Codebraid Preview for VS Code: Pandoc Markdown Preview with Jupyter Kernels

Abstract¶

Codebraid Preview is a VS Code extension that provides a live preview of Pandoc Markdown documents with optional support for executing embedded code. Unlike typical Markdown previews, all Pandoc features are fully supported because Pandoc itself generates the preview. The Markdown source and the preview are fully integrated with features like bidirectional scroll sync. The preview supports LaTeX math via KaTeX. Code blocks and inline code can be executed with Codebraid, using either its built-in execution system or Jupyter kernels. For executed code, any combination of the code and its output can be displayed in the preview as well as the final document. Code execution is non-blocking, so the preview always remains live and up-to-date even while code is still running.

Introduction¶

Pandoc MacFarlane, 2006 is increasingly a foundational tool for creating scientific and technical documents. It provides Pandoc’s Markdown and other Markdown variants that add critical features absent in basic Markdown, such as citations, footnotes, mathematics, and tables. At the same time, Pandoc simplifies document creation by providing conversion from Markdown (and other formats) to formats like LaTeX, HTML, Microsoft Word, and PowerPoint. Pandoc is especially useful for documents with embedded code that is executed during the build process. RStudio’s RMarkdown RStudio Inc., 2016 and more recently Quarto RStudio Inc., 2022 leverage Pandoc to convert Markdown documents to other formats, with code execution provided by knitr Xie, 2015. JupyterLab Granger & Pérez, 2021 centers the writing experience around an interactive, browser-based notebook instead of a Markdown document, but still relies on Pandoc for export to formats other than HTML Jupyter Development Team, 2015. There are also ways to interact with a Jupyter Notebook as a Markdown document, such as Jupytext Wouts & Team, 2018 and Pandoc’s own native Jupyter support.

Writing with Pandoc’s Markdown or a similar Markdown variant has advantages when multiple output formats are required, since Pandoc provides the conversion capabilities. Pandoc Markdown variants can also serve as a simpler syntax when creating HTML, LaTeX, or similar documents. They allow HTML and LaTeX to be intermixed with Markdown syntax. They also support including raw chunks of text in other formats such as reStructuredText. When executable code is involved, the RMarkdown-style approach of Markdown with embedded code can sometimes be more convenient than a browser-based Jupyter notebook since the writing process involves more direct interaction with the complete document source.

While using a Pandoc Markdown variant as a source format brings many advantages, the actual writing process itself can be less than ideal, especially when executable code is involved. Pandoc Markdown variants are so powerful precisely because they provide so many extensions to Markdown, but this also means that they can only be fully rendered by Pandoc itself. When text editors such as VS Code provide a built-in Markdown preview, typically only a small subset of Pandoc features is supported, so the representation of the document output will be inaccurate. Some editors provide a visual Markdown editing mode, in which a partially rendered version of the document is displayed in the editor and menus or keyboard shortcuts may replace the direct entry of Markdown syntax. These generally suffer from the same issue. This is only exacerbated when the document embeds code that is executed during the build process, since that goes even further beyond basic Markdown.

An alternative is to use Pandoc itself to generate HTML or PDF output, and then display this as a preview. Depending on the text editor used, the HTML or PDF might be displayed within the text editor in a panel beside the document source, or in a separate browser window or PDF viewer. For example, Quarto offers both possibilities, depending on whether RStudio, VS Code, or another editor is used.[1] While this approach resolves the inaccuracy issues of a basic Markdown preview, it also gives up features such as scroll sync that tightly integrate the Markdown source with the preview. In the case of executable code, there is the additional issue of a time delay in rendering the preview. Pandoc itself can typically convert even a relatively long document in under one second. However, when code is executed as part of the document build process, preview update is blocked until code execution completes.

This paper introduces Codebraid Preview, a VS Code extension that provides a live preview of Pandoc Markdown documents with optional support for executing embedded code. Codebraid Preview provides a Pandoc-based preview while avoiding most of the traditional drawbacks of this approach. The next section provides an overview of features. This is followed by sections focusing on scroll sync, LaTeX support, and code execution as examples of solutions and remaining challenges in creating a better Pandoc writing experience.

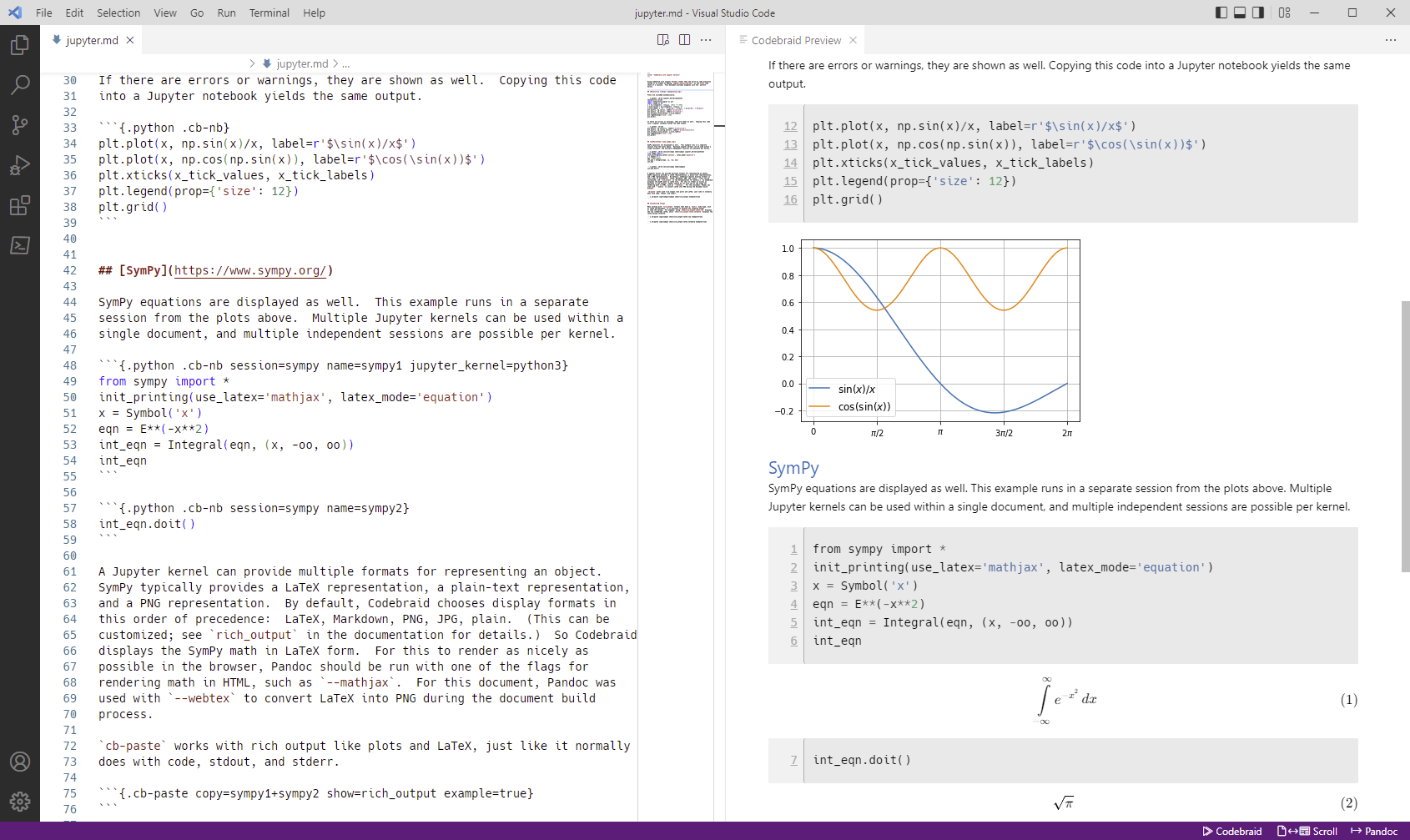

Figure 1:Screenshot of a Markdown document with Codebraid Preview in VS Code. This document uses Codebraid to execute code with Jupyter kernels, so all plots and math visible in the preview are generated during document build.

Overview of Codebraid Preview¶

Codebraid Preview can be installed through the VS Code extension

manager. Development is at

https://

The preview panel can be opened using the VS Code command palette, or by clicking the Codebraid Preview button that is visible when a Markdown document is open. The preview panel takes the document in its current state, converts it into HTML using Pandoc, and displays the result using a webview. An example is shown in Figure 1. Since the preview is generated by Pandoc, all Pandoc features are fully supported.

By default, the preview updates automatically whenever the Markdown source is changed. There is a short user-configurable minimum update interval. For shorter documents, sub-second updates are typical.

The preview uses the same styling CSS as VS Code’s built-in Markdown preview, so it automatically adjusts to the VS Code color theme. For example, changing between light and dark themes changes the background and text colors in the preview.

Codebraid Preview leverages recent Pandoc advances to provide

bidirectional scroll sync between the Markdown source and the preview

for all CommonMark-based Markdown variants that Pandoc supports

(commonmark, gfm, commonmark_x). By default, Codebraid

Preview treats Markdown documents as commonmark_x, which is

CommonMark with Pandoc extensions for features like math, footnotes, and

special list types. The preview still works for other Markdown variants,

but scroll sync is disabled. By default, scroll sync is fully

bidirectional, so scrolling either the source or the preview will cause

the other to scroll to the corresponding location. Scroll sync can

instead be configured to be only from source to preview or only from

preview to source. As far as I am aware, this is the first time that

scroll sync has been implemented in a Pandoc-based preview.

The same underlying features that make scroll sync possible are also used to provide other preview capabilities. Double-clicking in the preview moves the cursor in the editor to the corresponding line of the Markdown source.

Since many Markdown variants support LaTeX math, the preview includes math support via KaTeX Eisenberg & Alpert, 2022.

Codebraid Preview can simply be used for writing plain Pandoc documents. Optional execution of embedded code is possible with Codebraid Poore, 2019, using its built-in code execution system or Jupyter kernels. When Jupyter kernels are used, it is possible to obtain the same output that would be present in a Jupyter notebook, including rich output such as plots and mathematics. It is also possible to specify a custom display so that only a selected combination of code, stdout, stderr, and rich output is shown while the rest are hidden. Code execution is decoupled from the preview process, so the Markdown source can be edited and the preview can update even while code is running in the background. As far as I am aware, no previous software for executing code in Markdown has supported building a document with partial code output before execution has completed.

There is also support for document export with Pandoc, using the VS Code command palette or the export-with-Pandoc button.

Scroll sync¶

Tight source-preview integration requires a source map, or a mapping from characters in the source to characters in the output. Due to Pandoc’s parsing algorithms, tracking source location during parsing is not possible in the general case.[2]

Pandoc 2.11.3

was released in December 2020. It added a sourcepos extension for

CommonMark and formats based on it, including GitHub-Flavored Markdown

(GFM) and commonmark_x (CommonMark plus extensions similar to

Pandoc’s Markdown). The CommonMark parser uses a different parsing

algorithm from the Pandoc’s Markdown parser, and this algorithm permits

tracking source location. For the first time, it was possible to

construct a source map for a Pandoc input format.

Codebraid Preview defaults to commonmark_x as an input format, since

it provides the most features of all CommonMark-based formats. Features

continue to be added to commonmark_x and it is gradually nearing

feature parity with Pandoc’s Markdown. Citations are perhaps the most

important feature currently missing.[3]

Codebraid Preview provides full bidirectional scroll sync between source

and preview for all CommonMark-based formats, using data provided by

sourcepos. In the output HTML, the first image or inline text

element created by each Markdown source line is given an id attribute

corresponding to the source line number. When the source is scrolled to

a given line range, the preview scrolls to the corresponding HTML

elements using these id attributes. When the preview is scrolled, the

visible HTML elements are detected via the Intersection Observer

API.[4] Then their id attributes are used to

determine the corresponding Markdown line range, and the source scrolls

to those lines.

Scroll sync is slightly more complicated when working with output that is generated by executed code. For example, if a code block is executed and creates several plots in the preview, there isn’t necessarily a way to trace each individual plot back to a particular line of code in the Markdown source. In such cases, the line range of the executed code is mapped proportionally to the vertical space occupied by its output.

Pandoc supports multi-file documents. It can be given a list of files to

combine into a single output document. Codebraid Preview provides scroll

sync for multi-file documents. For example, suppose a document is

divided into two files in the same directory, chapter_1.md and

chapter_2.md. Treating these as a single document involves creating

a YAML configuration file _codebraid_preview.yaml that lists the

files:

input-files:

- chapter_1.md

- chapter_2.mdNow launching a preview from either chapter_1.md or

chapter_2.md will display a preview that combines both files.

When the preview is scrolled, the editor scrolls to the corresponding

source location, automatically switching between chapter_1.md and

chapter_2.md depending on the part of the preview that is visible.

The preview still works when the input format is set to a non-CommonMark

format, but in that case scroll sync is disabled. If Pandoc adds

sourcepos support for additional input formats in the future, scroll

sync will work automatically once Codebraid Preview adds those formats

to the supported list. It is possible to attempt to reconstruct a source

map by performing a parallel string search on Pandoc output and the

original source. This can be error-prone due to text manipulation during

format conversion, but in the future it may be possible to construct a

good enough source map to extend basic scroll sync support to additional

input formats.

LaTeX support¶

Support for mathematics is one of the key features provided by many

Markdown variants in Pandoc, including commonmark_x. Math support in

the preview panel is supplied by KaTeX Eisenberg & Alpert, 2022, which is a

JavaScript library for rendering LaTeX math in the browser.

One of the disadvantages of using Pandoc to create the preview is that every update of the preview is a complete update. This makes the preview more sensitive to HTML rendering time. In contrast, in a Jupyter notebook, it is common to write Markdown in multiple cells which are rendered separately and independently.

MathJax MathJax, 2009 provides a broader range of LaTeX support than KaTeX, and is used in software such as JupyterLab and Quarto. While MathJax performance has improved significantly since the release of version 3.0 in 2019, KaTeX can still have a speed advantage, so it is currently the default due to the importance of HTML rendering. In the future, optional MathJax support may be needed to provide broader math support. For some applications, it may also be worth considering caching pre-rendered or image versions of equations to improve performance.

Code execution¶

Optional support for executing code embedded in Markdown documents is provided by Codebraid Poore, 2019. Codebraid uses Pandoc to convert a document into an abstract syntax tree (AST), then extracts any inline or block code marked with Codebraid attributes from the AST, executes the code, and finally formats the code output so that Pandoc can use it to create the final output document. Code execution is performed with Codebraid’s own built-in system or with Jupyter kernels. For example, the code block

```{.python .cb-run}

print("Hello *world!*")

```would result in

Hello world!

after processing by Codebraid and finally Pandoc. The .cb-run

is a Codebraid attribute that marks the code block for execution and

specifies the default display of code output. Further examples of

Codebraid usage are visible in Figure 1.

Mixing a live preview with executable code provides potential usability and security challenges. By default, code only runs when the user selects execution in the VS Code command palette or clicks the Codebraid execute button. When the preview automatically updates as a result of Markdown source changes, it only uses cached code output. Stale cached output is detected by hashing executed code, and then marked in the preview to alert the user.

The standard approach to executing code within Markdown documents blocks the document build process until all code has finished running. Code is extracted from the Markdown source and executed. Then the output is combined with the original source and passed on to Pandoc or another Markdown application for final conversion. This is the approach taken by RMarkdown, Quarto, and similar software, as well as by Codebraid until recently. This design works well for building a document a single time, but blocking until all code has executed is not ideal in the context of a document preview.

Codebraid now offers a new mode of code execution that allows a document to be rebuilt continuously during code execution, with each build including all code output available at that time. This process involves the following steps:

- The user selects code execution. Codebraid Preview passes the document to Codebraid. Codebraid begins code execution.

- As soon as any code output is available, Codebraid immediately streams this back to Codebraid Preview. The output is in a format compatible with the YAML metadata block at the start of Pandoc Markdown documents. The output includes a hash of the code that was executed, so that code changes can be detected later.

- If the document is modified while code is running or if code output is received, Codebraid Preview rebuilds the preview. It creates a copy of the document with all current Codebraid output inserted into the YAML metadata block at the start of the document. This modified document is then passed to Pandoc. Pandoc runs with a Lua filter[5] that modifies the document AST before final conversion. The filter removes all code marked with Codebraid attributes from the AST, and replaces it with the corresponding code output stored in the AST metadata. If code has been modified since execution began, this is detected with the hash of the code, and an HTML class is added to the output that will mark it visually as stale output. Code that does not yet have output is replaced by a visible placeholder to indicate that code is still running. When the Lua filter finishes AST modifications, Pandoc completes the document build, and the preview updates.

- As long as code is executing, the previous process repeats whenever the preview needs to be rebuilt.

- Once code execution completes, the most recent output is reused for all subsequent preview updates until the next time the user chooses to execute code. Any code changes continue to be detected by hashing the code during the build process, so that the output can be marked visually as stale in the preview.

The overall result of this process is twofold. First, building a document involving executed code is nearly as fast as building a plain Pandoc document. The additional output metadata plus the filter are the only extra elements involved in the document build, and Pandoc Lua filters have excellent performance. Second, the output for each code chunk appears in the preview almost immediately after the chunk finishes execution.

While this build process is significantly more interactive than what has been possible previously, it also suggests additional avenues for future exploration. Codebraid’s built-in code execution system is designed to execute a predefined sequence of code chunks and then exit. Jupyter kernels are currently used in the same manner to avoid any potential issues with out-of-order execution. However, Jupyter kernels can receive and execute code indefinitely, which is how they commonly function in Jupyter notebooks. Instead of starting a new Jupyter kernel at the beginning of each code execution cycle, it would be possible to keep the kernel from the previous execution cycle and only pass modified code chunks to it. This would allow the same out-of-order execution issues that are possible in a Jupyter notebook. Yet that would make possible much more rapid code output, particularly in cases where large datasets must be loaded or significant preprocessing is required.

Conclusion¶

Codebraid Preview represents a significant advance in tools for writing with Pandoc. For the first time, it is possible to preview a Pandoc Markdown document using Pandoc itself while having features like scroll sync between the Markdown source and the preview. When embedded code needs to be executed, it is possible to see code output in the preview and to continue editing the document during code execution, instead of having to wait until code finishes running.

Codebraid Preview or future previewers that follow this approach may be perfectly adequate for shorter and even some longer documents, but at some point a combination of document length, document complexity, and mathematical content will strain what is possible and ultimately decrease preview update frequency. Every update of the preview involves converting the entire document with Pandoc and then rendering the resulting HTML.

On the parsing side, Pandoc’s move toward CommonMark-based Markdown variants may eventually lead to enough standardization that other implementations with the same syntax and features are possible. This in turn might enable entirely new approaches. An ideal scenario would be a Pandoc-compatible JavaScript-based parser that can parse multiple Markdown strings while treating them as having a shared document state for things like labels, references, and numbering. For example, this could allow Pandoc Markdown within a Jupyter notebook, with all Markdown content sharing a single document state, maybe with each Markdown cell being automatically updated based on Markdown changes elsewhere.

Perhaps more practically, on the preview display side, there may be ways

to optimize how the HTML generated by Pandoc is loaded in the preview. A

related consideration might be alternative preview formats. There is a

significant tradition of tight source-preview integration in LaTeX (for

example, Laurens (2008)). In principle, Pandoc’s sourcepos

extension should make possible Markdown to PDF synchronization, using

LaTeX as an intermediary.

Copyright © 2022 Poore. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

The RStudio editor is unique in also offering a Pandoc-based visual editing mode, starting with version 1.4 from January 2021 (https://

www .rstudio .com /blog /announcing -rstudio -1 -4 /). See for example jgm/pandoc#4565.

The Pandoc Roadmap at https://

github .com /jgm /pandoc /wiki /Roadmap summarizes current commonmark_xcapabilities.For technical details, https://

www .w3 .org /TR /intersection -observer /. For an overview, https:// developer .mozilla .org /en -US /docs /Web /API /Intersection _Observer _API. For an overview of Lua filters, see https://

pandoc .org /lua -filters .html.

- AST

- abstract syntax tree

- GFM

- GitHub-Flavored Markdown

- John MacFarlane. (2006–2022). Pandoc: a universal document converter. https://pandoc.org/

- RStudio Inc. (2016–2020). R Markdown. https://rmarkdown.rstudio.com/

- RStudio Inc. (2022). Welcome to Quarto. https://quarto.org/

- Yihui Xie. (2015). Dynamic Documents with R and knitr. Chapman & Hall/CRC Press.

- Granger, B. E., & Pérez, F. (2021). Jupyter: Thinking and Storytelling With Code and Data. Computing in Science & Engineering, 23(2), 7–14. 10.1109/MCSE.2021.3059263

- Jupyter Development Team. (2015–2022). nbconvert: Convert Notebooks to other formats. https://nbconvert.readthedocs.io

- Marc Wouts, & the Jupytext Team. (2018–2020). Jupyter notebooks as Markdown documents, Julia, Python or R scripts. https://jupytext.readthedocs.io/

- Eisenberg, E., & Alpert, S. (2022). KaTeX: The fastest math typesetting library for the web. https://katex.org/

- Poore, G. M. (2019). Codebraid: Live Code in Pandoc Markdown. In Chris Calloway, David Lippa, Dillon Niederhut, & David Shupe (Eds.), Proceedings of the 18th Python in Science Conference (pp. 54–61). 10.25080/Majora-7ddc1dd1-008

- MathJax. (2009–2022). MathJax: Beautiful and accessible math in all browsers. https://www.mathjax.org/

- Laurens, J. (2008). Direct and reverse synchronization with SyncTEX. TUGBoat, 29(3), 365–371.