CFSpy: A Python Library for the Computation of Chen-Fliess Series

Abstract¶

In this paper, CFSpy a package in Python that numerically computes Chen-Fliess series is presented. The reachable sets of non-linear systems are also calculated with this package. The method used obtains batches of iterated integrals of the same length instead one of at a time. For this, we consider the alphabetical order of the words that index the series. By redefining the iterated integral reading the index word in the opposite direction from right to left, we allow the broadcasting of the computation of the iterated integral to all permutations of a length. Assuming the input is sufficiently well approximated by piecewise step functions in a fine partition of the time interval, the minimum bounding box of a reachable set is computed by means of polynomials in terms of the inputs. To solve the optimization problem, the SciPy library is used.

1Introduction¶

Control systems describe the dynamics of mechanisms driven by an input vector. In engineering, many of these systems are affected by disturbances or are complex enough that a simplified version of the model is used instead. This endows the systems with uncertainty and impairs their safety operations. The reachable set is a tool that helps analyse safety-related properties. For a given final time, it is defined as the set of all outputs as a response of the system to a given set of initial inputs and states. The overestimation of the reachable set is associated to safety and obstable avoidance and the underestimation to the liveness of the system Chen et al., 2015Seo et al., 2019.

Different methodologies are used to compute the reachable set or an approximation of it. Among the most popular techniques are the Hamilton-Jacobi framework (HJ) Bansal et al., 2017Mitchell, 2007Mitchell et al., 2005 which uses game theory between two players where one player drives the system away from the goal while the other moves it towards the goal, contraction-based which uses contraction theory Maidens & Arcak, 2015Bullo, 2022 on the Jacobian of the vector field of the system, set-based that uses different set representations, monotone systems Scott & Barton, 2013Meyer et al., 2019Jafapour et al., 2024, and mixed-monotonicity Coogan, 2020. There is also the simulation-based reachability Fan et al., 2017Huang & Mitra, 2012 and recently Chen-Fliess series (CFS) have been used for this purpose.

An important problem in the computation of the reachable set is the curse of dimensionality. This consists in the increasing of the complexity of the algorithm as the dimension increases. To tackle this in HJ-based methods, in He et al. (2023), the authors use a new approach that requires the definition of an admissible control set to provide control policies that are consistent on the coupled subsystems. This fixes an incosistency issue with the controls called the leaking corner. For set-based methods, the use of zonotopes is known to have low complexity Althoff & Frehse, 2016.

A CFS provides a local representation of the output of a non-linear control-affine system in terms of its input Fliess, 1981. Given its coefficients, the series overlooks the dynamics when computing the output. This is important in cases where the system is unknown or affected by uncertainty. Then the coefficients are learned by using online learning methods Venkatesh et al., 2019. In Perez Avellaneda & Duffaut Espinosa (2022), a version of noncommutative differential calculus was developed to represent the derivative of a CFS. This was used to perform reachability analysis by applying second degree optimization of CFS in Perez Avellaneda & Duffaut Espinosa (2023).

In the present work, CFSpy Perez Avellaneda, 2024, a Python library for the computation of Chen-Fliess series is introduced and it is used to perform reachability analysis of non-linear system by assuming the input functions can be piece-wise approximated. A polynomial of the CFS is obtained and then optimized to get the points of an overstimation of the reachable set. The SciPy package Virtanen et al., 2020 is used to performed the optimization.

The outline of the paper is the following: in Section 2, the preliminary concepts and results in reachability, formal languages and CFS are presented. In Section 3, the algorithms for the computation of the iterated integrals and the lie derivatives are provided which are the components of CFS. Then, the numerical computation of CFS is shown and examples are given. Finally, in Section 5, the conclusions are stated.

2Preliminaries¶

In the current section, we give the definitions and results needed to explain our main contribution: the CFSpy Python package. For this, in Section 2.1, tools from linear algebra and matrix operations are presented to explain the algorithms. In Section 2.2, concepts from formal language theory are presented to characterize CFS which are defined in Section 2.3. These provide a representation of the output of a nonlinear-affine systems in terms of iterated integrals of the input.

2.1Matrix Operations¶

As we will see in Section 3, to avoid computing the components of the CFS one by one, this is, permutation by permutation, we can use matrix operations such as the Kronecker product to represent the stacking of two matrices and the Hadamard product for elementwise computation.

In particular, stacking a matrix vertically times is written in terms of this product and the unitary vector as follows

The next operation is useful to perfom the iterated integration of the inputs represented as matrices.

It will also be useful to define an operator for the vertical stacking of two different matrices.

2.2Formal Language Theory¶

The CFS is indexed by words of any length. Formally, these words are elements of an algebraic structure called a free monoid where the alphabet is a subset that along with the concatenation operation act as the generator. Words are the noncommutative counterpart of monomials and they extend as the basis of polynomials and then to power series. These are important in the theory of CFS since power series are isomorphic to CFS. In the present section, concepts of formal language theory Salomaa, 1973 are presented.

To make notation concise, given the monoid , we write as the concatenation then by the associativity . Thus, the operation is referred to as concatenation. The concatenation of a finite number of elements of is called a word.

A free monoid generated by the set is the monoid of all finite concatenations of the elements of The generating set is called alphabet and its elements letters. Next, we define a function that helps us classify words and define the algorithms in Section 3.

The set of all words of length is written as . Then, we can express . Next, we define the set of formal power series over with indeterminates in .

The set of all power series is denoted .

2.3Chen-Fliess Series¶

CFS has its roots in the works of Chen, 1957 and Fliess, 1981 and provide an input-output representation of nonlinear control-affine system. They are defined in terms of iterated integrals. To identify them with a system, the coefficients are written in terms of Lie derivatives of the vector field. In the current section, The CFS are presented.

We refer to the following set of equations as a nonlinear control-affine system:

where is the vector state of the system, is the control input vector of the system and is the output.

The iterated integral associated with the word index maps each letter of an alphabet with a coordinate of the vector input function and integrates recursively each input coordinate in the order of the letters in the given word. Specifically, we have the following:

The definition of the iterated integral associated to a word is naturally extended to power series in the following manner:

The support of a formal power series is the set of words that have non-null associated coefficients. This is, . Computationally, we work with power series of a finite support. Specifically, CFS truncated to words of length denoted as . This is, the formal power series of the CFS is truncated to words of length and we have

Next, to provide the association of the CFS with a nonlinear control-affine system, we give the defintion of a Lie derivative.

The following result gives the conditions under which a nonlinear system has an input-output representation by CFS.

3Main Results¶

In the current section, the numerical computation of the Chen-Fliess series is addressed. For this, the iterated integral and the Lie derivative are reformulated to allow for easier algorithm implementations. In Section 2.3, they are written recursively. In this section, we changed the direction of the expressions to compute them iteratively. Instead of looking at the definition of the components forwardly, they are rewritten backwardly.

Another aspect of the numerical computation that we describe is how to avoid calculating each component of the Chen-Fliess series word by word. For this, the new definitions are broadcasted to generate batches of a fixed length that will be stacked and multiplied componentwise to obtain the final output. This increases the speed of the algorithms.

3.1Broadcasting¶

Consider the partition of the time interval and the input vector function . To avoid computing each iterated integral one word at the time and, instead, obtain the batch of all words of a fixed length, we need to consider the alphabetical order of the words. First, broadcast the integration of the input function

then broadcast the multiplication by the first component and integrate, this is,

To make notation lighter, we skip the limits of the integrals and their differentials. Repeating the integration process for each of the components and stacking the result, we obtain the array

Notice that is the array of iterated integral of words of length two. Inductively, given the array of iterated integrals of all words in and denote it

we construct the array of iterated integral of words in by broadcasting the multiplication of each component and the integration. This is,

Numerically, this is done as follows. Take the matrix of the partitioned input functions

integrate by taking the cummulative sum of each component of the matrix and multiplying by a given rectangle size

broadcast the multiplication of the first component

repeat for each component of the input and stack them as in equation (17) to obtain the list of for . This is,

This way of computing the iterated integral assumes and takes advantage of the lexicographical order of words. This avoids having to compute the same iterated integrals several times and instead uses the current block of iterated integrals of certain size to compute the whole batch of the iterated integrals of size . The algorithm is given in the next section.

3.2Computation of Iterated Integrals¶

The following provides a different view of Definition 7 that we use later to compute the iterated integrals. Following the notation of the previous section, we have

Algorithm 1 provides the matrix of the stacked iterated integrals. This is the list of iterated integrals associated with words of length less than a certain number . We denote the cummulative sum as in equation (21) and use a negative number in the index to indicate the removal of column of the corresponding matrix.

The Python code of Algorithm 1 is the following:

def iter_int(u,t0, tf, dt, Ntrunc):

import numpy as np

# The NumPy package is used to handle matrix operations.

"""

Returns the list of all iterated integrals of the input u

indexed by the words of length from 1 to Ntrunc.

Parameters:

-----------

u: array_like

The array of input functions u_i: [t0, tf] -> IR, for all i in {1, ..., m}

stacked vertically. Each function has the form u_i = np.array([u_i[0], u_i[1], ..., u_i[N]])

where u_i[0] = u_i(t_0), u_i[1] = u_i(t_0+dt), ..., u_i[N] = u_i(tf), N = int((tf-t0)//dt+1)

and u = np.vstack([u_1, u_2, ..., u_m])

t0: float

Initial point of the time-interval domain of the inputs

tf: float

Final time of the time-interval domain of the inputs

dt: float

The size of the step of the evenly spaced partition of the time-interval domain

Ntrunc: int

The truncation length of the words of the Chen-Fliess series

Sum_{i=0}^Ntrunc Sum_{eta in X^i} (c, eta) E_{eta}[u](t0,tf)

Returns:

--------

list: ndarray

"""

# The input function u which is the first parameter

# is the vertical stacking of the coordinate input functions u_i

# where each u_i is a zero dimensional numpy array of values defined for

# each point of the dicretized time interval t = np.linspace(t0, tf, int((tf-t0)//dt+1)))

# then the length of the partition of time is computed.

length_t = int((tf-t0)//dt+1)

# Safety check to see whether the length of u is equal to int((tf-t0)//dt+1))

if u.shape[1] != length_t:

raise ValueError("The length of the input, %s, must be int((tf-t0)//dt+1) = %s." %(u.shape[1], length_t))

# Generate the discretized time interval

t = np.linspace(t0, tf, length_t)

# The input u_0 associated with the letter x_0 is generated.

u0 = np.ones(length_t)

# The inputs of the system associated with x_1, ..., x_m with the input associated to x_0 vertically are stacked.

# [

# [u_0(t0), u_0(t0+dt), ..., u_0(tf)],

# [u_1(t0), u_1(t0+dt), ..., u_1(tf)],

# .

# .

# .

# [u_m(t0), u_m(t0+dt), ..., u_m(tf)]

# ]

u = np.vstack([u0, u])

# The number of rows which are equal to the number of total input functions is obtained.

num_input = int(np.size(u,0))

# The total number of iterated integrals of word length less than or equal to the truncation length is computed.

# total_iterint = num_input + num_input**2 + ... + num_input**Ntrunc

total_iterint = num_input*(1-pow(num_input,Ntrunc))/(1-num_input)

# This is transformed into an integer.

total_iterint = int(total_iterint)

# A matrix of zeros with as many rows as the total number of iterated integrals and as many columns

# as the elements in the partition of time is computed.

Etemp = np.zeros((total_iterint,length_t))

# Starts the list ctrEtemp such that ctrEtemp[k]-ctrEtemp[k-1] = the number of iterated integrals

# of word length k

# ctrEtemp[0] = 0

# ctrEtemp[k] = num_input + num_input**2 + ... + num_input**k, 1<=k<=Ntrunc

ctrEtemp = np.zeros(Ntrunc+1)

# ctrEtemp[k] = num_input + num_input**2 + ... + num_input**k, 1<=k<=Ntrunc

for i in range(Ntrunc):

ctrEtemp[i+1] = ctrEtemp[i]+pow(num_input,i+1)

# The iterated integrals of the words of length 1, E_{x_i}[u](t0, tf) for all i in {0, ..., m}, are computed.

# First, E_{x_i}[u](t0, tf) for all i in {0, ..., m} are computed

# for all tf neq t0

sum_acc = np.cumsum(u, axis = 1)*dt

# Then the values of E_{x_i}[u](t0, tf) for tf = t0, this is E_{x_i}[u](t0, t0) = 0, are added

# to have E_{x_i}[u](t0, tf) for all tf>=t0

Etemp[:num_input,:] = np.hstack((np.zeros((num_input,1)), sum_acc[:,:-1]))

# The iterated integrals of the words of length k => 1, E_{x_{i_1}...x_{i_k}}[u](t0, tf) for all i_j in {0, ..., m},

# are computed at each iteration.

for i in range(1,Ntrunc):

# start_prev_block = num_input + num_input**2 + ... + num_input**(i-1)

start_prev_block = int(ctrEtemp[i-1])

# end_prev_block = num_input + num_input**2 + ... + num_input**i

end_prev_block = int(ctrEtemp[i])

# end_current_block = num_input + num_input**2 + ... + num_input**(i+1)

end_current_block = int(ctrEtemp[i+1])

# num_prev_block = num_input**i

num_prev_block = end_prev_block - start_prev_block

# num_current_block = num_input**(i+1)

num_current_block = end_current_block - end_prev_block

"""

U_block =

[

u_0

u_0

.

. # u_0 repeats num_input**i times

.

u_0

u_1

u_1

.

. # u_1 repeats num_input**i times

.

u_1

.

. # u_k repeats num_input**i times

.

u_m

u_m

.

. # u_m repeats num_input**i times

.

u_m

]

"""

U_block = u[np.repeat(range(num_input), num_prev_block), :]

"""

prev_int_block =

[

E_{x_0...x_0x_0}[u](t0,tf)

E_{x_0...x_1x_0}[u](t0,tf)

.

. # block with all the num_input**i iterated integrals of words of length i

.

E_{x_m...x_mx_m}[u](t0,tf)

--------------------------

E_{x_0...x_0x_0}[u](t0,tf)

E_{x_0...x_1x_0}[u](t0,tf)

.

. # block with all the num_input**i iterated integrals of words of length i

.

E_{x_m...x_mx_m}[u](t0,tf)

--------------------------

.

.

.

--------------------------

E_{x_0...x_0x_0}[u](t0,tf)

E_{x_0...x_1x_0}[u](t0,tf)

.

. # block with all the num_input**i iterated integrals of words of length i

.

E_{x_m...x_mx_m}[u](t0,tf)

]

In total there are num_input blocks

"""

prev_int_block = np.tile(Etemp[start_prev_block:end_prev_block,:],(num_input,1))

"""

U_block*prev_int_block =

[

u_0(tf)E_{x_0...x_0x_0}[u](t0,tf)

u_0(tf)E_{x_0...x_1x_0}[u](t0,tf)

.

. # block with all the num_input**i iterated integrals of words of length i

.

u_0(tf)E_{x_m...x_mx_m}[u](t0,tf)

--------------------------

u_1(tf)E_{x_0...x_0x_0}[u](t0,tf)

u_1(tf)E_{x_0...x_1x_0}[u](t0,tf)

.

. # block with all the num_input**i iterated integrals of words of length i

.

u_1(tf)E_{x_m...x_mx_m}[u](t0,tf)

--------------------------

.

.

.

--------------------------

u_m(tf)E_{x_0...x_0x_0}[u](t0,tf)

u_m(tf)E_{x_0...x_1x_0}[u](t0,tf)

.

. # block with all the num_input**i iterated integrals of words of length i

.

u_m(tf)E_{x_m...x_mx_m}[u](t0,tf)

]

current_int_block integrates U_block*prev_int_block

"""

current_int_block = np.cumsum(U_block*prev_int_block, axis = 1)*dt

# Stacks the block of iterated integrals of word length i+1 into Etemp

Etemp[end_prev_block:end_current_block,:] = np.hstack((np.zeros((num_current_block,1)), current_int_block[:,:-1]))

itint = Etemp

return itintProgram 1:Python function to compute iterated integrals.

3.3Computation of Lie Derivatives¶

As in the previous section, we take advantage of the lexicographical order of words. Similarly to the stacked list of iterated integrals, Algorithm 2 provides the list of the stacked Lie derivatives:

The Python code of Algorithm 2 is the following:

def iter_lie(h,vector_field,z,Ntrunc):

import numpy as np

import sympy as sp

# The NumPy package is used to handle matrix operations and

# SymPy to compute the partial derivatives of the Lie derivative.

"""

Returns the list of all the Lie derivatives indexed by the words of length from 1 to Ntrunc

Given the system

dot{z} = g_0(z) + sum_{i=1}^m g_i(z) u_i(t),

y = h(z)

with g_i: S -> IR^n and h: S -> IR, S is a subset of IR^n for all i in {0, ..., n}

The Lie derivative L_eta h of the output function h(z) indexed by the word

eta = x_{i_1}x_{i_2}...x_{i_k} is defined recursively as

L_eta h = L_(x_{i_2}...x_{i_k}) (partial/partial z h) cdot g_{i_1}

Parameters:

-----------

h: symbolic

The symbolic function that represents the output of the system.

vector_field: symbolic array

The array that contains the vector fields of the system.

vector_field =

sp.transpose(sp.Matrix([[(g_0)_1, ..., (g_0)_n],[(g_1)_1, ..., (g_1)_n], ..., [(g_m)_1, ..., (g_m)_n]]))

z: symbolic array

The domain of the vector fields.

z = sp.Matrix([z1, z2, ...., zn])

Ntrunc: int

The truncation length of the words index of the Lie derivatives

Returns:

--------

list: symbolic array

"""

# The number of vector fields is obtained.

# num_vfield = m

num_vfield = np.size(vector_field,1)

# The total number of Lie derivatives of word length less than or equal to the truncation length is computed.

# total_lderiv = num_input + num_input**2 + ... + num_input**Ntrunc

total_lderiv = num_vfield*(1-pow(num_vfield, Ntrunc))/(1-num_vfield)

total_lderiv = int(total_lderiv)

# The list that will contain all the Lie derivatives is initiated.

Ltemp = sp.Matrix(np.zeros((total_lderiv, 1), dtype='object'))

ctrLtemp = np.zeros((Ntrunc+1,1), dtype = 'int')

# ctrLtemp[k] = num_input + num_input**2 + ... + num_input**k, 1<=k<=Ntrunc

for i in range(Ntrunc):

ctrLtemp[i+1] = ctrLtemp[i] + num_vfield**(i+1)

# The Lie derivative L_eta h(z) of words eta of length 1 are computed

LT = sp.Matrix([h]).jacobian(z)*vector_field

# Transforms the lie derivative from a row vector to a column vector

LT = LT.reshape(LT.shape[0]*LT.shape[1], 1)

# Adds the computed Lie derivatives to a repository

Ltemp[:num_vfield, 0] = LT

# The Lie derivatives of the words of length k => 1, L_{x_{i_1}...x_{i_k}}h(z) for all i_j in {0, ..., m},

# are computed at each iteration.

for i in range(1, Ntrunc):

# start_prev_block = num_input + num_input**2 + ... + num_input**(i-1)

start_prev_block = int(ctrLtemp[i-1])

# end_prev_block = num_input + num_input**2 + ... + num_input**i

end_prev_block = int(ctrLtemp[i])

# end_current_block = num_input + num_input**2 + ... + num_input**(i+1)

end_current_block = int(ctrLtemp[i+1])

# num_prev_block = num_input**i

num_prev_block = end_prev_block - start_prev_block

# num_current_block = num_input**(i+1)

num_current_block = end_current_block - end_prev_block

"""

LT =

[

[L_{x_0...x_0x_0}h(z)],

[L_{x_0...x_1x_0}h(z)],

.

.

.

[L_{x_m...x_m}h(z)],

]

these are the Lie derivatives indexed by words of length i

"""

LT = Ltemp[start_prev_block:end_prev_block,0]

"""

LT =

[

[partial/ partial z L_{x_0...x_0x_0}h(z)],

[partial/ partial z L_{x_0...x_1x_0}h(z)],

.

.

.

[partial/ partial z L_{x_m...x_m}h(z)],

]

*

[g_0, g_1, ..., g_m]

=

[

L_{x_0x_0...x_0}h(z) | L_{x_0x_0..x_0x_1x_0}h(z) | | L_{x_0x_m..x_mx_m}h(z)

L_{x_1x_0...x_0}h(z) | L_{x_1x_0..x_0x_1x_0}h(z) | | L_{x_1x_m..x_mx_m}h(z)

L_{x_2x_0...x_0}h(z) | L_{x_2x_0..x_0x_1x_0}h(z) | | L_{x_2x_m..x_mx_m}h(z)

. | . | ... | .

. | . | ... | .

. | . | ... | .

L_{x_mx_0...x_0}h(z) | L_{x_mx_0..x_0x_1x_0}h(z) | | L_{x_mx_m..x_mx_m}h(z)

]

"""

LT = LT.jacobian(z)*vector_field

# Transforms the lie derivative from a row vector to a column vector

"""

LT =

[

L_{x_0x_0...x_0}h(z)

L_{x_1x_0...x_0}h(z)

L_{x_2x_0...x_0}h(z)

.

.

.

L_{x_mx_0...x_0}h(z)

------------------------

L_{x_0x_0...x_1x_0}h(z)

L_{x_1x_0...x_1x_0}h(z)

L_{x_2x_0...x_1x_0}h(z)

.

.

.

L_{x_mx_0...x_1x_0}h(z)

------------------------

.

.

.

------------------------

L_{x_0x_m...x_m}h(z)

L_{x_1x_m...x_m}h(z)

L_{x_2x_m...x_m}h(z)

.

.

.

L_{x_mx_m...x_m}h(z)

]

these are the Lie derivatives indexed by words of length i+1

"""

LT = LT.reshape(LT.shape[0]*LT.shape[1], 1)

# Adds the computed Lie derivatives to the repository

Ltemp[end_prev_block:end_current_block,:]=LT

return LtempProgram 2:Python function to compute Lie derivatives.

Notice that the definition of the Lie derivative in Definition 9 does not require a modification since its computation is performed backwards from the last letter of the flipped word to the first letter.

3.4Numerical Computation of Chen-Fliess Series¶

In section Section 3.2, we obtained the iterated integral and in section Section 3.3, the Lie derivative. Alternatively to Definition 8, the CFS is represented as the inner product of the vector with coordinates equal to all the iterated integrals and the vector with coordinates equal to all the Lie derivatives. This is,

We obtain a similar version for the truncated CFS. From this and the previous sections, we have the following approximation of the CFS truncated to word length :

3.5CFSpy Package¶

The CFSpy package is a set of tools implemented in the Python programming language to compute Chen-Fliess series and perform reachability analysis of nonlinear control-affine systems. The package is intended to be as minimal and self-contained as possible as it doesn’t require any other package or software except for NumPy Harris et al., 2020 and SymPy Meurer et al., 2017 used in the computation of the series and for the reachability.

The package consists of the following elements in terms of the system (9):

The function iter_int is the implementation of Algorithm 1 and takes as arguments the discretized input function , the initial and final time , the step size of discretization of the input function and the truncation length of the series. The input is entered as a matrix where the row is the input coordinate and the length of the dicretization if . The output of the function is list of iterated integrals of length less or equal to . The function single_iter_int provides one single iterated integral given the index word as argument.

The function iter_lie is the implementation of Algorithm 2 and takes as arguments the output function , the vector fields , the state variable , and the truncation length of the series. The functions are entered as symbolic functions.

The function pol_inputs is the symbolic version of iter_int that assumes the input functions are constants. It takes a set of symbolic inputs and the truncation length of the series. The output is the list of symbolic commutative monomials of degree less or equal to .

4Simulations¶

In the current section, we use the CFSpy package to simulate the output of a system and analyze the reachability by computing the minimum bounding overestimating box of the set of outputs given a set of inputs to the system.

Consider the Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Recovered-Susceptible (SEIRS) model for infectious disease dynamics Bjørnstad et al., 2020

where represents the susceptible population, , the exposed group, , the infectious population, and the recovered population. The parameter represents the average rate at which an infected individual can infect a susceptible one, is the period an exposed individual stays in that group before becoming infectious. Recovered individuals are immune for an average protected period of . The parameter is the rate at which the infected population dies and is the rate of background death of all the population. The total population in the model is and is the infectious period.

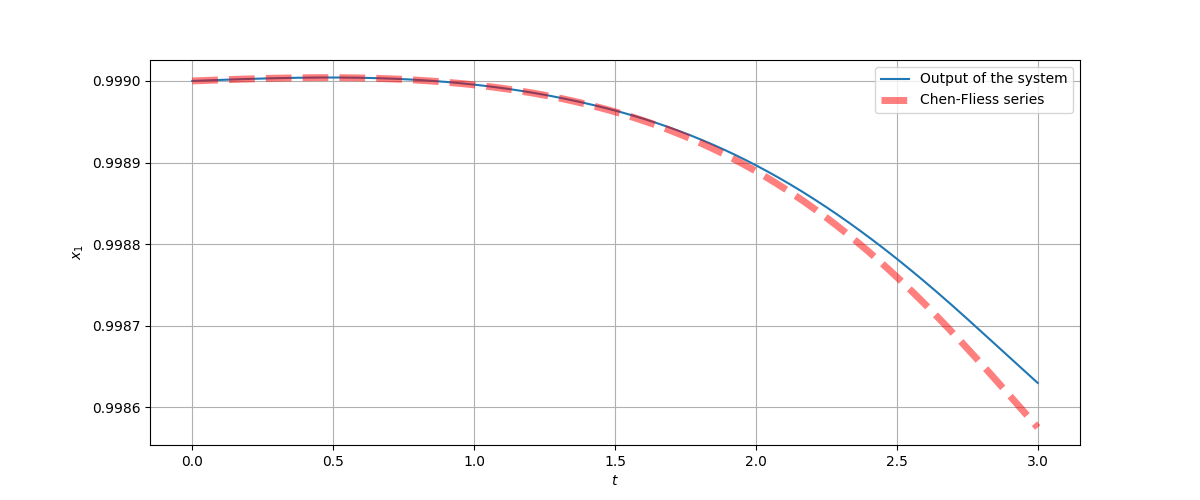

Take the SEIRS model in (28) with control input and and the following parameters: . The system (28) is written as in (9) where . Consider and , and word truncation length of .

Figure 1:The picture shows the susceptible population of the SEIRS model and its approximation by CFS when the fluctuating inputs and enter the system. The CFS is truncated to a word length of . The approximation by CFS performs well before when the series starts to diverge.

The following block of code uses CFSpy to compute the CFS of the SEIRS system having the susceptible population as the output.

from CFS import iter_int, iter_lie, single_iter_int, single_iter_lie

import numpy as np

from scipy.integrate import solve_ivp

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import sympy as sp

mu = 1 / 76

omega = 1

sigma = 1 / 7

alpha = 0

N = 1.0

# Define the SEIRS system

def system(t, x, u1_func, u2_func):

x1, x2, x3, x4 = x

u1 = u1_func(t)

u2 = u2_func(t)

dx1 = mu * N - u1 * x3 * x1 / N + omega * x4 - mu * x1

dx2 = u1 * x3 * x1 / N - sigma * x2 - mu * x2

dx3 = sigma * x2 - u2 * x3 - (mu + alpha) * x3

dx4 = u2 * x3 - omega * x4 - mu * x4

return [dx1, dx2, dx3, dx4]

# Input 1

def u1_func(t):

return np.sin(t)

# Input 2

def u2_func(t):

return np.cos(t)

# Initial condition

x0 = [0.999, 0.001, 0.0, 0.0]

# Time range

t0 = 0

tf = 3

dt = 0.001

t_span = (t0, tf)

# Simulation of the system

solution = solve_ivp(system, t_span, x0, args=(u1_func, u2_func), dense_output=True)

# Partition of the time interval

t = np.linspace(t_span[0], t_span[1], int((tf-t0)//dt+1))

y = solution.sol(t)

# Define the symbolic variables

x1, x2, x3, x4 = sp.symbols('x1 x2 x3 x4')

x = sp.Matrix([x1, x2, x3, x4])

# Define the system symbolically

g = sp.transpose(sp.Matrix([[mu * N + omega * x4 - mu * x1, - sigma * x2 - mu * x2, sigma * x2 - (mu + alpha) * x3, - omega * x4 - mu * x4], \

[-x3 * x1 / N, x3 * x1 / N, 0, 0], [0, 0, - x3, x3]]))

# Define the output symbolically

h = x1

# The truncation of the length of the words that index the Chen-Fliess series

Ntrunc = 6

# Coefficients of the Chen-Fliess series evaluated at the initial state

Ceta = np.array(iter_lie(h,g,x,Ntrunc).subs([(x[0], x0[0]),(x[1], x0[1]), (x[2], x0[2]), (x[3], x0[3])]))

# inputs as arrays

u1 = np.sin(t)

u2 = np.cos(t)

# input array

u = np.vstack([u1, u2])

# List of iterated integral

Eu = iter_int(u,t0, tf, dt, Ntrunc)

# Chen-Fliess series

F_cu = x0[0]+np.sum(Ceta*Eu, axis = 0)

# Graph of the output and the Chen-Fliess series

plt.figure(figsize = (12,5))

plt.plot(t, y[0].T)

plt.plot(t, F_cu, color='red', linewidth=5, linestyle = '--', alpha = 0.5)

plt.xlabel('$t$')

plt.ylabel('$x_1$')

plt.legend(['Output of the system','Chen-Fliess series'])

plt.grid()

plt.show()Program 3:CFS Computation

Consider the SEIRS model (28), with control inputs and . The following code uses SciPy Optimize to compute the reachable set of the susceptible population as the convex line between its minimum and maximum at time .

![The picture shows the MBB of the reachable set of system to inputs \beta \in [0.01, \ 0.7] and \gamma \in [0.03, \ 3] for t= 1s. The CFS is truncated to a word length of N = 6.](https://pub.curvenote.com/0199eb8b-fd5f-7f2b-a1da-384b742d7a72/public/MBB-987dadaa3dceb2c2c25b099b3ca883d0.png)

Figure 2:The picture shows the MBB of the reachable set of system (28) to inputs and for . The CFS is truncated to a word length of .

import numpy as np

import sympy as sp

from CFS import iter_lie, sym_CFS

from scipy.optimize import minimize

from scipy.optimize import Bounds

# Parameters of the model

mu = 1 / 76

omega = 1

sigma = 1 / 7

alpha = 0

N = 1.0

# Initial state

x0 = [0.999, 0.001, 0.0, 0.0]

# Define the symbolic variables

x1, x2, x3, x4 = sp.symbols('x1 x2 x3 x4')

x = sp.Matrix([x1, x2, x3, x4])

# Define the system symbolically

g = sp.transpose(sp.Matrix([[mu * N + omega * x4 - mu * x1, - sigma * x2 - mu * x2, sigma * x2 - (mu + alpha) * x3, - omega * x4 - mu * x4], \

[-x3 * x1 / N, x3 * x1 / N, 0, 0], [0, 0, - x3, x3]]))

# Define the output symbolically

h = x1

# Truncation length for Chen-Fliess series

Ntrunc = 6

# Coefficients of the Chen-Fliess series evaluated at the initial state (using SymPy Matrix)

Ceta = sp.Matrix(iter_lie(h, g, x, Ntrunc)).subs([(x[0], x0[0]), (x[1], x0[1]), (x[2], x0[2]), (x[3], x0[3])])

# Define the input symbols

u0, u1, u2 = sp.symbols('u0 u1 u2')

u = sp.Matrix([u0, u1, u2])

t = sp.symbols('t')

# Compute F_cu with the coefficients and product terms

F_cu = x0[0]+np.sum(sym_CFS(u, t, Ntrunc, Ceta), axis = 0)

# Substitute u0 = 1 and t = 1

F_cu_substituted = sp.Matrix(F_cu).subs({u0: 1, t: 1})

# Display the result after substitution

# Convert symbolic expression to a numerical function using lambdify

sum_T_func = sp.lambdify([u1, u2], sp.Matrix(F_cu_substituted), 'numpy')

# Define the objective function for scipy.optimize

def objective(x):

# x is an array [u1, u2]

return sum_T_func(x[0], x[1])

def objective_max(x):

# x is an array [u1, u2]

return -1*sum_T_func(x[0], x[1])

# Initial guess for u1, u2

u_init = np.array([0.1, 0.1])

# Define the bounds: (0.01<u1<0.7, 0.03<u2<3)

bounds = Bounds([0.01, 0.03], [0.7, 3])

# Minimize the function with constraints

result = minimize(objective, u_init, bounds=bounds)

result_max = minimize(objective_max, u_init, bounds=bounds)

# Print the results

print("Optimal values:", result.x)

print("Minimum value:", result.fun)

print("Optimal values:", result_max.x)

print("Maximum value:", -result_max.fun)Program 4:The reachable set of the susceptible population is obtained by computing its optimal values generated by the inputs and entering the system.

5Conclusions¶

This work presented the CFSpy Python package to numerically compute the Chen-Fliess series and perform reachability analysis. For this, the definition of the iterated integral has been modified similarly to the Lie derivative: iterating the letters of the word backwards instead of forwardly as it is originally defined. The iterated integrals and the Lie derivatives are computed in batches of the same wordth length. Taking advantage of the lexicographical order of the words, the computation of each batch is done recursively. This reduces the computational time compared to the straight forward approach of iterating word by word. The algorithms of the iterated integral and the Lie derivatives are provided as well as their implementation. The functions of the CFSpy package are described. Finally, the SEIRS epidemiological model is used to show the simulations and compare the accuracy of the package.

Copyright © 2025 Avellaneda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- CFS

- Chen-Fliess series

- HJ

- Hamilton-Jacobi framework

- SEIRS

- Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Recovered-Susceptible

- Chen, M., Hu, Q., Mackin, C., Fisac, J. F., & Tomlin, C. J. (2015). Safe Platooning of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles via Reachability. 54th Conf. on Decision and Control, 4695–4701. https://doi.org/10.1109/CDC.2015.7402951

- Seo, H., Lee, D., Son, C. Y., Tomlin, C. J., & Kim, H. J. (2019). Robust Trajectory Planning for a Multirotor Against Disturbance Based on Hamilton-Jacobi Reachability Analysis. Int. Conf. on Intell. Robot. and Syst. https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS40897.2019.8968126

- Bansal, S., Chen, M., and Hebert, S., & Tomlin, J. (2017). Hamilton-Jacobi Reachability: A Brief Overview and Recent Advances. 56th Conf. on Decision and Control, 2242–2253. https://doi.org/10.1109/CDC.2017.8263977

- Mitchell, I. (2007). A Toolbox of Level Set Methods. In UBC Department of Computer Science Technical Report TR-2007-11, vol. 1 (p. 6).

- Mitchell, I., Bayern, A. M., & Tomlin, C. J. (2005). A Time-dependent Hamilton-Jacobi Formulation of Reachable Sets for Continuous Dynamic Games. In Trans. on Automatic Control, Vol 50, No. 7. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.2005.851439

- Maidens, J., & Arcak, M. (2015). Reachability Analysis of Nonlinear Systems Using Matrix Measures. In Trans. on Automatic Control. Vol 60, No. 1 (pp. 265–270). https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.2014.2325635

- Bullo, F. (2022). Contraction Theory for Dynamical Systems, 1.0 ed. (pp. 265–270). Kindle Direct Publishing. http://motion.me.ucsb.edu/book-ctds

- Scott, J. K., & Barton, P. I. (2013). Bounds on the Reachable Sets of Nonlinear Control Systems. In Automatica, Vol. 49, No. 1 (pp. 93–100). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2012.09.020

- Meyer, J. K., Devonport, A., & Arcak, M. (2019). TIRA: Toolbox for Interval Reachability Analysis. 22nd ACM International Conference on Hybrid Systems: Computation and Control, 224–229. https://doi.org/10.1145/3302504.3311808

- Jafapour, S., Harapanahalli, A., & Coogan, S. (2024). Efficient Interaction-aware Interval Analysis of Neural Network Feedback Loops. In Trans. on Automatic Control, Vol. 69, No. 12 (pp. 8706–8721). https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.2024.3420968

- Coogan, S. (2020). Mixed Monotonicity for Reachability and Safety in Dynamical Systems. 59th Conf. on Decision and Control, 5074–5085. https://doi.org/10.1109/CDC42340.2020.9304391

- Fan, C., Kapinski, J., Jin, X., & Mitra, S. (2017). Simulation-driven Reachability Using Matrix Measures. In ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst., Vol. 17, No. 1. https://doi.org/10.1145/3126685

- Huang, Z., & Mitra, S. (2012). Computing Bounded Reach Sets from Sampled Simulation Traces. 15th ACM International Conference on Hybrid Systems: Computation and Control, Ser. HSCC’12, 291–294. https://doi.org/10.1145/2185632.2185676

- He, C., Gong, Z., Chen, M., & Hebert, S. (2023). Efficient and Guaranteed Hamilton–Jacobi Reachability via Self-Contained Subsystem Decomposition and Admissible Control Sets. Control Systems Letters, Vol 7., 3824–3829. https://doi.org/10.1109/LCSYS.2023.3344659

- Althoff, M., & Frehse, G. (2016). Combining zonotopes and support functions for efficient reachability analysis of linear systems. 55th Conference on Decision and Control, 7439–7446. https://doi.org/10.1109/CDC.2016.7799418