (multiple countries) | 836,522 | 1,949,366 |

| Snapshot Safari Camdeboo Pardo et al., 2021 | South Africa | 15,299 | 26,379 |

| Snapshot Safari Enonkishu Pardo et al., 2021 | Kenya | 9,049 | 37,252 |

| Snapshot Safari Karoo Pardo et al., 2021 | South Africa | 5,764 | 8,426 |

| Snapshot Safari Kgalagadi Pardo et al., 2021 | South Africa and Botswana | 2,060 | 2,938 |

| Snapshot Safari Kruger Pardo et al., 2021 | South Africa | 3,112 | 6,343 |

| Snapshot Safari Mountain Zebra Pardo et al., 2021 | South Africa | 5,535 | 9,333 |

| SWG Camera Traps Saola Working Group, 2021 | Vietnam and Laos | 87,309 | 100,677 |

| WCS Camera Traps Wildlife Conservation Society, 2019 | 12 countries | 523,897 | 920,471 |

| Wellington Camera Traps Anton et al., 2018 | New Zealand | 203,038 | 269,146 |

A key challenge in using data from these disparate sources was the lack of a unified taxonomy across datasets. Each dataset was collected independently, often for different research purposes, and the taxonomic granularity varies significantly. For example, some datasets label all birds under a generic “bird” class, while others distinguish specific bird species.

To address this, we reviewed 1,231 label classes across the source datasets and curated a unified taxonomy with 178 label classes. These classes span a variety of Linnaean taxonomic ranks, with each class having a minimum of 100 annotations to ensure sufficient training examples. As with the video models, these label classes represent a narrow subset of the wildlife of interest to conservationists. This model is intended to primarily serve as a base model for fine-tuning custom models, rather than serving as a general-purpose model that directly covers conservation use cases.

As with the video classification models, a split-aware strategy was used to create training, validation, and test sets. All data from a given camera location were assigned to the same split to avoid overfitting to background features and ensure generalizable model performance.

5.1.3Classification model architecture¶

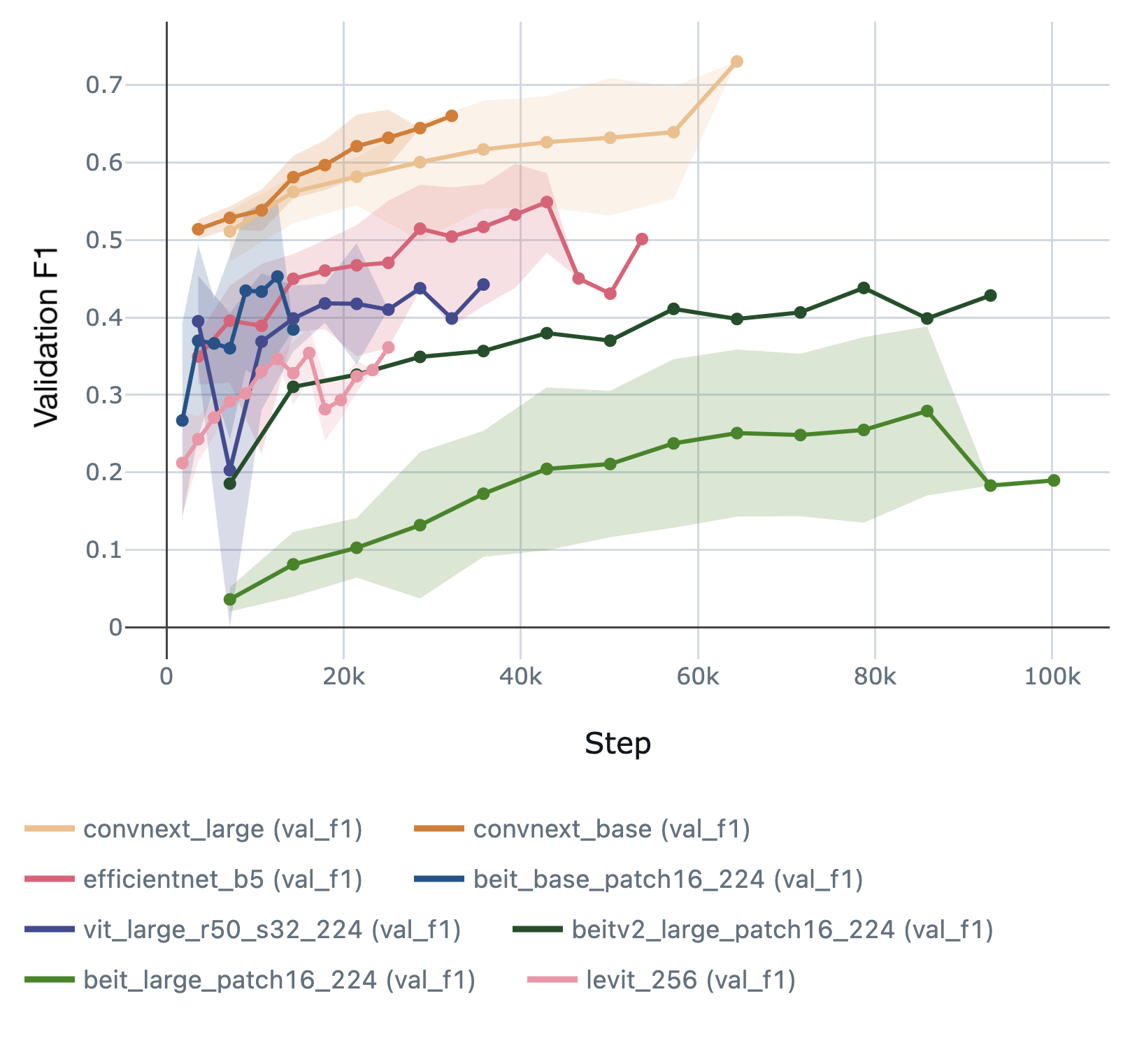

In order to select a backbone architecture, we evaluated several modern neural network architectures that post-date the commonly used backbones in most existing camera trap models. The candidate architectures included ConvNeXt, BEiT, EfficientNet, LeViT, and ViT.

Figure 6 shows run curves for the different backbone architectures we evaluated. Runs for ConvNeXt variants outperformed others, achieving greater accuracy with fewer training epochs. Based on these results, we chose ConvNeXt V2 base as the backbone.

Figure 6:Validation F1 training run curves for candidate model architectures. The filled band shows the min and max range across runs, and the line shows the average across runs.

The chosen ConvNeXt V2 base model contains 87.7 million parameters and operates on 224×224 pixel input crops. In Figure 6, its performance is represented by the dark orange curve.

5.2Results¶

5.2.1Pretrained model performance¶

As with videos, metrics for camera trap tasks are highly dataset-dependent and can vary widely based on deployment context and class balance. Here, we report some illustrative metrics for Zamba’s pretrained image model lila.science using holdout validation.

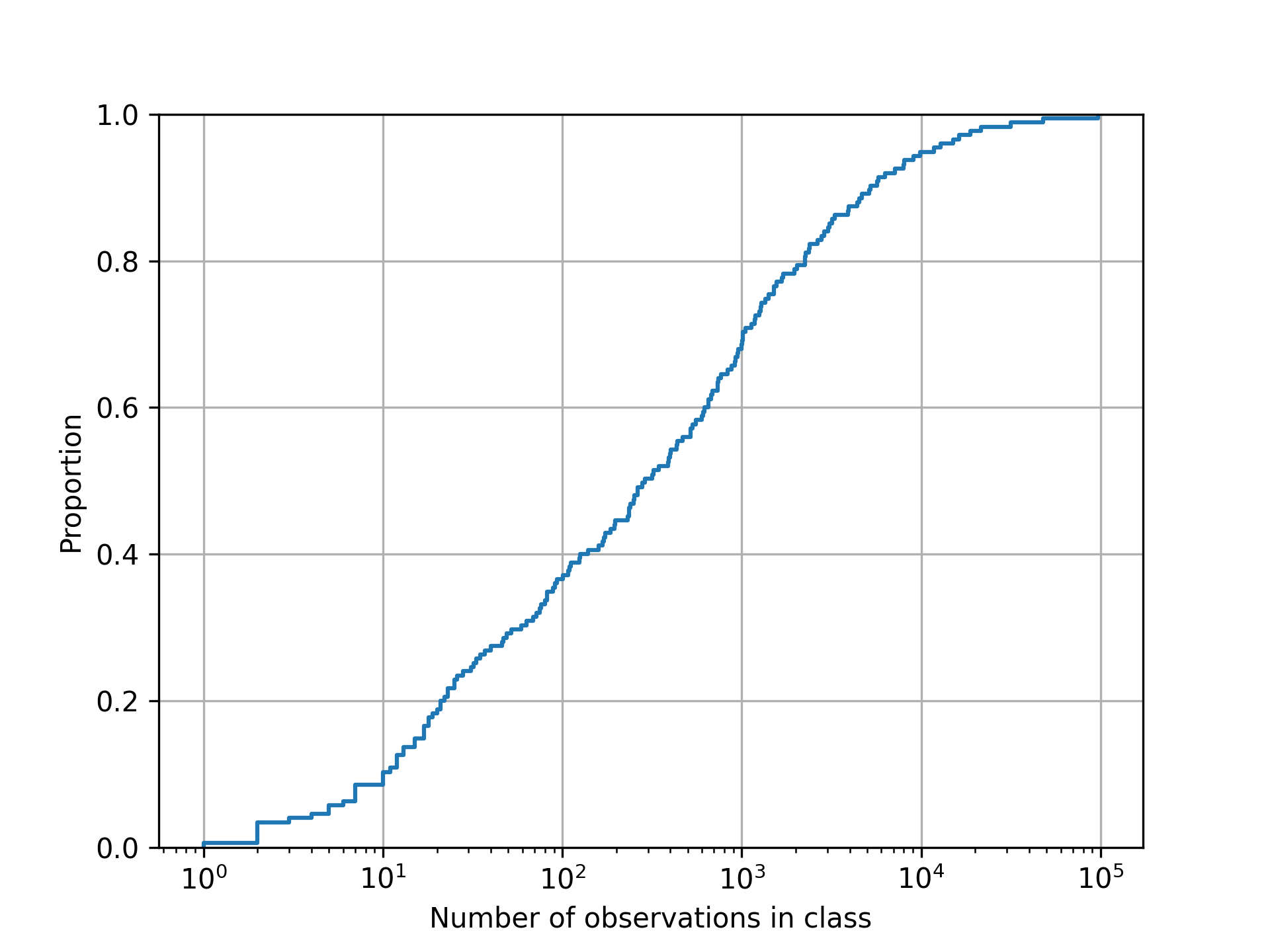

The holdout set reported here contains 449,263 randomly sampled observations held out from training. Splits were performed on a transect-by-transect basis[12] while ensuring at least one transect representing each label class is present in all splits. The holdout set is highly unbalanced, with a exponential-like distribution of class sizes. Figure 7 shows an empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) of the number of observations in each class.

Figure 7:ECDF of showing the distribution of class sizes. The curve shows the proportion of the label classes with up to the number of observations in the holdout set given by the x-axis value. Note that the x-axis is shown in log-scale.

On the holdout set, the lila.science model achieved 90% top-1 accuracy. Performance varies widely by label class, although the majority of label classes see relatively strong performance. Figure 7 shows the distribution of F1 scores across label classes for classes with at least 30 observations. Of those (133 classes), 40% (53 classes) have an F1 score of over 0.9 and 71% (94) have an F1 score of over 0.8.

Figure 8:Complementary ECDF of F1 score for label classes in the holdout set with at least 30 observations. The curve shows the count of label classes whose F1 score exceeds the value given by the x-axis.

Figure 9 shows the precision and recall scores for top 10 and bottom 10 label classes when ranked by F1 score. This shows that the model performs highly accurately on the top performing label classes. For the weakest label classes, there is a mix of strong-precision–weak-recall, weak-precision–strong-recall, or weak performance in both metrics. The weakest classes tend to be classes with the fewest observations in the test set (<100), although some classes with many observations like hippotragini and columbimorph_bird with thousands of test observations show relatively low recall scores. Cases of weak performance are often driven by confusion between phenotypically similar classes; for instance, observations involving types are birds are often predicted at different taxonomic granularity from the label.

Figure 9:Precision and recall values for a selection of label classes. The top half are the top 10 label classes ranked by F1 score, while the bottom half are the bottom 10 label classes ranked by F1 score. The parenthetical annotation gives the number of observations of that class.

For an indirect comparison[13], SpeciesNet, the model used by Wildlife Insights, report a 81.9% accuracy, 80.7 species-weighted-average F1 score, and 54.2 macro-averaged F1 score on a test dataset of 42,791 images with 101 label classesGadot et al., 2024. This comparison shows that Zamba’s pretrained model is in an approximate comparable range of performance as the published results of similar tools.

6Depth estimation for videos¶

Statistical models can be used to estimate animal abundance from camera trapping Gilbert et al., 2020. One such method is the distance sampling framework Haucke et al., 2022, which combines the frequency of animal sightings with the distance from the camera to each animal to estimate a species’ full population size Howe et al., 2017. In the following sections, we outline the training data, model architecture, and performance of Zamba’s depth estimation approach for videos.

6.1Methods¶

As discussed in the “Development History” section above, the Deep Chimpact machine learning challenge was held to develop and train models for performing depth estimation on monocular camera trap videos.

The top performing model from the second place ensemble[14] was integrated into Zamba as an inference-only module.[15] As no additional retraining was conducted, the below sections describe the competition data and results.

6.1.1Training data¶

Zamba’s depth estimation model was developed using a unique dataset of approximately 3,900 videos, created by research teams from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI-EVA) and the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation (WCF). Videos were from Taï National Park in Côte d’Ivoire and Moyen-Bafing National Park in the Republic of Guinea and captured six different species groups: bushbucks, chimpanzees, duikers, elephants, leopards, and monkeys.

Ground truth distances in the dataset were manually annotated with the aid of reference videos, which are recordings of field researchers walking away from each camera trap holding a sign up every meter to indicate how far they were from the camera. Such reference videos are a typical way to perform depth estimation for camera trap videos Haucke et al., 2022; however, they are time and resource intensive to record and to use in labeling.

Figure 10:A researcher in Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire holding up a sign at 5 meters away as part of a depth reference video. Image courtesy of Wild Chimpanzee Foundation.

Videos in the original dataset that included more than one animal were excluded as there was not a way in the labeled data to identify which distance label corresponded to which animal. This removed 18% of frames from the original Taï National Park dataset and 22% of frames from the original Moyen-Bafing dataset.

Data was split evenly into a training dataset and a test dataset. Each site was either entirely in the train set or the test set, so all backgrounds used to evaluate submissions were new to the model.

Table 5:Counts per location for the final dataset used in the competition

| Park | Train set | Test set |

|---|---|---|

| Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire | 530 videos 4,173 frames | 508 videos 3,802 frames |

| Moyen-Bafing National Park, Guinea | 1,542 videos 11,056 frames | 1,328 videos 8,130 frames |

Table 6:Distribution of species labels in the train and test sets

| Species | Train videos | Train frames | Test videos | Test frames |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| duiker | 744 | 6,805 | 695 | 5,718 |

| buckbuck | 261 | 3,550 | 230 | 2,603 |

| chimpanzee | 304 | 2,876 | 249 | 2,150 |

| monkey | 738 | 1,757 | 642 | 1,279 |

| leopard | 27 | 230 | 20 | 162 |

| elephant | 1 | 11 | 1 | 20 |

The videos ranged between 5 seconds and 1 minute long. Each annotation includes a timestamp in seconds since the start of the video and the ground truth distance in meters.

Example rows of depth estimation annotations

| video_id | time | distance |

|---|---|---|

| zxsz.mp4 | 0 | 7.0 |

| zxsz.mp4 | 2 | 8.0 |

| zxsz.mp4 | 4 | 10.0 |

6.1.2No references videos¶

The depth estimation model was not trained using any reference videos directly. The model was instead required to learn purely from monocular images and the distance ground truth labels. This is a more challenging task but enables more complete automation of the workflow.

6.1.3Model architecture¶

The depth estimation pipeline applies the following steps. First, videos are resampled to one frame per second to match the training dataset. Next, an object detection model is used on each frame to find frames with animals in them. The object detection model used is MegadetectorLite. Then, the depth estimation model estimates distance between the animal and the camera for each frame.[16]

Figure 11:Flow diagram of the video depth estimation pipeline. Gray nodes indicate data and blue nodes indicate a processing step.

The depth estimation model uses an EfficientNetV2 Tan & Le, 2021 backbone and the output is a scalar estimated distance in meters between the animal and the camera. The inputs to the model are 5 frames stacked channelwise, where the frames are chronological and the middle frame corresponds to the present frame for which the depth estimation is made. The frames are downsampled to 270x480. The model was trained with heavy augmentations for 80 epochs with a batch size of 32, AdamW optimizer, and CosineAnnealingLR scheduler with a period of 25 epochs.[17]

6.2Results¶

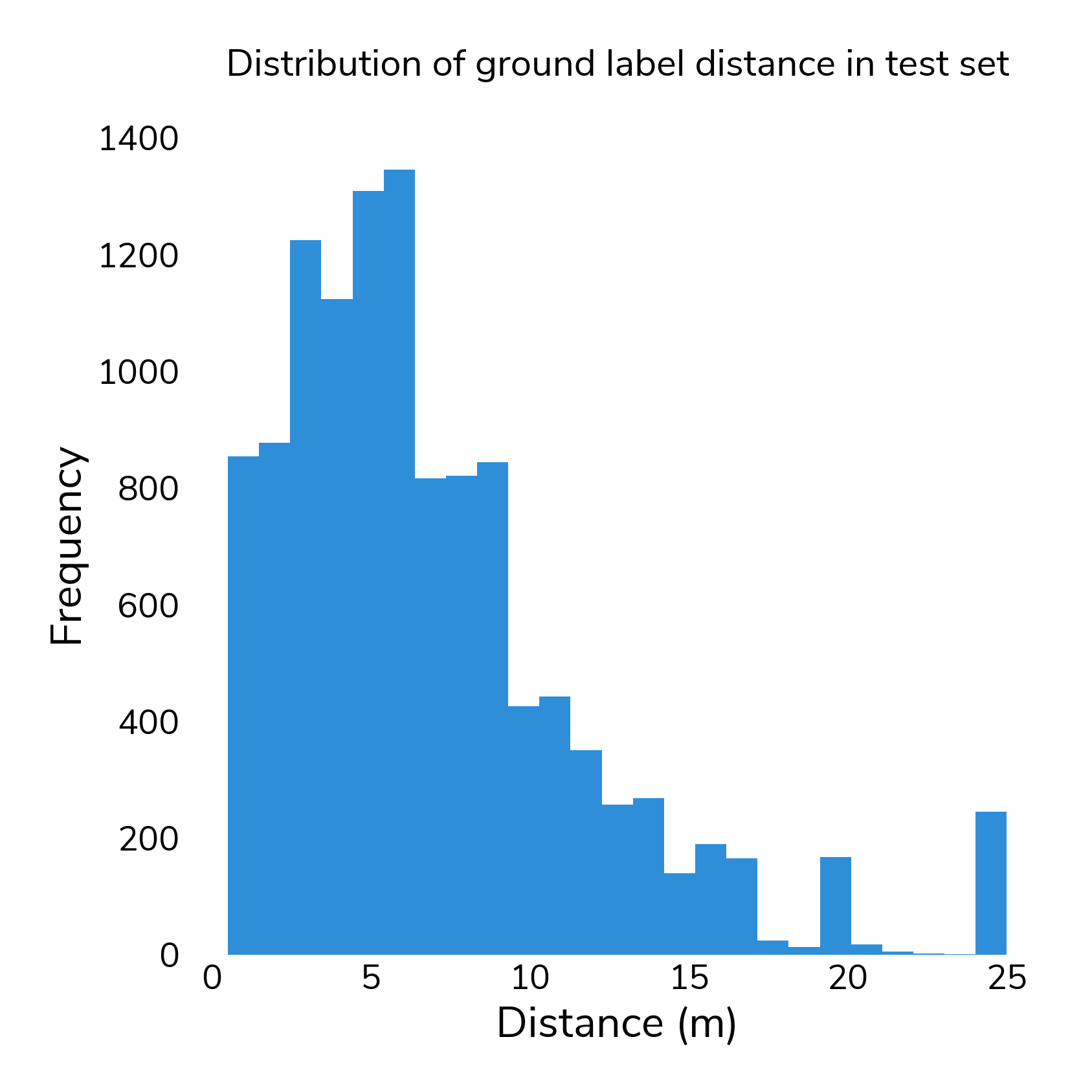

Model performance is reported for the test set of nearly 12,000 frames described above. The distribution of distances is shown in Figure 12. Nearly half (45%) of frames had a labeled distance of 5 meters or less and 80% of frames had a labeled distance of 10 meters or less.

Figure 12:Distribution of distances in the depth estimation test set

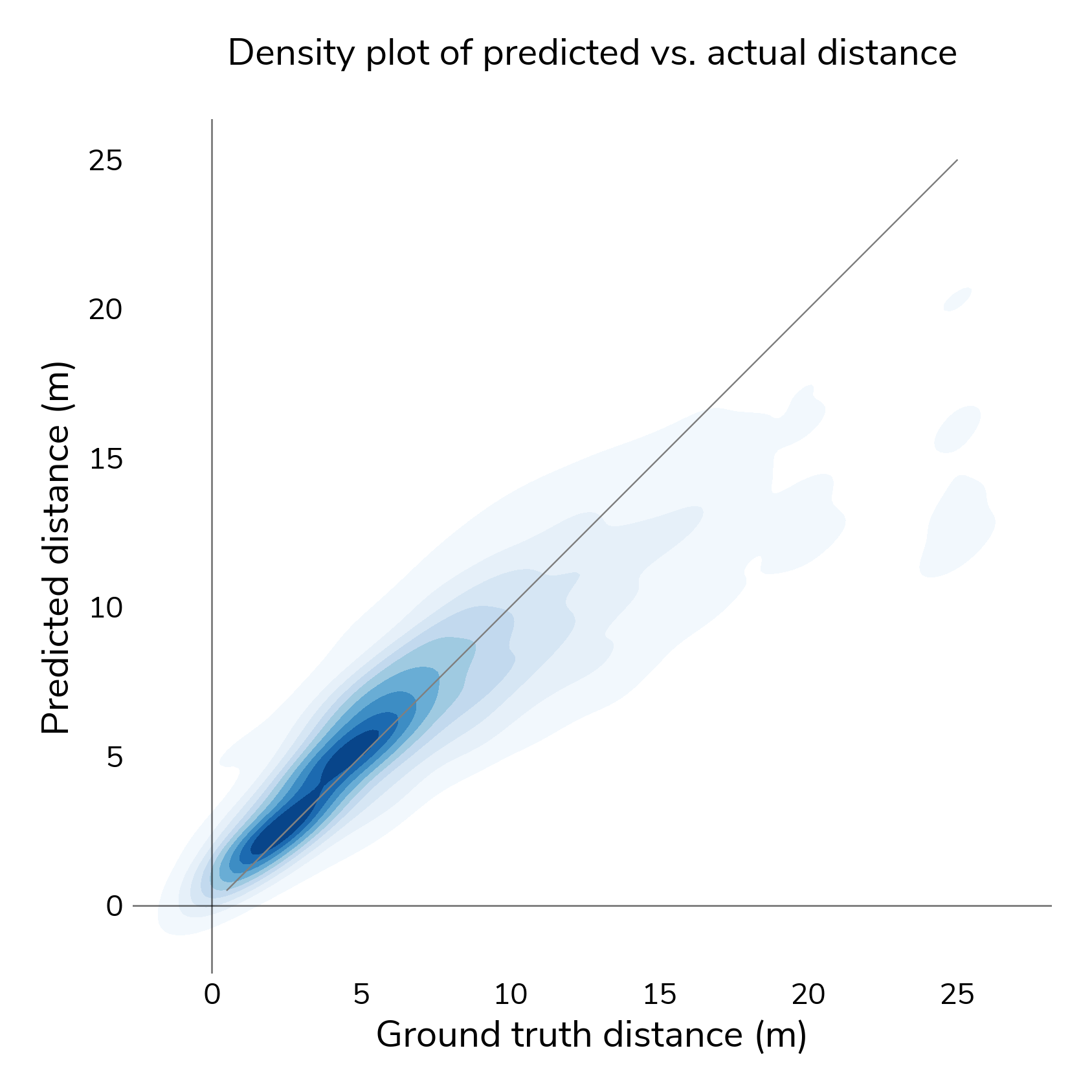

The depth estimation model has a mean absolute error (MAE) of 1.635 m. The model is more accurate when predicting depth for animals closer to the camera. The MAE for animals ≤10 m from the camera trap is 1.06 m, while at further distances, the model underestimates distance. However, accuracy at closer distances is more important for distance sampling methods Buckland et al., 2001.

Haucke et al. (2022) applied machine learning to monocular depth using reference videos and reported a mean absolute error (MAE) of 1.85 m. The relatively similar performance (albeit on different datasets) suggests that accurate machine learning predictions are possible without reference videos.

Figure 13:Density plot of predicted vs. actual distance for the depth estimation model

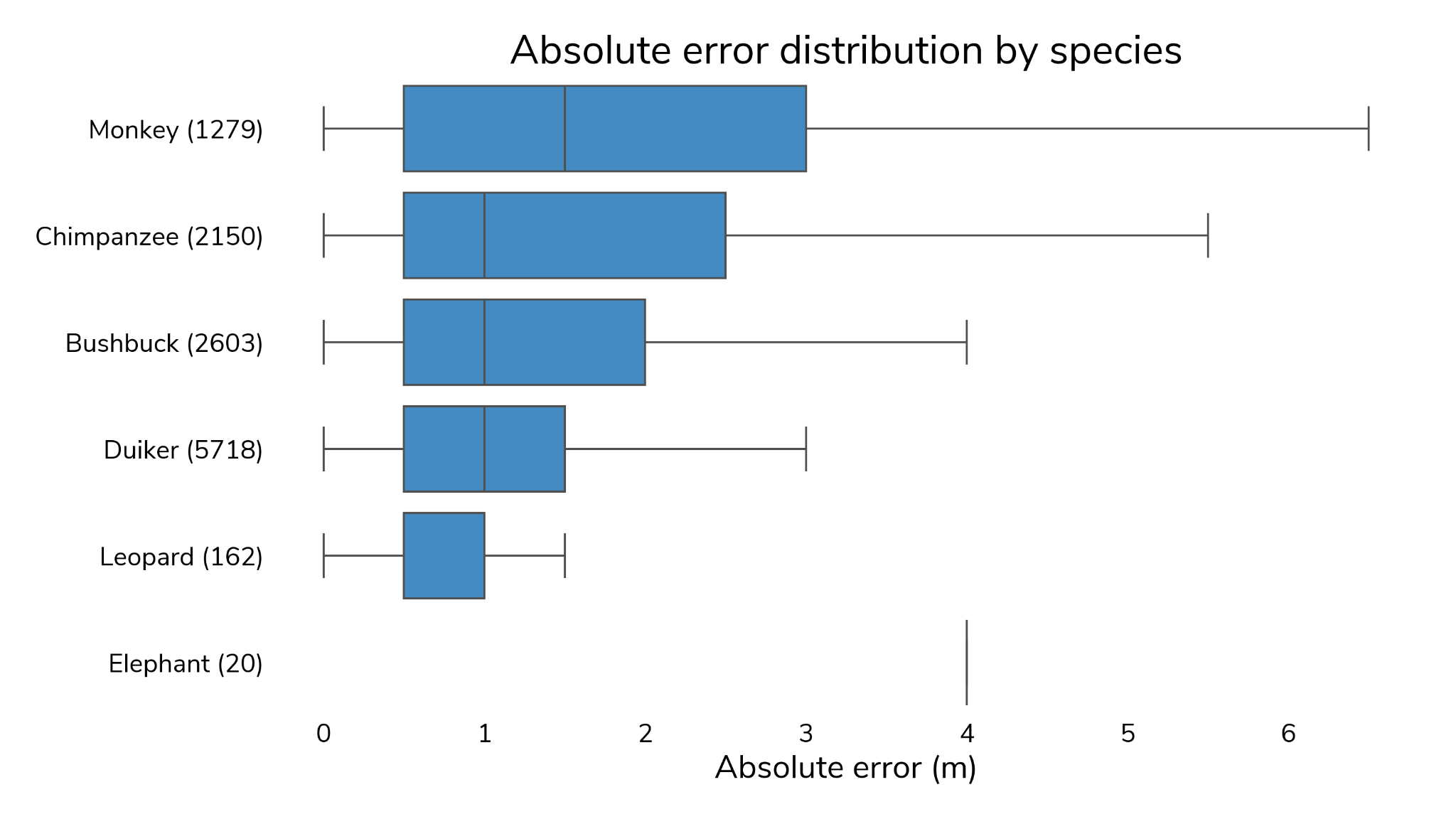

The median absolute error was relatively similar across species, though the distribution of errors differs a bit. Figure 14 show the interquartile range (shaded portion) of absolute errors by species. Outliers extending beyond 1.5 times the interquartile range are not plotted.

Figure 14:Distribution of test set absolute error by species.

7Zamba Cloud¶

As a command-line program and Python library distributed as a package, Zamba is capable and easily deployable. However, there are still two major limitations. First, not all researchers have such hardware available with graphical processing units (GPUs) to run deep learning models in a practical way. Without this specialized hardware running Zamba’s models on large datasets of videos or images is inefficient. Secondly, many wildlife conservationists are not programmers and may have little experience with command-line programs or scripting in Python, and it can be a barrier to create the environment and install the dependencies to run these tools.

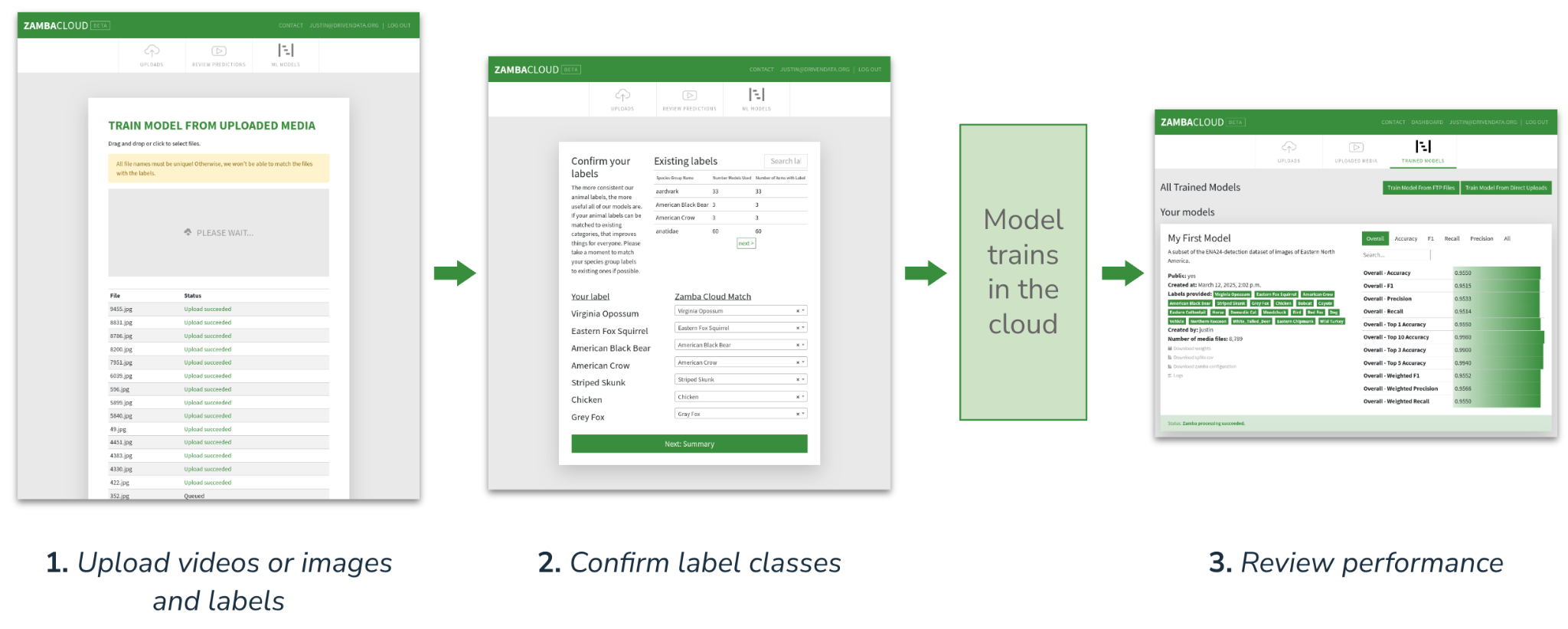

In order to make Zamba easy to use and accessible to any camera trap researcher, a point-and-click graphical-user interface program was developed. Zamba Cloud is a web application with no-code workflows to use Zamba’s capabilities. Zamba Cloud currently has workflows that support the species classification for videos and species classification for images tasks. For both tasks, users can fine-tune from any of Zamba’s pretrained models, and they can perform inference on unlabeled videos/images using a pretrained model, one of their fine-tuned models, or a fine-tuned model that another user has chosen to make publicly available.

All of the workflows start with uploading videos or images using a drag-and-drop interface. Alternatively, uploads via an FTP server are also supported. One key tradeoff of implementing a web application, as opposed to a desktop application, is that users are required to have internet access with sufficient bandwidth. To mitigate the bandwidth requirements, Zamba Cloud implements an optional upload process that performs client-side video resizing. This option uses ffmeg.wasm ffmpeg.wasm developers, 2019, a WebAssembly port of FFmpeg FFmpeg developers, 2000 to reduce the resolution and framerate of submitted videos to fixed sizes. If fine-tuning, users additionally upload label data and confirm whether they match to existing label classes or are new classes.

Figure 15:Screenshots showing the custom model fine-tuning workflow in Zamba Cloud.

Zamba Cloud runs all machine learning workloads on managed cloud infrastructure with GPUs. This means users can easily upload their data and use Zamba without needing specialized hardware or to install complex software.

For the inference workflow, Zamba Cloud has a review interface that allows users to easily visually inspect each image or video alongside predicted species classifications with confidence scores. For images, the bounding boxes from object detection are also shown. See Figure 16 for an example screenshot.

Figure 16:Screenshot of the prediction review interface in Zamba Cloud.

Predictions from the inference workflow are exportable in comma-separated values (CSV) format. CSV is chosen as a simple, open format that is portable and supported by common spreadsheet software.

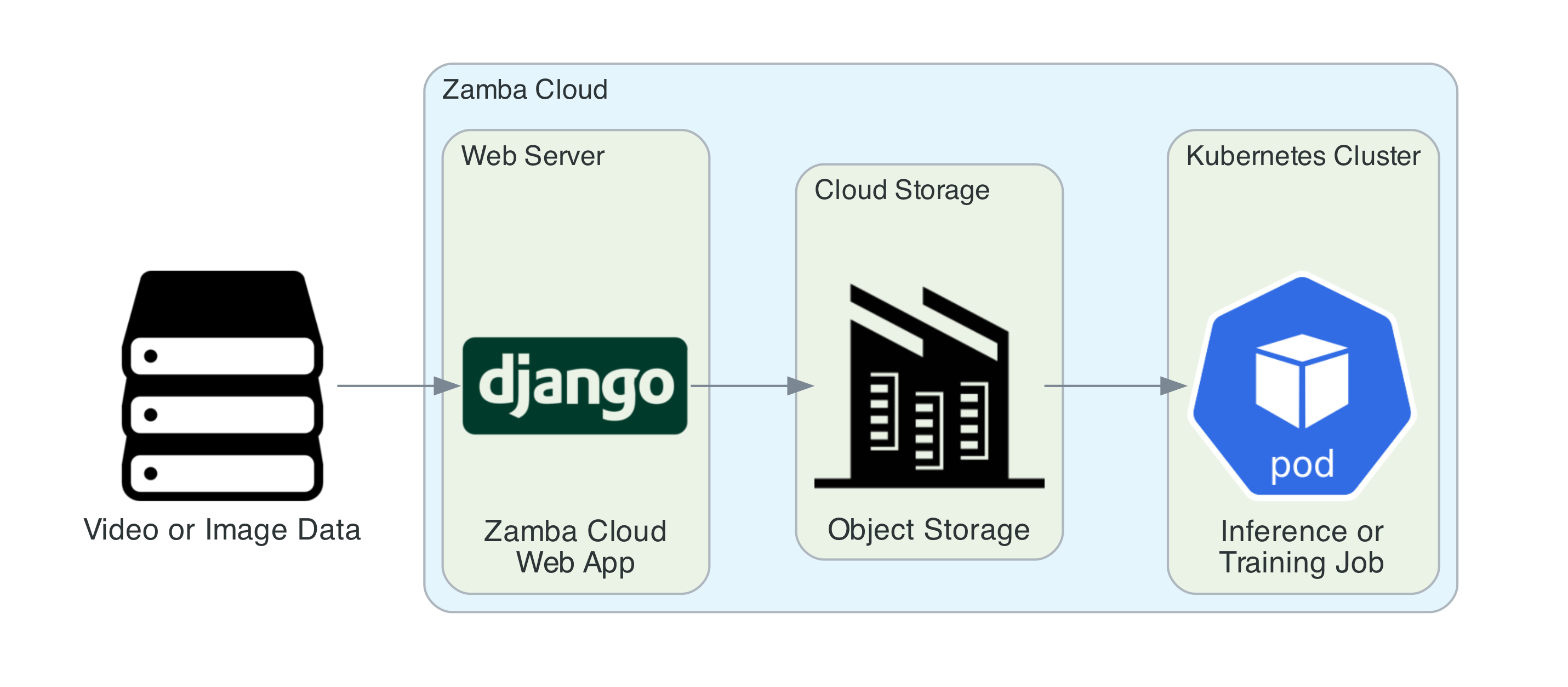

Zamba Cloud’s server is implemented in Python using Django Django developers, 2005. Machine learning workloads are containerized and submitted as batch jobs to a Kubernetes cluster.

Figure 17:Architecture diagram of Zamba Cloud.

8Discussion¶

Zamba implements workflows for inference on unlabeled videos or images using pretrained models as well as creating custom models by fine-tuning pretrained models with labeled data. Each of these tasks are available through the CLI or the Python library.

Custom model training represents Zamba’s flagship contribution and unique capability among camera trap analysis tools. Camera traps are used across hugely variable habitats, taxonomic rank, and camera positions. A single general pretrained model could not accommodate fish detected by underwater deployments, large mammals in the savannah, and insects captured in a hole in the ground. Zamba’s customization features dramatically expand applicability beyond users studying the species that existing pretrained models were trained on.

In addition, no-code workflows to use Zamba’s capabilities on Zamba Cloud means custom machine learning models are now accessible to non-programmers. To the best of our knowledge, Zamba Cloud is currently the only tool that supports fine-tuning custom video-native machine learning algorithms for camera traps without writing any code. To date, over 300 users from around the globe have used Zamba Cloud to process more than 1.1 million videos.

8.1Guidance on use¶

Zamba is designed to accelerate human workflows rather than replace human expertise, reducing the volume of videos that require manual review and removing procedural steps like identifying blank videos. Camera trap research often involves human coding (e.g., assessments of animal behavior) regardless of automated filtering or selection. At its current capability level, we recommend Zamba be used to inform research workflows rather than automate final outputs. The most common applications are:

Blank filtering: Zamba can be used to filter blank camera trap videos using probabilistic classifications, saving researchers significant time and storage costs. Researchers can adjust probability thresholds based on their priorities—setting conservative thresholds to avoid losing any animal videos, or more aggressive ones to maximize blank video removal.

Targeted species search: Zamba can be used to identify videos containing specific species of interest by sorting videos in descending order of probability for the target species. Targeted search saves researchers significant time and allows them to get more value out of camera trap data. Even with an imperfect model, researchers can focus on high confidence predictions overall or high confidence predictions within specific labels. Targeted search also enables collaboration between research groups, as one team’s bycatch can become another team’s primary data source.

Custom models: Custom models trained on user-provided data support use in new habitats or with different species. They can also be used to train site-specific models, which can yield more accurate predictions even if the species labels overlap with existing models, or improve classification of rare species. We recommend users first evaluate existing pretrained models before investing in custom training. When developing custom models, researchers should understand that the amount of data needed depends greatly on the specific data and use case, so we recommend an iterative approach. Label distribution in the training data will also affect model behavior: rare classes are harder for models to learn effectively, while balanced datasets may produce more false positives for genuinely rare species in deployment.

9Conclusion¶

Zamba is a powerful tool in supporting wildlife conservation. Initially developed to tackle the technically demanding task of processing camera-trap videos, it has since expanded to handle images as well. A key capability of Zamba is the ability to fine-tune models to better target specific habitats or expand to new subjects of interest, with support for species classification for both videos and images. The Zamba open source package supports programmatic use at the command line or as a Python library, while Zamba Cloud provides a no-code option for non-programmer users. The use of automated machine learning workflows for camera trap data can save countless hours of valuable time, speed up conservation interventions, and enable camera traps to be used to their fullest potential.

This project has been supported by funding from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, the Arcus Foundation, the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation, and the WILDLABS Awards 2024.

The authors express their gratitude to collaborators, advisors, and data providers at the following organizations: the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig, the Helversen’sche Stiftung, and Dan Morris.

The authors thank the following PanAf collaborators for supporting and collecting the PanAf video dataset: Abel Nzeheke, Alexander Tickle, Amelia Meier, Anne-Celine Granjon, Anthony Agbor, Dervla Dowd, Emmanuel Ayuk Ayimisin, Emmanuel Dilambaka, Emmanuelle Normand, Fiona Stewart, Geoffrey Muhanguzi, Giovanna Maretti, Henk Eshuis, Hilde Vanleeuwe, Jean Claude Dengui, John Hart, Joshua M. Linder, Jospehine Head, Juan Lapuente, Karsten Dierks, Katherine Corogenes, Kathryn J. Jeffery, Kevin Lee, Lucy Jayne Ormsby, Manasseh Eno-Nku, Martijn Ter Heegde, Mohamed Kambi, Nadege Wangue Njomen, Parag Kadam, Paul Telfer, Robinson Orume, Samuel Angedakin, Sergio Marrocoli, Sorrel Jones, Theophile Desarmeaux, Thurston Cleveland Hicks, Vera Leinert, Vianet Mihindou, Vincent Lapeyre, and Virginie Vergnes. The authors also thank the organizations and their members that have collaborated with the PanAf to collect this data: Budongo Conservation Field Station (Uganda), Fongoli Savanna Chimpanzee Project (Senegal), Gashaka Primate Project (Nigeria), Goualougo Triangle Ape Project, Greater Mahale Ecosystem Research and Conservation, Jane Goodall Institute Spain (Dindefelo, Senegal), Korup Rainforest Conservation Society (Cameroon), Lukuru Wildlife Research Foundation (DRC), Ngogo Chimpanzee Project (Uganda), Ozouga Chimpanzee Project and Loango Gorilla Project (Gabon), Station d’Etudes des Gorilles et Chimpanzees (Gabon), Tai Chimpanzee Project (Cote d’Ivoire), the Aspinall Foundation (Gabon), WCS (Conkouati-Douli NP, R-Congo), Wild Chimpanzee Foundation (Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea, Liberia), Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS Nigeria), WWF (Campo Ma’an NP, Cameroon), and WWF Congo Basin (DRC). The authors further thank the PanAf project and data managers: Paula Dieguez, Mizuki Murai, and Yasmin Moebius. The authors also thank the PanAf video data cleaners and Chimp&See community scientists and moderators who annotated the PanAf video data: Nuria Maldonado, Anja Landsmann, Laura K. Lynn, Zuzana Rockaiova, Heidi Pfund, Heike Wilken, Lucia Hacker, Libby Smith, Karen Harvey, Tonnie Cummings, Carol Elkins, Briana Harder, Kristeena Sigler, Jane Widness, Amelie Pettrich, Antonio Buzharevski, Eva Martinez Garcia, Ivana Kirchmair, Sebastian Schütte, Joana Pereira, Silke Atmaca, Sadie Tenpas, and all community scientists. The authors extend their deepest gratitude to the government organizations that have permitted data collection in their countries: Ministere de la Recherche Scientifique et de l’Innovation, Cameroon; Ministere des Forets et de la Faune, Cameroon; Ministere des Eaux et Forets, Cote d’Ivoire; Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique, Côte d’Ivoire; Agence Nationale des Parcs Nationaux, Gabon; Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Gabon; Ministere de l’Agriculture de l’Elevage et des Eaux et Forets, Guinea; Forestry Development Authority, Liberia; National Park Service, Nigeria; Ministere de l’Economie Forestiere, R-Congo; Ministere de la Recherche Scientifique et Technologique, R-Congo; Direction des Eaux, Forêts et Chasses, Senegal; Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology, Tanzania; Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute, Tanzania; Makerere University Biological Field Station Uganda; Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, Uganda; Uganda Wildlife Authority, Uganda; National Forestry Authority, Uganda. The authors also thank the generous funders of PanAf: Max Planck Society, Max Planck Society Innovation Fund, Heinz L. Krekeler Foundation, Arcus Foundation, the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation, Google AI for Social Good, and Facebook.

The authors thank the other contributors to the Zamba and Zamba Cloud codebases: Justin Chung Clark, Casey Fitzpatrick, Robert Gibboni, Tamara Glazer, Isaac Slavitt, Stan Triepels, and Katie Wetstone. The authors also thank Dmytro Poplavskiy, the winner of the Pri-Matrix Challenge, whose winning solution was the basis for the original Zamba V1 video species classification model; and Kirill Brodt, the second-place winner of the Deep Chimpact Challenge, whose solution is the basis for the depth estimation model. The authors thank Hannah Moshontz de la Rocha for review and edits to the manuscript. Finally, the authors thank the reviewers who provided constructive comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Copyright © 2025 Dorne et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creators.

Since this data was non-expert labeled, certain thresholds on how many user annotations were required to accept a label as well as thresholds related to percentages of user agreement were applied to go from raw annotations to a well-labeled dataset.

Since Zamba’s origins in 2017, computer vision techniques have evolved significantly. The original algorithm implemented in Zamba v1 used an ensemble of five models with architectures based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs)—ImageNet—ResNet50, ResNet152 He et al., 2015, InceptionV3 Szegedy et al., 2015, Xception Chollet, 2016, and Inception-ResNetV2 Szegedy et al., 2016. Base models trained on ImageNet were fine-tuned. Then, class probabilities for 32 frames per clip were aggregated into summary statistics and passed to a second-level XGBoost Chen & Guestrin, 2016 model, which generated the final species prediction. DrivenData, 2018 This model was replaced in 2021 with the release of Zamba v2 so is not discussed in more depth here.

This retraining update also addressed artifacts from the original competition. For example, the competition’s lack of site-aware splitting contributed to inflated performance metrics by allowing models to learn location-specific features from backgrounds. Additionally, labeling errors stemming from crowd-sourced annotations were corrected using a curated set of 125,000 expert-labeled videos, which significantly improved performance for certain species.

These output classes were selected based on the research needs of the data providers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

Other architectures evaluated during development in 2021 included image-based and video-based models such as ResNet He et al., 2016, R2Plus1D Tran et al., 2018, TimeSFormer Bertasius et al., 2021, X3D Feichtenhofer, 2020, and I3D Carreira & Zisserman, 2017.

The label classes for the

time_distributedandslowfastAfrican species models are: aardvark,antelope_duiker,badger,bat,bird,blank,cattle,cheetah,chimpanzee_bonobo,civet_genet,elephant,equid,forest_buffalo,fox,giraffe,gorilla,hare_rabbit,hippopotamus,hog,human,hyena,large_flightless_bird,leopard,lion,mongoose,monkey_prosimian,pangolin,porcupine,reptile,rodent,small_cat,wild_dog_jackalThe label classes for the

europeanmodel are:bird,blank,domestic_cat,european_badger,european_beaver,european_hare,european_roe_deer,north_american_raccoon,red_fox,weasel, andwild_boarThis parameter was found empirically via crowd-sourced experimentation by participants in the Pri-matrix Factorization Challenge to be sufficient for accurately classifying videos while balancing the overall computational requirements of the pipeline. Users may choose to tune this parameter for their particular dataset and use case. See the “Configuration and customization” section.

Top-1 accuracy is defined as the percentage of videos where the class with the highest predicted probability is actually present.

Top-3 accuracy is the percentage where the true class appears among the top three predicted classes.

This means all images from a given transect (camera location) are assigned entirely to one split. This methodology is the same as what we used for splitting the video data.

As discussed for video species classification, it is difficult to report meaningful direct comparisons to other tools or study results. There are not well-established standard benchmarking procedures and datasets, and the high degree of variance in attributes across camera trap deployments means that performance is highly sensitive to similarity to the training data, and that metrics reported on one dataset do not necessarily translate well to others.

The second-place submission was chosen for modeling framework compatibility reasons. While the full competition-winning approach was an ensemble, the performance of the best single model was almost identical to the ensemble (MAE of 1.635m for the single model compared to 1.625m for the ensemble) so only one model was integrated into Zamba. This supports lower computing costs and faster inference speeds without sacrificing performance.

Training and fine-tuning is not supported as of version v2.6.1 (May 2025).

Although the model was trained on single-individual videos, it produces an output for each detected animal in a frame. However, for frames with multiple individuals, the distance for all animals will be the same. If there is no animal in the frame, the distance will be null.

These hyperparameters were part of the second-place winning solution of the Deep Chimpact Challenge and found empirically.

- CNN

- Convolutional neural network

- CSV

- Comma-separated values

- ECDF

- Empirical cumulative distribution function

- FTP

- File transfer protocol

- ML

- Machine learning

- MPI-EVA

- Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

- WCF

- Wild Chimpanzee Foundation

- Burton, A. C., Neilson, E., Moreira, D., Ladle, A., Steenweg, R., Fisher, J. T., Bayne, E., & Boutin, S. (2015). REVIEW: Wildlife camera trapping: a review and recommendations for linking surveys to ecological processes. Journal of Applied Ecology, 52(3), 675–685. 10.1111/1365-2664.12432

- Arandjelovic, M., Stephens, C. R., Dieguez, P., Maldonado, N., Bocksberger, G., Després‐Einspenner, M., Debetencourt, B., Estienne, V., Kalan, A. K., McCarthy, M. S., Granjon, A., Städele, V., Harder, B., Hacker, L., Landsmann, A., Lynn, L. K., Pfund, H., Ročkaiová, Z., Sigler, K., … Kühl, H. S. (2024). Highly precise community science annotations of video camera‐trapped fauna in challenging environments. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation, 10(6), 702–724. 10.1002/rse2.402

- Vélez, J., McShea, W., Shamon, H., Castiblanco‐Camacho, P. J., Tabak, M. A., Chalmers, C., Fergus, P., & Fieberg, J. (2022). An evaluation of platforms for processing camera‐trap data using artificial intelligence. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 14(2), 459–477. 10.1111/2041-210x.14044

- DrivenData, Bull, P., Dorne, E., Gibboni, R., Qi, J., & Wetstone, K. (2022). Zamba. Zenodo. 10.5281/ZENODO.15116959

- Rovero, F., & Kays, R. (2021). Camera trapping for conservation. In Conservation Technology (pp. 79–104). Oxford University PressOxford. 10.1093/oso/9780198850243.003.0005

- Tobler, M. W., Zúñiga Hartley, A., Carrillo‐Percastegui, S. E., & Powell, G. V. N. (2015). Spatiotemporal hierarchical modelling of species richness and occupancy using camera trap data. Journal of Applied Ecology, 52(2), 413–421. 10.1111/1365-2664.12399

- Sollmann, R., Mohamed, A., Samejima, H., & Wilting, A. (2013). Risky business or simple solution – Relative abundance indices from camera-trapping. Biological Conservation, 159, 405–412. 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.12.025

- Howe, E. J., Buckland, S. T., Després‐Einspenner, M., & Kühl, H. S. (2017). Distance sampling with camera traps. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 8(11), 1558–1565. 10.1111/2041-210x.12790

- O’Brien, T. G., Ahumada, J., Akampurila, E., Beaudrot, L., Boekee, K., Brncic, T., Hickey, J., Jansen, P. A., Kayijamahe, C., Moore, J., Mugerwa, B., Mulindahabi, F., Ndoundou‐Hockemba, M., Niyigaba, P., Nyiratuza, M., Opepa, C. K., Rovero, F., Uzabaho, E., & Strindberg, S. (2019). Camera trapping reveals trends in forest duiker populations in African National Parks. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation, 6(2), 168–180. 10.1002/rse2.132

- Caravaggi, A., Banks, P. B., Burton, A. C., Finlay, C. M. V., Haswell, P. M., Hayward, M. W., Rowcliffe, M. J., & Wood, M. D. (2017). A review of camera trapping for conservation behaviour research. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation, 3(3), 109–122. 10.1002/rse2.48

- Bessone, M., Kühl, H. S., Hohmann, G., Herbinger, I., N’Goran, K. P., Asanzi, P., Da Costa, P. B., Dérozier, V., Fotsing, E. D. B., Beka, B. I., Iyomi, M. D., Iyatshi, I. B., Kafando, P., Kambere, M. A., Moundzoho, D. B., Wanzalire, M. L. K., & Fruth, B. (2020). Drawn out of the shadows: Surveying secretive forest species with camera trap distance sampling. Journal of Applied Ecology, 57(5), 963–974. 10.1111/1365-2664.13602

- Green, S. E., Rees, J. P., Stephens, P. A., Hill, R. A., & Giordano, A. J. (2020). Innovations in Camera Trapping Technology and Approaches: The Integration of Citizen Science and Artificial Intelligence. Animals, 10(1), 132. 10.3390/ani10010132

- Beery, S., Morris, D., & Yang, S. (2019). Efficient Pipeline for Camera Trap Image Review. arXiv. 10.48550/ARXIV.1907.06772

- Haucke, T., Kühl, H. S., Hoyer, J., & Steinhage, V. (2022). Overcoming the distance estimation bottleneck in estimating animal abundance with camera traps. Ecological Informatics, 68, 101536. 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101536

- Ahumada, J. A., Fegraus, E., Birch, T., Flores, N., Kays, R., O’Brien, T. G., Palmer, J., Schuttler, S., Zhao, J. Y., Jetz, W., Kinnaird, M., Kulkarni, S., Lyet, A., Thau, D., Duong, M., Oliver, R., & Dancer, A. (2019). Wildlife Insights: A Platform to Maximize the Potential of Camera Trap and Other Passive Sensor Wildlife Data for the Planet. Environmental Conservation, 47(1), 1–6. 10.1017/s0376892919000298