Jupyter Book 2 and the MyST Document Stack

Abstract¶

Jupyter Book allows researchers and educators to create books, articles, and collections of connected documents that are reusable, reproducible, and interactive. Over the past three years, Jupyter Book has been entirely rebuilt on top of the MyST Document Engine and its ecosystem of tools and standards. This new foundation introduces a scalable way to publish modern scientific content that enables interactive code and computation, structured metadata, and content reuse across contexts. It allows for a more fluid workflow between computational discovery and communication, treating computation as first-class in both authoring and reading. Jupyter Book 2 (JB2) is now a Jupyter sub-project, and already powers several open scientific resources including The Turing Way, QuantEcon, Project Pythia, and the QIIME 2 Framework (Q2F) documentation ecosystem. This paper introduces the principles, architecture, and capabilities of JB2, shares real-world adoption stories, and explores how these tools are shaping the future of open computational publishing.

1Introduction¶

Jupyter Book Executable Books Community, 2020 has become a widely used tool in computational science and open publishing, powering over 18,000 publicly available books[1], lectures, tutorials, and knowledge repositories. It enables clear communication of both exploratory computation and narrative text, making it possible to document, share, and publish computational workflows in accessible formats.

With Jupyter Book 2 (JB2), the project has undergone a major transformation. Jupyter Book 2 is now a distribution of the MyST (Markedly Structured Text) Document Engine[2]; every book built with Jupyter Book 2 is also a MyST project, and building a book with Jupyter Book 2 means building a MyST project. Jupyter Book 2 heavily utilizes components from the MyST ecosystem—a collection of open source tools and standards for authoring open computational narratives. This is similar to the relationship between Jupyter Book 1 and Sphinx.

The goal of this overhaul is to make structured scientific content more interoperable, composable, extensible, and machine-readable. This enables researchers to publish high-quality, interactive content with support for standards-based reuse, full-text APIs, executable notebooks, and output formats like Websites, Typst, PDF, LaTeX, Microsoft Word, JATS XML (Journal Article Tag Suite, used in scientific publishing), and more. It is a major step forward towards Jupyter’s vision of thinking and storytelling with code and data Granger & Perez, 2021Thomas et al., 2016.

In this article, we: (a) document the guiding principles and design thinking behind this major release; (b) present the high-level architecture behind Jupyter Book and the MyST ecosystem; (c) compare our tools to others in the scientific publishing ecosystem; and (d) highlight case studies of notable projects.

2The challenge: Bridging Exploration and Publication¶

The mission of Jupyter Book and MyST is to build composable tools and standards for communicating technical and computational narratives. This must encompass the full lifecycle of discovery and communication from informal lab notes and collaborative tutorials to formal research articles and textbooks. Our goal is to support authors, educators, and researchers as they share work within local communities and publish across the global scientific commons.

We are focused on two overlapping but distinct communities:

- Data-driven communicators¶

- Researchers, analysts, and educators who need to share working, reproducible content with collaborators, students, or the public. These users rely on Jupyter, Python, and other computational tools in their daily workflows, but often lack well-integrated systems to communicate what they’ve done or how to reproduce it.

- Scholarly Authors and Publishers¶

- Scientists and academics preparing content for peer review, journals, repositories, or formal documentation, and organizations that serve these users. They need structured metadata, citation systems, and outputs compatible with academic and institutional publishing pipelines.

Both of these groups are underserved by the current ecosystem of open source technology. Today’s scientific workflows rely on computational tools like Jupyter Notebooks, yet the systems used to communicate and publish these workflows are fragmented and poorly integrated. For example, researchers often do their work in an interactive computing environment designed for exploration, and must then adopt an entirely new toolchain for publishing their work. As a result, researchers must spend time adapting to new workflows, duplicating and reformatting their content just for the sake of publishing. Because output-specific pipelines, such as PDF generation, are fairly constrained, published work is often stripped of its computational context, leaving no mechanism to access software environments and reproduce results.

Over the years, there have been many attempts at improving this workflow with new technologies and standards (several are discussed below), but none have provided the combination of flexibility, standards-based implementation, and community governance needed to cover the entire lifecycle from idea to communication described above. Jupyter Book 2 and the MyST Ecosystem is an attempt to bridge this gap.

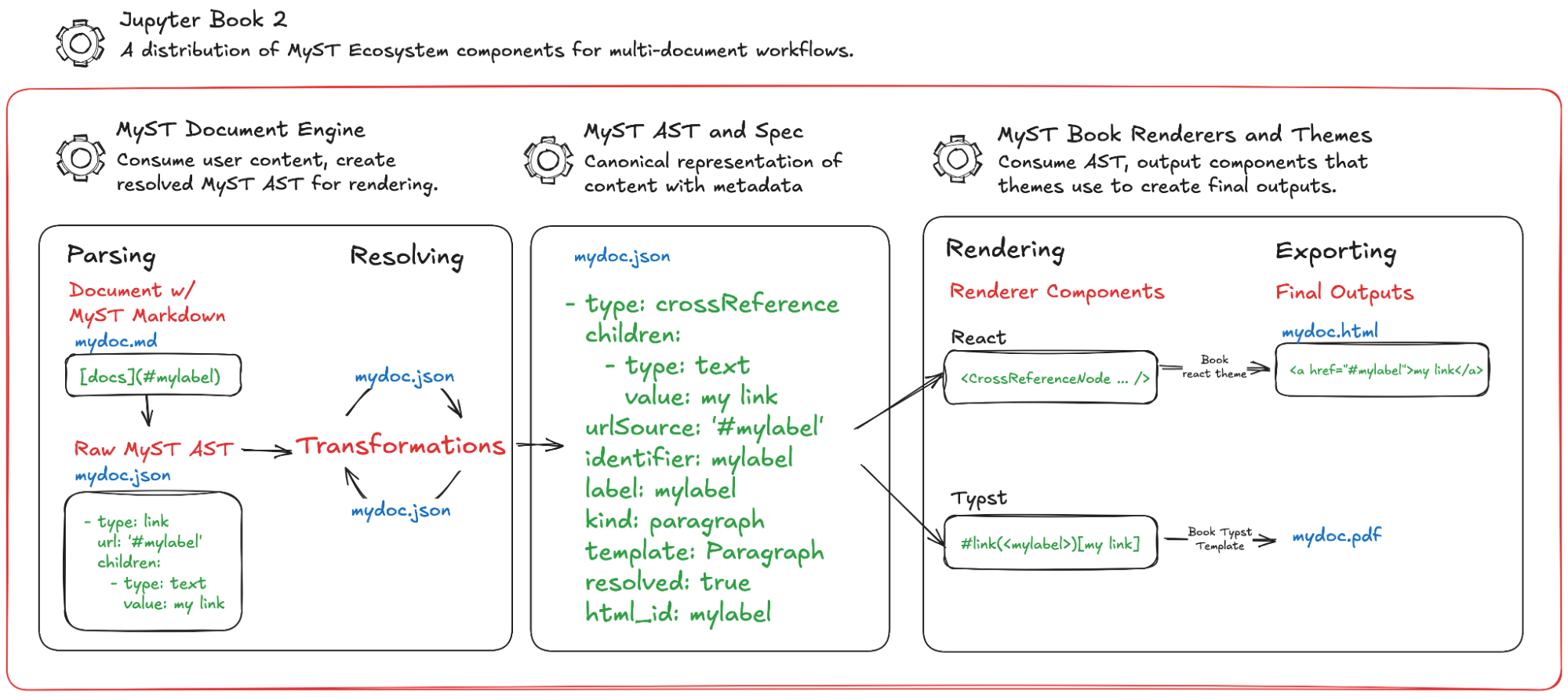

2.1Overview of Jupyter Book 2’s architecture¶

This section describes the architectural structure and components that drive the Jupyter Book 2 stack and the MyST ecosystem. At the heart of JB2 and the MyST ecosystem are four pieces:

The MyST Document Engine (https://mystmd.org), a publication system for authoring computational narratives.

The MyST Specification (https://

mystmd .org /spec), a structured and semantically-meaningful way of representing computational content in an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). MyST Renderers and Themes (https://

mystmd .org /guide /overview #overview -themes), transform MyST ASTs into end-user outputs (websites, PDFs, etc.). MyST Markdown A lightweight extension of CommonMark Markdown[3] and GiHub Flavored Markdown (GFM[4]) which adds roles and directives (described below).

JB2 combines these and other MyST components into an end-user application meant for community knowledge bases and books. This new architecture is designed to enable dynamic rendering, multi-format output, and composable content workflows—backed by a structured document model that makes metadata, structure, and computation portable and machine-readable.

Figure 1:High-level overview of Jupyter Book 2 components. JB2 combines several components in the MyST ecosystem, configured for multi-document workflows such as community knowledge bases, websites, and books. The MyST Document Engine parses MyST Markdown (and other flavors of text-based content) into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) that follows the MyST Document Specification. It resolves and transforms this AST to enrich it with extra document metadata (such as resolving DOIs). The engine then renders this AST to React components that are bundled with the Book Theme, which makes up the end-user application most-often used with JB2.

2.2The MyST Engine: A simple, powerful, and extensible document engine¶

The MyST Document Engine allows users to parse documents into a structured format, execute computational content, transform them to include metadata and resolve references, and output a resolved MyST Abstract Syntax Tree (AST, described in more detail below). It is run via the command-line and is written in TypeScript. It parses many types of inputs—Markdown files, Jupyter Notebooks, LaTeX documents, external MyST projects, configuration files, etc—and ensures that all of their content is embedded in this output AST.

2.3The MyST Specification: A Structured Computational Document Format¶

The MyST Specification defines all of the types of content and metadata that make up a computational narrative. It is meant to be a cross-platform standard that can be used by various applications and parsers in order to facilitate sharing and re-use of content.

The MyST Document Engine outputs a MyST Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) that follows the MyST Specification. The AST is a machine-readable representation of each document’s content and structure. It preserves not only the narrative content, but also computational blocks, computational outputs from Jupyter Notebooks, citations, figures, and metadata such as author affiliations and license information. These are all built into a structured, versioned AST. It is a Canonical Document Representation that can be parsed and rendered into user-facing outputs by renderers and themes.

MyST Markdown is a flavor of Markdown written for the MyST Specification that gives authors quick access to these and other extension points. MyST Markdown supports syntax for all of the content types supported in the MyST Specification. It is used both in Jupyter Book 2 and the MyST Engine, as well as in the Sphinx ecosystem via the myst-parser extension.

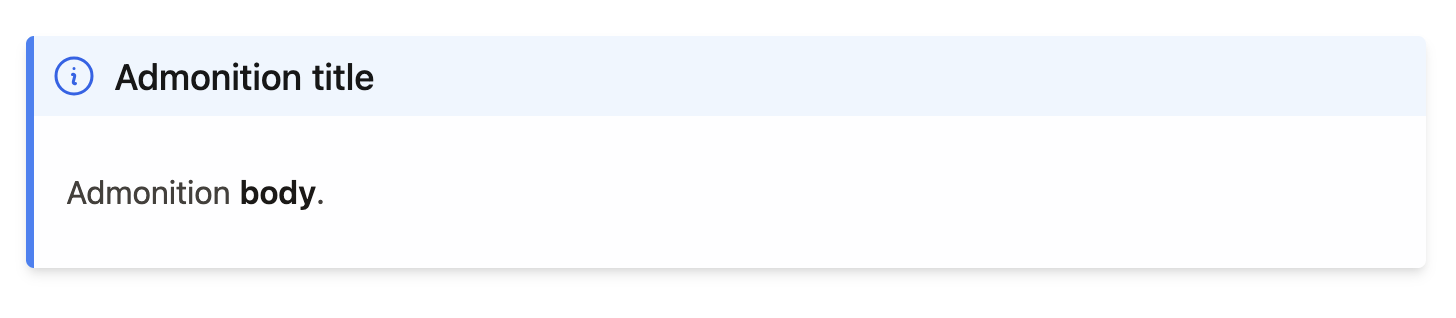

As an example, see the example note directive written in MyST Markdown below (for more information on directives, see the sections below).

:::{note} Admonition title

Admonition **body**.

:::The MyST Document Engine parses this Markdown content into an AST that follows the MyST Specification. It looks like this:

- type: admonition

kind: note

children:

- type: admonitionTitle

children:

- type: text

value: Admonition title

- type: paragraph

children:

- type: text

value: 'Admonition '

- type: strong

children:

- type: text

value: body

- type: text

value: ...Renderers then convert this AST into various output formats.

2.4MyST Renderers and Themes: Tools to convert MyST AST into user-facing products¶

MyST Renderers and Themes are tools for converting documents that follow the MyST Specification into user-facing outputs, such as websites and PDFs.

Renderers are essentially a collection of rules for converting each type of content (called a “node” in a MyST AST) into an output.

For example, the MyST AST for the Note admonition above would be rendered into a React component, and exported to HTML via the static HTML export command jupyter book build --html like so:

<-- React component used by the Book or Article theme -->

<Admonition title="Note" kind="{AdmonitionKind.note}" color="blue">

This is an admonition!

</Admonition>

<-- React component converted to this HTML after static HTML export -->

<aside className="myst-admonition myst-admonition-note">

<div className="myst-admonition-header">

<InformationCircleIcon className="myst-admonition-header-icon" />

<div className="myst-admonition-header-text">Note</div>

</div>

<div className="myst-admonition-body">This is an admonition!</div>

</aside>The Book React Theme defines the basic structure and styles of a Jupyter Book 2, and is the default result that most users get when they render their books as websites. The React component above is styled by the Book Theme into this final product:

Figure 2:Example admonition component. The final product of a MyST Admonition rendered by the Book Theme. Arguments and keywords in the {note} directive influence the look and feel of this final product.

Importantly, MyST Renderers can be written for any kind of output.

For example, there is a Typst renderer and a LaTeX renderer, which can themselves be customized with themes to generate different types of outputs.

Jupyter Book 2 ships with a default Book Theme for each type of renderer, but we imagine our ecosystem of users extending this to include, for example, LaTeX templates for a variety of Journals.

The myst-templates GitHub organization (github

2.5Jupyter Book 2: A distribution of MyST components¶

Finally, Jupyter Book 2 is a lightweight distribution and configuration layer on top of these and other components of the MyST ecosystem. It is meant to provide an opinionated experience of MyST–for example, by turning on certain features by default, and by providing an out-of-the-box theme meant for multi-document websites. At its core, Jupyter Book 2 functionality is leveraging components in the MyST ecosystem.

This is a pattern that we wish to encourage and grow in the MyST ecosystem. Tools like the MyST Document Engine aim to be unopinionated, modular, configurable, and extendable. They’re primarily meant for use by power users and developers who are interested in configuring MyST tools for their own needs/community, or building MyST tools into separate applications. Jupyter Book 2 is meant for end-users like researchers and educators who want an opinionated system for communicating computational narratives that “just works”.

We envision that a broader ecosystem of high-level tools and services—similar to Jupyter Book 2 itself—may be built on top of the MyST Document Engine, Specification, Renderers, and other components. With that in mind, we now turn to the design principles that drove the architecture of the MyST ecosystem, and the value that they bring to the open science community.

3Design Principles¶

Jupyter Book 2 is designed to meet the practical needs of researchers, educators, and publishers who communicate with—and about—data. It also supports developers in the open science ecosystem who build applications on shared standards and tools. We have grounded the design and development of the JB2 stack with the following principles.

- Simple to use, easy to extend¶

- Users should be able to run common workflows with minimal complexity, dependencies, setup, and configuration. Power-users should be able to extend this functionality with minimal effort.

- Use standardized, machine readable formats¶

- There should be a canonical, machine-readable representation of all content, allowing it to be re-used and rendered into multiple outputs without losing structure, metadata, or intent.

- Content should be modular and composable¶

- Canonical content should be made up of small, reusable components to enable reuse, cross-referencing, and re-mixing into diverse outputs.

- Computation should be first-class¶

- Code, data, and outputs are treated as integral components of the research narrative, for example, integrated and reproducible ways to calculate figures, show inline values, and cache computations.

- Open science infrastructure should be governed by an open community¶

- Jupyter Book and MyST should be stakeholder-led, with a diverse community of organizations and people from the open science community that guide its development.

Below, we describe each in more detail, how it is implemented in the MyST ecosystem, and the value that it brings to communicating open science with computational narratives.

3.1Simple and quick to use, easy to extend¶

First and foremost, it should be simple and straightforward for authors to create and publish computational narratives with Jupyter Book 2, requiring little configuration and customization. If the out-of-the-box functionality of Jupyter Book 2 doesn’t fit an author’s needs, there should also be simple mechanisms to extend Jupyter Book’s functionality. The MyST ecosystem should be composed of independent pieces that can work together as a whole, with natural ways to extend for new functionality.

3.1.1MyST’s plugin ecosystem¶

The MyST Documentation engine has several key extension points that allow users to add new functionality in a controlled way[5]. Below are a few key extension points:

Roles and directives are mechanisms for adding new types of in-line and block-level content (respectively), allowing developers to define content abstractions (similar to functions in a programming language) for use by authors.

Users may define their own roles and directives using JavaScript, Python, or any other language that reads and writes from stdout.

Building a new role or directive involves taking MyST AST as input, applying transformations, and returning AST.

Transforms are a mechanism for transforming the content of one or more MyST ASTs.

It is used to enrich content as part of the build process.

For example, by collecting {figure} nodes throughout the page and aggregating them into a single gallery.

Renderers are a way to export MyST AST into arbitrary types of outputs. They’re useful for converting the “Canonical document” into many different formats or styles without changing the original content. They are explained in sections below.

3.2Content should be canonical and machine readable¶

The MyST ecosystem emphasizes a “content-first” model, where authoring is separated from output format. This reduces the friction and wasted time associated with re-packaging source content in order to build a slightly different output.

3.2.1The MyST AST is semantically structured¶

The MyST Document Engine produces a machine-readable abstract syntax tree for every page. This well-structured build artifact is a canonical document that describes the underlying structure, content, and metadata of the document. This internal representation captures not just the text of a document, but also its semantic components: citations, headings, roles, directives, code blocks, figures, equations, and embedded metadata like Open Researcher and Contributor IDs (ORCIDs), Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs), or author affiliations via the Research Organization Registry (ROR). A canonical version also allows content to be rendered into multiple outputs—without losing structure, metadata, or intent.

By embedding all of the relevant metadata in a MyST Document, it is possible to gain a more rich understanding of the intent, context, and learning contained within a document. It is also possible to (re)use subsets of this information for various end purposes (for example, to re-render a figure, or to provide metadata for a scientific discovery engine). We give specific effort to support the open-science ecosystem, especially around structured, scholarly metadata that help discoverability (e.g., DOIs, ORCIDs, RORs).

3.2.2Many renderers operate on the same AST¶

The AST serves as the canonical version for rendering content into multiple target formats: web-native HTML, JATS XML, PDF via Typst or LaTeX, Microsoft Word, and more. Exporting to a target format is done with a renderer that consumes the AST and applies format-specific styling, layout, and transformations. Our attention is primarily focused on the React-renderers, Typst PDF templates (a new PDF renderer that is significantly faster than LaTeX), and JATS XML used in scholarly publishing. For example, the SciPy Proceedings for 2024 and 2025 both use the React renderers, the Typst renderer for PDF creation, and JATS XML for all articles Cockett et al., 2024.

By treating that document AST as a first-class build output, authors can write their content once, and publish in multiple places without manually adapting their content for each target format.

For example, a MyST Document can be built once, and the resulting AST can be rendered into an HTML website as well as multiple LaTeX documents for submission to various journals.

Paired with the machine readability of the AST (the .json file served with websites), it is possible to render multiple “views” of the same underlying content without creating confusion for where the source of truth lies.

Additionally, having a standard and metadata-rich AST structure allows many different workflows to be served from the same document engine. For example, while this article focuses on the multi-document workflow of Jupyter Book 2, the MyST Document Engine has also been used as part of scholarly article publishing pipelines, which are composed of independent articles that benefit from the same ability to cross-reference one another. For example the Proceedings of SciPy have been published with the MyST Document Engine for the last two years, the Notebooks Now! project Fernando Pérez, 2025 incorporated MyST-based publishing into the American Geophysical Union proceedings for the last several years, the NeuroLibre project has built a pre-print server using the MyST engine, and Curvenote builds a publishing platform using MyST components Cockett et al., 2024. By enabling a variety of publication output types with the same underlying document engine, the MyST ecosystem can reduce duplicated technology and streamline the workflow from data science and documentation to publishing.

Figure 3:Rendering a single AST into many output types. In this workflow, a single collection of source files (a) are built into a MyST AST (b) that serves as the canonical representation of the document. One or more renderers operate on that AST and convert them into outputs (c) such as HTML, PDF, Microsoft Word, etc. (Figure adapted from Cockett et al. (2024), showing content from Cockett et al. (2016); CC-BY-SA-4.0).

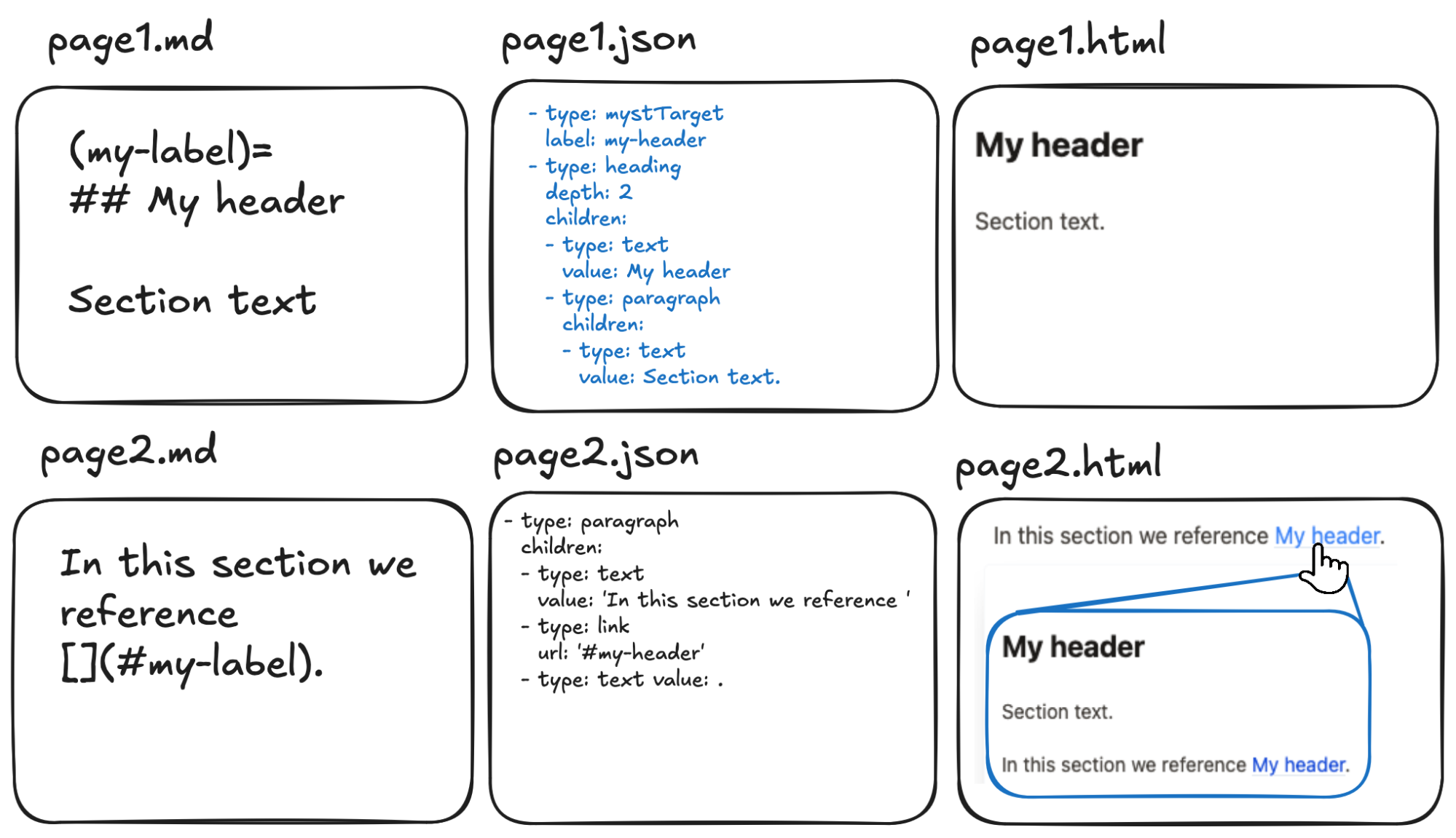

3.3Content should be modular and composable¶

The MyST ecosystem is designed for composition. Documents are structured into small, addressable components: sections, figures, equations, terms, figures, outputs—that can be reused across books, projects, and publications. This modularity supports new patterns of collaboration and publication: a figure generated in a course textbook can be cited and embedded in a tutorial or a journal article without duplication or loss of provenance. A community policy or database can be re-used throughout many pages in its documentation without duplicating information and creating multiple sources of truth. Additionally, configuration for a collection of projects can be shared and reused.

3.3.1The MyST AST modularizes content for easy parsing and re-mixing¶

Each page or resource in a Jupyter Book project is assigned a unique slug (a human-readable URL) and corresponding AST.

These can be referenced across projects, embedded in-line with other page content, or previewed when users hover over links.

This is based on both the MyST Specification and a machine-readable cross-reference manifest myst.xref.json[6].

Similar to intersphinx references, a feature for cross-project linking in the Sphinx documentation generator, the myst.xref.json gives stable links to any aspect of the content.

This makes it easy to programmatically learn the structure of a Jupyter Book, referenceable labels, and the location of the canonical content for each document.

An author can then reference labels in a different Jupyter Book or MyST project with an xref link.

For example, the MyST Markdown below demonstrates referencing an external project called other-project (assuming that the URL of the other project is defined in your MyST configuration).

[Link text](xref:other-project#label-name)This also allows authors to reference any other Jupyter Book or MyST project , and use xref: links to link or embed the content.

These links are either generated at build- or render-time, and allow for dynamic linking between projects with a simple user interface.

Paired with structured JSON APIs for document content (described below), it also allows machines to efficiently access data in a Jupyter Book (for example, to enable hover-previews or to identify source files for HTML pages for use by Large Language Models)[7].

3.3.2API-Accessible and Federated by Design¶

The Canonical AST of each document is designed to be re-used by others.

It is packaged as a machine-readable .json file to encourage programmatic re-use.

It is also bundled with web outputs to encourage external services or readers to access and utilize the AST via a machine-readable metadata endpoint (/pagename.json).

Machine readable content accessible via an API is one of the most transformative aspects of the JB2 architecture.

By making each canonical document accessible via a .json API endpoint that exposes its AST and metadata, content can be programmatically indexed, referenced, embedded, transcluded, or transformed without needing to scrape or recompile the site.

Readers and developers can query structure, citations, and content across books, enabling new tools like federated search, content previews, and live citation graphs.

It also enhances the reading experience by enabling full-text search, granular cross-referencing, and live content embedding across projects.

Moreover, by aligning with community standards (e.g., JATS, DOIs, ORCID, ROR), the system supports today’s scholarly publishing workflows, remains grounded in lightweight, Markdown-based authoring, and opens up possibilities for more composable workflows in the future for scientific authoring Cockett et al., 2025. This approach lays the groundwork for a federated publishing network where content from different lab groups, institutions, or journals can be referenced, reused, and remixed while maintaining proper attribution and structure.

Figure 4:Example of how machine-readable AST enables cross-page and cross-project hover references. In this abstract example we demonstrate how the source content of a page (page1.md) is parsed into an AST (page1.json) with a unique label called my-label. A second page (page2.md) references this label. At rendering time (page2.html) the content of the label is pulled into the page and displayed via a hover-pop-up.

3.3.3The MyST Specification is a versioned, community-governed standard¶

Just as the Jupyter Notebook format (.ipynb) has enabled interoperability across dozens of tools by serving as a stable, well-defined format, the MyST AST aims to serve a similar role for scientific communication.

The AST specification is versioned and documented, and efforts are underway to standardize it further via the myst-spec initiative.

We are also investing in forward-and-backwards interoperability in this specification in the MyST Document Engine.

By creating a community process for defining the evolution of the MyST Document and Markdown standards, we aim to create a participatory process to ensure that this ecosystem continues to serve the needs of its key stakeholders: members of open science, open source, and open knowledge communities who are passionate about communicating with computational narratives. Coupled with the dependability of a stable specification, and a technology stack that allows for graceful upgrading and downgrading, this allows developers, publishers, and downstream platforms to build confidently on top of the MyST ecosystem.

3.4Computation should be first-class¶

A key challenge in communicating with data lies in the fact that tools and systems for communicating are separate from tools for making discoveries with data and computation. Many researchers begin their communication journey in a computational notebook—exploring data, testing hypotheses, or sharing early-stage insights. Bringing that work into a readable, shareable, and publishable format traditionally requires significant rework: copying plots into a document, cleaning outputs, manually formatting results, re-structuring to suit publication format requirements. These extra steps not only introduce friction, but also weaken reproducibility and create a disconnect between the computation and its communication.

3.4.1Execution and caching are built into the MyST Document Engine¶

MyST comes with infrastructure to parse computational content, execute it[8], cache the results, and insert them into the MyST AST so that they may be used and referenced. Computational content can come in two forms:

- Jupyter Notebooks (

.ipynbfiles)¶ - This is the standard structure for Jupyter Notebooks, and the MyST Document Engine will use the Jupyter kernel metadata in the notebook to execute each cell and embed its content in the output.

- MyST Markdown Notebooks (

.mdfiles)¶ - The MyST Engine allows authors to define the structure of a Jupyter Notebook with a Markdown file, using a special directive called

{code-cell}. Paired with text-to-notebook conversion tools like Jupytext, this allows for two-directional conversion between.ipynbfiles and MyST Markdown Notebooks.

3.4.2Computational outputs are treated like any other content¶

Aside from simply executing and inserting outputs into a MyST document, these outputs can also be used similar to any other type of MyST content.

For example, authors can attach a label to a notebook cell in order to reference its outputs like they would any other kind of content.

For example, the {code-cell} directive below creates a plot with matplotlib in computational-page.md:

(full-plot-context)=

This code generates an image:

```{code-cell} python

:label: my-plot

plt.scatter([1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6])

```In another-page.md, the author is able to insert this output into a figure with a caption like so:

Below you see the results of my computation:

:::{figure} #my-plot

Here's a caption for the image referenced by `my-plot`, see [the full plot context](#full-plot-context) for details.

:::Our goal with Jupyter Book 2 is to integrate computational content at every level. Code, figures, outputs, and interactive elements are embedded directly in the narrative and treated as primary content—not sidebars or supplemental material. This increases the likelihood that authors will interweave computational content into the reading experience, increases the reproducibility and re-usability of computational ideas, and allows for more powerful storytelling through computation, data, and software Granger & Perez, 2021.

3.4.3In-page computation brings computational interactivity to the reading experience¶

Beyond static computational outputs, JB2 embraces the web-native workflows of modern data science by allowing computation to power interactive experiences with a live kernel. Executable content can be powered by any Jupyter Kernel by leveraging MyST’s native integration with Thebe, which enables static documents to become interactive by linking code cells with a computational kernel. Thebe can leverage kernel providers from sources like Binder Jupyter et al., 2018, JupyterHub, or a local Jupyter Server, allowing readers to rerun computations on demand, right from the page without leaving the context of the narrative.

Providing computational interactivity without leaving the page drastically reduces the friction required to interact with computational ideas. It gives authors the ability to power their computational content with arbitrary software, computational resources, or access to data (for example, authors could leverage a service that operates a BinderHub that provides access to GPUs and a 10 Terabyte dataset, and provide interactive kernels for their readers that are powered by that hub). Moreover, modern efforts to package computational environments in web-native toolchains like WebAssembly (via tools like JupyterLite) will allow for interactive execution directly in a reader’s browser.

Figure 5:Embedded notebook cells with live computation directly in an articles with computation backed by Jupyter. These can be running on BinderHub or directly in your browser through JupyterLite. Originally published in Cockett et al. (2024).

3.5Open science infrastructure should be governed by an open community¶

Finally, we believe it is crucial for open science technology and standards to be governed and led by a community of stakeholders, not driven by a single person or organization. Jupyter Book and MyST are community-led projects, developed and governed by an open community of contributors, and hosted under the umbrella of Project Jupyter. The tools in the Jupyter Book 2 stack are maintained by a contributor community that includes open infrastructure organizations, universities, independent developers, and end-users who rely on them in practice.

To facilitate participatory and collaborative design as the Jupyter Book 2 ecosystem evolves, all team practices and policies are defined in the Jupyter Book Team Compass, which inherits its open governance and practices from Project Jupyter. The contributing guide provides detail of the overall stack to help others understand and participate in the development. The MyST Enhancement Proposal process facilitates community feedback to evolve the MyST Specification and Markdown language. These practices aim to allow the MyST ecosystem to remain a community-supported standard while continuing to evolve to meet the needs of its users.

3.6Next directions for Jupyter Book 2¶

This article describes the high level architecture, goals, and guiding principles for the JupyterBook project; there is still much work to be done to fully realize our ambitions. We have tried to make it clear where our goals are still aspirational, and we invite others to join our community as we develop these ideas further.

There are several directions where we are particularly excited to make improvements.

We aim to lean further into the idea of modular and composable content by providing directives and roles that create summaries and views of MyST content. This could be used to create summary content like galleries and blogs with local or remote MyST documents and Jupyter Books. We wish to add support for API documentation to enable software development documentation. We aim to improve integration of computational workflows with external services and infrastructure such as JupyterHub or Binder to allow authors to leverage extra resources or sources of data as part of generating their books. Finally, we aim to enable more extension points in the underlying MyST Engine to give authors and developers more control over the outputs, look and feel, and new kinds of functionality that MyST can support.

4Comparison to Other Tools¶

Jupyter Book 2 sits among a number of tools for authoring and publishing computational and scientific content. These include static site generators, document converters, and academic publishing frameworks. Many of these systems are well-suited to particular workflows—whether technical documentation, reproducible research, or educational materials—but often focus on specific output formats, assume linear document structures, or lack integration with browser-based and computational environments. Moreover, most document engines are produced by a single person or organization, rather than a multi-stakeholder community. JB2 is designed to address these gaps, particularly for communities working in open science.

Jupyter Book 1, developed by the Executable Books Project, is built on Sphinx, a Python documentation generator that enabled integration with reStructuredText, MyST extensions, and a range of HTML output themes. While powerful and extensible, Sphinx was originally designed as a documentation engine for software projects. Support for scientific markup and computation has been added by the community, extending its original design. However, its design principles and architecture are not optimized for the browser-based authoring, computation, content re-use, and efficient multi-output exporting workflows that are core to the JB2 stack.

Jupyter Notebooks, developed by Project Jupyter, is a document format and web-based interface for authoring computational narratives with data.

Jupyter Notebooks have support for interactive outputs and computation that is similar to Jupyter Book.

However, they focus on individual documents rather than multi-page projects with references between them.

They are also designed for data science and exploration rather than communicating more complex and re-usable computational narratives.

Jupyter Book 2 complements the Jupyter Notebook by providing a more rich feature set and workflow that focuses on authoring and reading documents.

A Jupyter Book can be written as a collection of Jupyter Notebooks, and knows how to parse MyST Markdown in notebook cells.

Jupyter Notebooks and Jupyter Lab can also incorporate some of Jupyter Book 2’s functionality into their interfaces via the jupyterlab-myst extension.

Quarto, developed by Posit PBC, is a flexible publishing system supporting Jupyter notebooks, Markdown, and multiple output formats including HTML, PDF, DOCX, and JATS. Quarto is built on top of Pandoc and is tightly integrated with the R, RStudio, and Positron ecosystems. At this time, Quarto is more polished and further in its development lifecycle, with better support for features like PDF rendering (e.g., sub-figures and tables), and presentation output formats. While Quarto has excellent support for static HTML outputs, it does not focus on the principles of modularity and composability which are core to Jupyter Book 2 (e.g., it does not have content APIs and structured build outputs meant for reuse, nor expose packages that can be used by other tools). Quarto is built directly on Pandoc, which uses a GPLv2 license; the Quarto command line tool is MIT licensed since version 1.4, however, many of the core packages, extensions, and utilities are not permissively licensed. Finally, Quarto is developed by a single company, in contrast to Jupyter Book which is governed and developed by a multi-stakeholder community, and uses a permissive MIT license to maximize the re-use of its technology for individual and commercial purposes.

Other documentation and markup systems like Docusaurus, MkDocs, Hugo, quarkdown, typst, and djot are popular choices for technical documentation, developer blogs, PDF generation, and websites. These tools offer good performance, templating, and theming options, and in some cases also focus on extensibility. They are not designed for scientific publishing or computational narratives and they lack features such as executable content, math, and citation handling, semantic metadata, or integrating with persistent identifiers in the scholarly ecosystem (e.g., DOIs, RRIDs, or RORs) - all of which are built into the JB2 ecosystem.

While these tools each serve their respective audiences well, JB2 is focused specifically on the needs of computational and scientific communities. It supports both narrative and executable content, prioritizes open infrastructure and interoperability, and is designed to integrate with existing Jupyter workflows and the wider open-science ecosystems.

5Case Studies¶

Jupyter Book 2 is already being used across a broad range of scientific and educational projects. From national training initiatives to domain-specific research platforms, these case studies demonstrate how JB2 supports reproducible publishing, modular content reuse, and scalable collaboration.

The Turing Way The Turing Way Community, 2025 is an open guide to reproducible, ethical, accessible, and inclusive data science. With hundreds of contributors and a highly active community, the project has adopted Jupyter Book 2 to manage its growing library of community-authored chapters and living documents. The structured document model and improved metadata handling in JB2 have made it easier for the Turing Way’s community members to learn from, reference, and leverage one another’s work. The move from Sphinx to MyST has greatly simplified the technology underlying The Turing Way, which makes it easier for new contributors to build the Turing Way locally and contribute to it. They have been able to reduce the complexity of their own infrastructure by implementing custom features as MyST plugins. This has simplified the book’s deployment process and better allowed these features to be shared as modular, generic plugins rather than Turing-Way-specific scripts.

Project Pythia Rose et al., 2023 is a community-driven effort to advance computational geoscience education, training, and knowledge-sharing through open-source learning materials. Pythia’s collection of cross-referenced Jupyter Book sites draw from over 75 repositories and large numbers of contributors, making the structured content model and cross-repository referencing features of JB2 particularly valuable. Pythia recently transitioned to JB2. There were two standout features to the community: (1) the ability to compose and share configuration between sites, including things like footers, shared references, navigation links; and (2) the ability to cross-reference content between un-related projects. Both of these build on the composability and modularity designs that are at the core of JB2. As an inclusive open-geoscience community effort, Project Pythia aims to build tools and practices that reduce participation barriers and incentivize working geoscientists to share their discipline-specific data fluency. Shared configurations in JB2 substantially reduce the boilerplate code in individual repositories, clearing the way for contributors to focus on their science content while a core team of maintainers efficiently advances the shared computational and web-publishing infrastructure.

The QIIME 2 Framework (Q2F) is a platform for biological data science tools, originally developed for the QIIME 2 microbiome bioinformatics toolkit, but now supporting tools across diverse subdomains of biology including multiplexed serology and pathogen genomics. Q2F has adopted JB2 to support its documentation ecosystem which includes documentation that is general to users of all Q2F-based tools (e.g., creating and using a Q2F data artifact cache) and documentation that is specific to subdomains (e.g., an end-to-end tutorial for microbiome data analysis). JB2 enables embedding of content across documentation projects, such that general content can be embedded in domain-specific content where relevant, making it easier to hide the software stack complexity from end users while avoiding duplication of source content.

QuantEcon provides open educational resources in economics and quantitative methods, built using Python, Julia, and Jupyter.

The transition to JB2 included investment in a custom theme for JupyterBook, which allowed the project to modernize its publishing infrastructure while maintaining interactive notebooks and supporting export to multiple formats including HTML, PDF, and .ipynb.

The upgraded theme allowed for adoption of new features like hover cross-reference between exercises and solutions using the proof and exercise extensions.

These case studies demonstrate the flexibility of JB2 to meet the needs of both education and research, large and small teams, and varied technical audiences. Each project benefits from the same core strengths: modular content, structured metadata, and tight integration with Jupyter.

6Conclusion¶

Jupyter Book 2 is an open-source publishing system for computational and scientific content. It enables authors to combine Markdown, notebooks, structured metadata, and executable code into documents that can be rendered as websites, PDFs, JATS XML, Word documents, and more. By rebuilding the system around a structured document model and a web-native engine, MyST Document Engine, JB2 supports workflows that are modular, reproducible, and extensible. These qualities are essential for modern research and education, and bridge the gap between exploratory computation and formal, published communication, enabling authors to spend more time on data-driven discovery and communicating ideas, and less time re-purposing their workflows for publication.

Unlike general-purpose documentation systems, static website builders, or single-format converters, Jupyter Book 2 is built by and for researchers, educators, and institutions working with code, data, and narrative. Each page produced with JB2 has a structured, machine-readable representation that can be queried, embedded, or reused via an API. This enables a federated publishing model, where content from different projects, lab groups, or institutions can be referenced, previewed, and composed together—without duplication or loss of structure. The result is a more connected and discoverable ecosystem of scientific knowledge, where modular content can be maintained in place but surfaced in multiple contexts, with proper attribution and rich metadata preserved.

The Jupyter Book project is openly governed under Project Jupyter, actively maintained, and already powers many high-impact documentation and communication initiatives across domains. From reproducible data science guides like The Turing Way, to educational curricula like QuantEcon and Project Pythia, to domain-specific platforms like the QIIME 2 Framework, Jupyter Book 2 is helping authors publish richer, more reusable, and more transparent scientific outputs.

As scientific publishing continues to evolve, Jupyter Book offers a model for infrastructure that is interoperable, open by design, and responsive to the needs of its users. It is not just a tool for building books—it is a foundation for the next generation of computational publishing.

Jupyter Book has been developed over the course of nearly a decade, with contributions from dozens of individuals and organizations. We are grateful to the many collaborators, maintainers, and community members who have helped shape the project’s evolution - from its early days as a Jekyll-based tool for compiling notebooks into a textbook, through the Sphinx-based Jupyter Book 1 release, and now with the MyST Markdown and MyST Document Engine-based Jupyter Book 2 architecture. This article did not intend to capture those wide-ranging contributions and ideas or fully document the history of the project, but instead focused on the unique contributions of the Jupyter Book 2 stack.

This project has benefited from key financial support from multiple organizations. The development of MyST Markdown, the Executable Books ecosystem, and Jupyter Book 1 was supported by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (Grant #9231). The development of the MyST Document Engine and the re-architecture of Jupyter Book 2 were made possible in-part by funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (Grant #9231), Alberta Innovates, The Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (2i2c, link), and The Navigation Fund (2i2c, The Navigation Fund (2024)). It also included in-kind support from Curvenote, 2i2c, and the broader open-source community. The refactoring of the QIIME 2 Framework documentation ecosystem was supported in part by the NIH National Cancer Institute (Grant 1U24CA248454-01). Project Pythia’s transition to Jupyter Book 2 was supported by the National Science Foundation (awards 2324302, 2324303 and 2324304). Notebooks Now! was supported by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (#19361).

We especially acknowledge Chris Sewell, whose foundational work on the MyST Markdown specification, the Sphinx parser (myst-parser), and the wider Jupyter Book 1 ecosystem in Sphinx.

Chris’s attention to these technical underpinnings laid the groundwork for many of the capabilities now realized in Jupyter Book 2.

In addition, we acknowledge John Stachurski for providing key leadership and securing the original funding that created the Jupyter Book 1 ecosystem built on Sphinx.

We also acknowledge the work of the Executable Books team, the contributors to Jupyter Frontends sub-project, Thebe, and the maintainers of MyST-related tooling and plugins. The ongoing development of Jupyter Book 2 is supported and stewarded by the Jupyter Book Community, and is now a subproject of Project Jupyter.

Authors are in alphabetical order after “Project Jupyter” following Project Jupyter’s approved process for authoring Jupyter related academic papers and aligned with our shared values of inclusivity and generosity in authorship, following clear, explicit criteria for authorship, openness, and personal accountability.

Copyright © 2025 Jupyter et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creators.

There are 18,152 dependencies of JupyterBook (v1 and v2, combined) based on GitHub dependency graph: https://

github .com /jupyter -book /jupyter -book /network /dependents. CommonMark (https://

commonmark .org) is an unambiguous specification for the Markdown language with a formatting test suite. GitHub Flavored Markdown (https://

github .github .com /gfm/), often shortened as GFM, is the dialect of Markdown that is supported for user content on GitHub. The hover-xref project in sphinx was an attempt at doing this

The Jupyter Book team intends to extend computational capabilities to use kernels and execution services that are hosted elsewhere. This will make it possible for the computation in a Jupyter Book to be executed in a remote environment that may have access to more complex resources or sensitive data (for example, as part of a journal publication pipeline for reproducibility).

- API

- Application Programming Interface

- AST

- Abstract Syntax Tree

- DOI

- Digital Object Identifier

- HTML

- Hypertext Markup Language

- ID

- Identifier

- JATS

- Journal Article Tag Suite

- JB2

- Jupyter Book 2

- JSON

- JavaScript Object Notation

- MyST

- Markedly Structured Text

- ORCID

- Open Researcher and Contributor ID

- Portable Document Format

- Q2F

- QIIME 2 Framework

- ROR

- Research Organization Registry

- URL

- Uniform Resource Locator

- XML

- Extensible Markup Language

- Executable Books Community. (2020). Jupyter Book. Zenodo. 10.5281/ZENODO.2561065

- Granger, B. E., & Perez, F. (2021). Jupyter: Thinking and Storytelling With Code and Data. Computing in Science & Engineering, 23(2), 7–14. 10.1109/mcse.2021.3059263

- Thomas, K., Benjamin, R.-K., Fernando, P., Brian, G., Matthias, B., Jonathan, F., Kyle, K., Jessica, H., Jason, G., Sylvain, C., Paul, I., Damián, A., Safia, A., Carol, W., & Team, J. D. (2016). Jupyter Notebooks – a publishing format for reproducible computational workflows. In Positioning and Power in Academic Publishing: Players, Agents and Agendas. IOS Press. 10.3233/978-1-61499-649-1-87

- Cockett, R., Purves, S., Koch, F., & Morrison, M. (2024). Continuous Tools for Scientific Publishing: Using MyST Markdown and Curvenote to encourage continuous science practices. Proceedings of the 23rd Python in Science Conference, 121–136. 10.25080/nkvc9349

- Fernando Pérez. (2025). AGU Notebooks Now! Evaluation. Zenodo. 10.5281/ZENODO.15061830

- Cockett, R., Heagy, L. J., & Oldenburg, D. W. (2016). Pixels and their neighbors: Finite volume. The Leading Edge, 35(8), 703–706. 10.1190/tle35080703.1

- Cockett, R., Babott, C., & Purves, S. (2025). Continuous Science Foundation Workshop — Banff 2025: Shaping the future of scientific communication through Stories, Values, and Movement from Banff. 10.62329/hytv4378

- Jupyter, P., Bussonnier, M., Forde, J., Freeman, J., Granger, B., Head, T., Holdgraf, C., Kelley, K., Nalvarte, G., Osheroff, A., Pacer, M., Panda, Y., Perez, F., Ragan-Kelley, B., & Willing, C. (2018). Binder 2.0 - Reproducible, interactive, sharable environments for science at scale. Proceedings of the 17th Python in Science Conference, 113–120. 10.25080/majora-4af1f417-011

- The Turing Way Community. (2025). The Turing Way: A handbook for reproducible, ethical and collaborative research. Zenodo. 10.5281/ZENODO.3233853

- Rose, B. E. J., Clyne, J., May, R., Munroe, J., Snyder, A., Eroglu, O., & Tyle, K. (2023). Collaborative Research: GEO OSE TRACK 2: Project Pythia and Pangeo: Building an inclusive geoscience community through accessible, reusable, and reproducible workflows. 10.5281/ZENODO.8184298