Extension of the OpenMC depletion module for transport-independent depletion

Abstract¶

We have added functionality for running depletion simulations independently of neutron transport in OpenMC, an open source Monte Carlo particle transport code with an internal depletion module. Transport-independent depletion uses pre-computed static multigroup cross sections and fluxes to calculate reaction rates for OpenMC’s depletion matrix solver. This accelerates the depletion calculation, but removes the spatial coupling between depletion and neutron transport.

We used a simple PWR pincell to validate the method against the existing transport-coupled depletion method. Nuclide concentration errors roughly scale with depletion time step size and are inversely proportional to the amount of the nuclide present in a depletable material. The magnitude of concentration error depends on the nuclide of interest. Concentration errors for low-abundance nuclides at longer (30-day) time steps exhibit large negative initial concentration the becomes more positive with time due to overestimation of nuclide production stemming from the lack of spatial coupling to neutron transport. For ten 3-day time steps, fission product concentration errors are all under 3%. Actinide concentration errors range from 10-15% for Am and Cm, 5-7% for Pu and Np, and 2% and less for U. Surprisingly, the numbers are similar for 30-day time steps. These results demonstrate the potential of this new method with moderate accuracy and extraordinary time savings for low and medium fidelity simulations. Concentration error characterization on larger models remains an open area of interest.

1Introduction¶

Accurate simulations of advanced reactors on exascale computing hardware requires state-of-the-art software tools in Monte Carlo transport and heat-coupled computational fluid dynamics Romano et al., 2021Merzari et al., 2023. These methods are computationally expensive, but deliver high confidence in their results. If any component in this tool chain could be simplified or sped up, it would reduce the computational cost on and economic cost from these exascale machines. For Monte Carlo neutron transport, depletion simulations are one of the more expensive simulations. Depletion is the process by which the nuclide composition changes due to nuclear transmutation and decay reactions occurring in a material subject to irradiation. Depletion capabilities were recently added Romano, 2021 to OpenMC Romano et al., 2015, an open source, community developed Monte Carlo particle transport code. The depletion solver utilizes OpenMC’s Python API to iteratively run a transport simulation, calculate transmutation reaction rates, solve the depletion matrix (Eq. 2), and update the material composition. This makes transport-coupled depletion calculations computationally expensive, especially for large reactor models.

In the present work, we describe a new method for running depletion calculations without the need to iteratively run transport calculations by using pre-calculated microscopic cross sections and fluxes for each depletion step. At most, only one transport calculation needs to be run to generate these cross sections and fluxes. Neutron transport and depletion are tightly coupled because the change in material composition can result in changes to the spatial distribution of reaction rates. If few materials are used in a transport-independent depletion calculation, this effectively removes spatial effects of the changing material composition due to the static fluxes and cross sections.

This limits the practical application of transport-independent depletion to domains where capturing spatial effects are a secondary concern. One such application is in global fuel-cycle analysis where we are more concerned with the overall change in material composition. Fuel cycle simulations typically model many different reactors simultaneously over long time periods. The capabilities described in this paper have been utilized in Cyclus Huff et al., 2016 -- an open source fuel cycle simulator -- for coupling depletion to the fuel cycle simulaton Bachmann et al., 2024. Another area of application is in facilities where the coupling between neutron transport and depletion is effectively one-way. This is often the case for experimental facilities with a neutron source where the source rate is high enough to cause activation of materials but not high enough to produce meaningful burnup of materials. Many proposed fusion energy facilities would fall into this category. For such applications, it is unnecessary to run a fully coupled simulation between neutron transport and depletion; instead, a neutron transport simulation corresponding to the beginning of irradiation can determine reaction rates relative to the neutron source rate, and then the depletion calculation can be performed using the reaction rates scaled by any changes in the neutron source rate over time. For fusion systems, these calculations are often carried out with FISPACT-II Sublet et al., 2017; See Eade et al., 2020 for a recent example. The capabilities described in this paper have also been utilized for a recent study of shutdown dose rate in fusion systems Peterson et al., 2024.

This paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we describe the methods and algorithms used to calculate reaction rates using the new depletion capabilities. In Section 3, we describe our simulation and analyze the results. In Section 4, we summarize our results, and discuss some gaps in the current implementation of the new feature.

2Methods¶

Depletion is typically done in sub-regions that are small enough to have little spatial variation in the flux (and hence in the reaction rates). For example, in a model of a full reactor core, depletion regions may correspond to individual fuel pins, or even smaller sub-pin regions of radial rings and azimuthal segments. The general form of the equation governing depletion is

where

The summations in Equation (1) are effectively over all nuclides except , as and must be zero by definition. Equation (1) can be condensed into a matrix-vector equation:

where

and is the depletion matrix containing the decay and transmutation coefficients. The coefficients of change with time and depend on the nuclide composition vector , making this a nonlinear system of equations. OpenMC utilized the CRAM method to solve this system of equations Romano, 2021.

We had two design goals for transport-independent depletion functionality:

Enable use of OpenMC depletion capabilities using only the Python API

Enable depletion of materials directly given a multi-group flux for each material.

We created the IndependentOperator and MicroXS classes to

achieve these design goals.

2.1MicroXS¶

The MicroXS class contains cross section data indexed by nuclide,

reaction name, and energy group. It also contains methods to import and

export MicroXS objects from .csv files. In principle, a

user could create multi-group microscopic cross sections with a

transport solver code, and then use the MicroXS class to read in

the cross section data for use in depletion. However, this is

unnecessary as the get_microxs_and_flux() function runs an OpenMC

-eigenvalue calculation to create a MicroXS object and

multi-group flux profile for each user-specified domain.

In the initial release of this feature in OpenMC v0.13.1, MicroXS

sub-classed the pandas.DataFrame. class to store data and assumed a

one-group structure. The v0.14.0 release removed the pandas dependency

and refactored MicroXS class to store multi-group cross section

data.

2.2IndependentOperator¶

The Operator class contains data and methods for running

transport-coupled depletion calculations and runtime processing of

OpenMC statepoint files to extract the data needed to solve Equation

(2). In this work, we refactored the

Operator class into a CoupledOperator class maintaining

the existing depletion capability. We implemented the

transport-independent depletion machinery in a new class,

IndependentOperator which uses an instance of the MicroXS

class and corresponding fluxes for each depletion domain to calculate

reaction rates for that domain using multi-group microscopic cross

sections.

Calculating reactions rates using multi-group cross sections is mathematically equivalent to tallying the reaction rates directly. In transport-coupled depletion calculation, the transmutation reaction rates are tallied directly as:

where and indicate the nuclide and reaction, respectively.

To perform depletion using multi-group cross sections, the multi-group cross sections and fluxes are multiplied to get a per-source neutron reaction rate:

In practice, this introduces a discretization error, but in the limit of infinitely small energy groups, Equation (5) is equivalent to Equation (4). To get a time-dependent microscopic cross section or flux, we must perform transport calculations (and in the case of time-varying microscopic cross sections, incorporate thermal feedbacks). Herein lies the primary assumption of transport-independent depletion: microscopic cross sections and reactor fluxes are static.

Both the tallied and multi-group-calculated reaction rates have units of . A normalization factor in is applied to obtain the more conventional unit of :

This normalization factor is typically related to the power of the

reactor and energy released from fission (fission-q

normalization) or the external source strength (source-rate

normalization). IndependentOperator may use either of these methods to normalize

the reaction rates. While CoupledOperator may use several methods to

calculate fission yields, including using the Monte Carlo simulation to

directly tally fission yields, IndependentOperator relies on

constant yield data included in the depletion chain file.

3Results¶

To validate transport-independent depletion, we ran depletion simulations on a PWR with a single depletion zone for three cases:

Transport-coupled depletion,

Transport-independent depletion,

Transport-independent depletion with microscopic cross sections updated after each depletion step.

The first case serves as a reference solution we use to estimate the error in the solution of the new method. We used 25 inactive and 125 active batches, with 106 particles per batch. For the second case, we used three different group structures to test the effect on solution accuracy: one group, CASMO-8, and CASMO-40. The third case is much slower than the first case as the cross sections need to be reloaded after each depletion step. The third case is a sanity check that the cross sections are being computed correctly, as it should have a smaller error than the second case. Due to the cross section discretization that occurs before performing depletion, we do not expect the third case results to converge to the first case results in limit of infinite particles, but we would expect it to converge in the limit of infinite particles and energy groups. The third case was only run for one-group transport-independent depletion.

Table 1 and Table 2 contain the material parameters and compositions of our model, and Table 3 contains the geometric parameters. We used the ENDF/B-VII.1 nuclear data library available at openmc.org/data. We used the ENDF/B-VII.1 depletion chain in the PWR spectrum also available at openmc.org/data.

Table 1:Material Parameters

| Item | Fuel | Cladding | Water |

| Density [g cm] | 10.4 | 6 | 1.0 |

| Volume [cm] | 0.1764 | – | – |

| S(,) | – | – | ‘c_H_in_H2O‘ |

Table 2:Material Compositions

| Fuel composition | Cladding composition | Water composition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclide | Composition [atom %] | Nuclide | Composition [atom %] | Nuclide | Composition [atom %] |

| 15O | 0.000758 | 90Zr | 0.5145 | 1H | 1.999689 |

| 16O | 1.999242 | 91Zr | 0.1122 | 2H | 0.000311 |

| 234U | 0.000385 | 92Zr | 0.1715 | 15O | 0.999621 |

| 235U | 0.043020 | 94Zr | 0.1738 | 16O | 0.000379 |

| 236U | 0.000197 | 96Zr | 0.028 | ||

| 238U | 0.956398 | ||||

Table 3:Geometric Parameters

| Fuel Radius [cm] | Clad Radius [cm] | Water Bounding Box dimensions [cm cm] |

| 0.42 | 0.45 | 1.24 1.24 |

Depletion is a slow process whose effects on neutronics only start to apply

on longer timescales (days and months). For validation purposes we ran each

of the three cases with four different magnitudes of timestep size: 360

seconds, 4 hours, 3 days, and 30 days. All simulations ran for 10 depletion

steps. We used the PredictorIntegrator time stepper, which is

analogous to the Euler method. Predictor-corrector methods are not useful

for transport independent depletion. The correction step will utilize the

same reaction rates as the initial prediction due to the static fluxes and

cross sections. This means any predictor-corrector method will produce the

same numerical results as a predictor method but with higher floating-point

errors due to the increased number of operations [1]. We used constant

reaction rate Q values multiplied by the reaction rates to obtain the

normalization factor (fission-q normalization) for all cases with

a linear power density of 174 W/cm.

The general trend in our results is that concentration errors are smaller for shorter depletion time steps, and larger for longer depletion time steps, however some nuclides exhibit more complicated behavior.

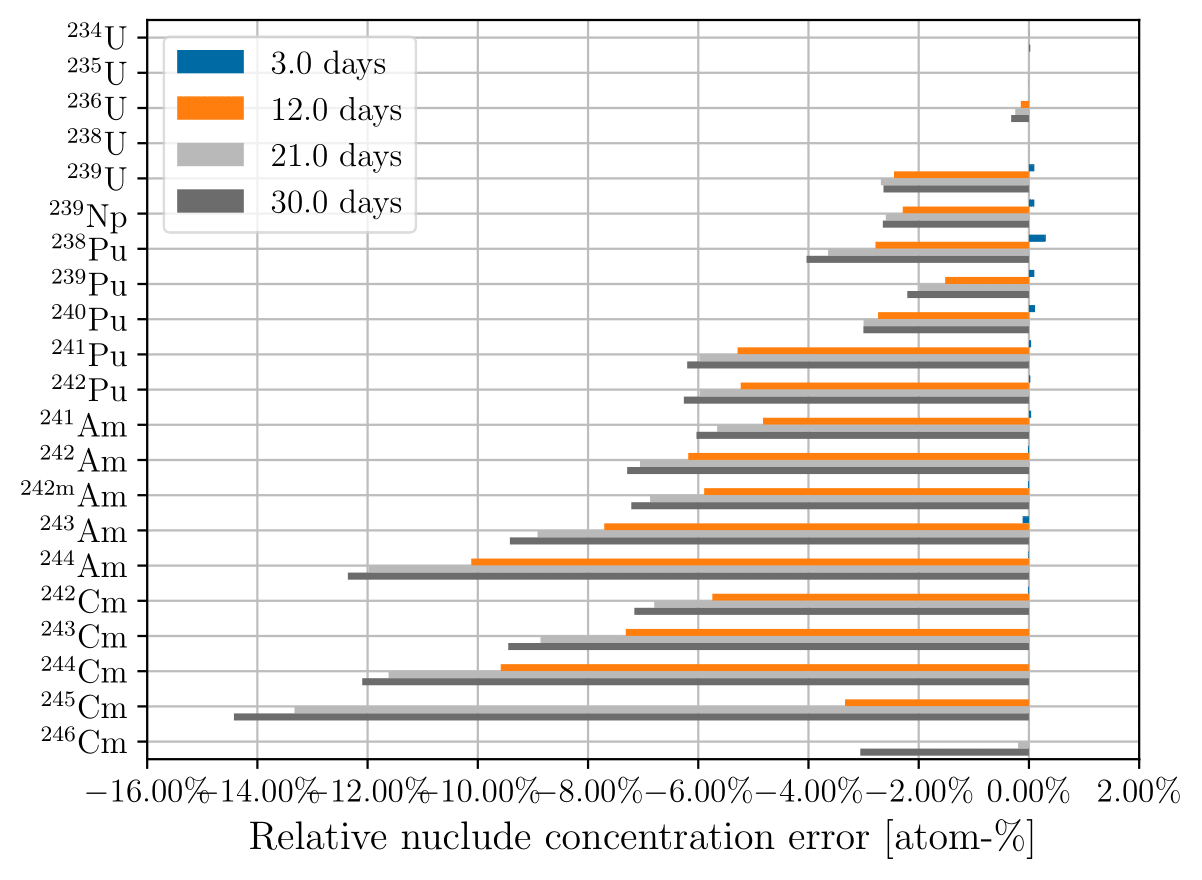

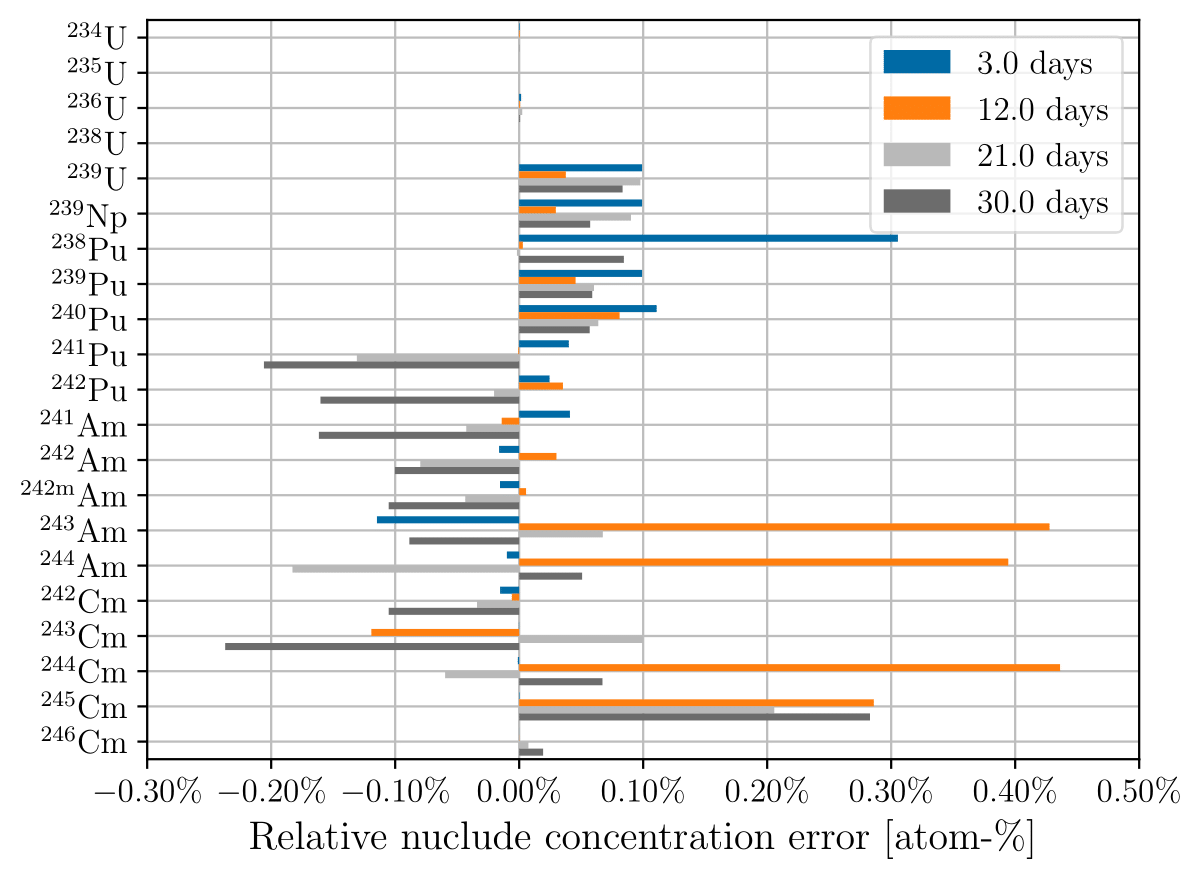

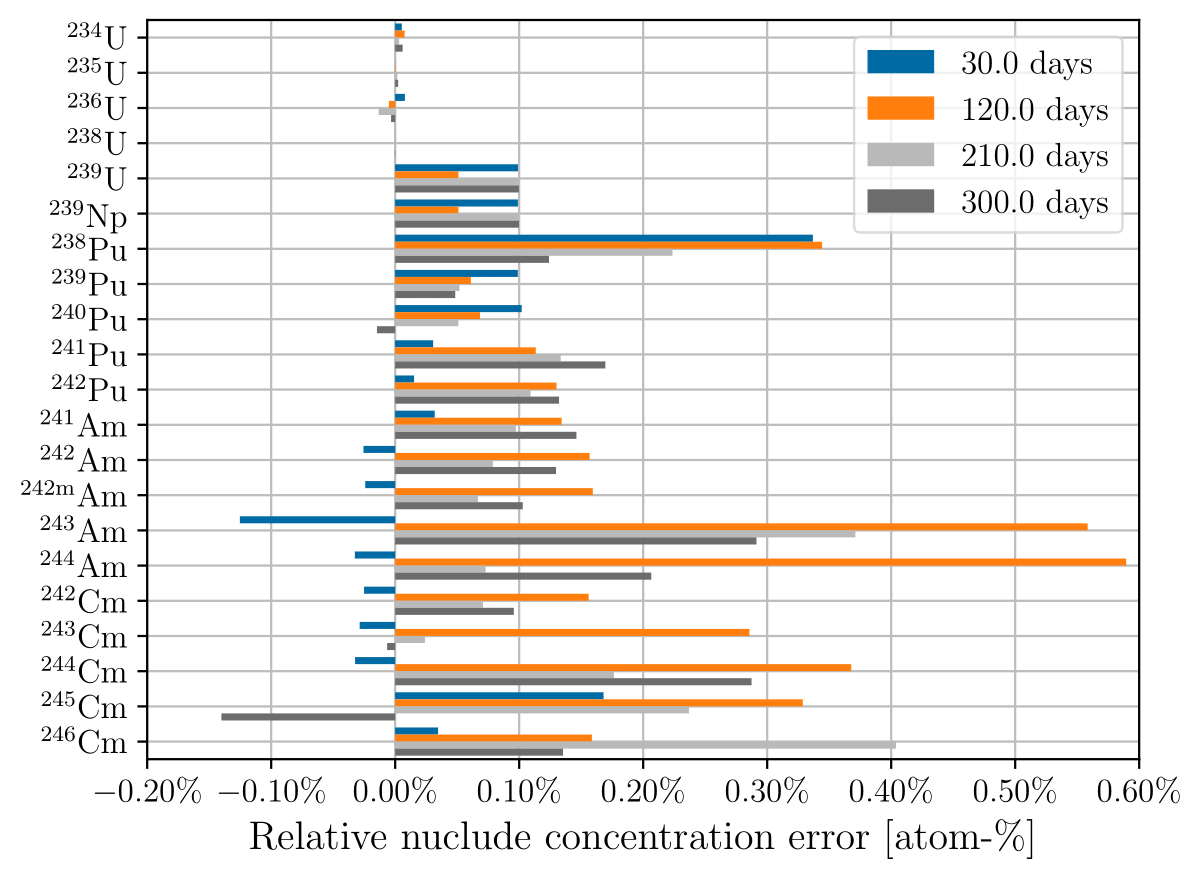

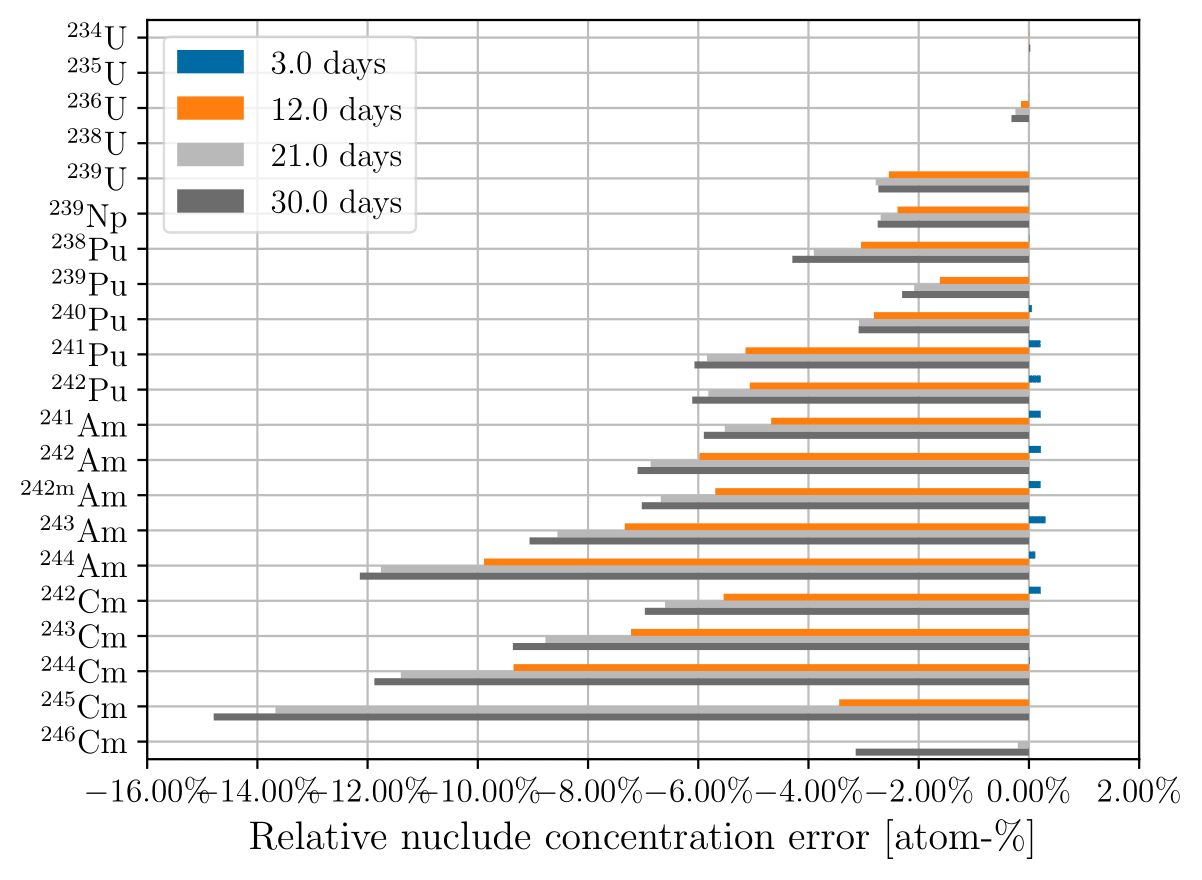

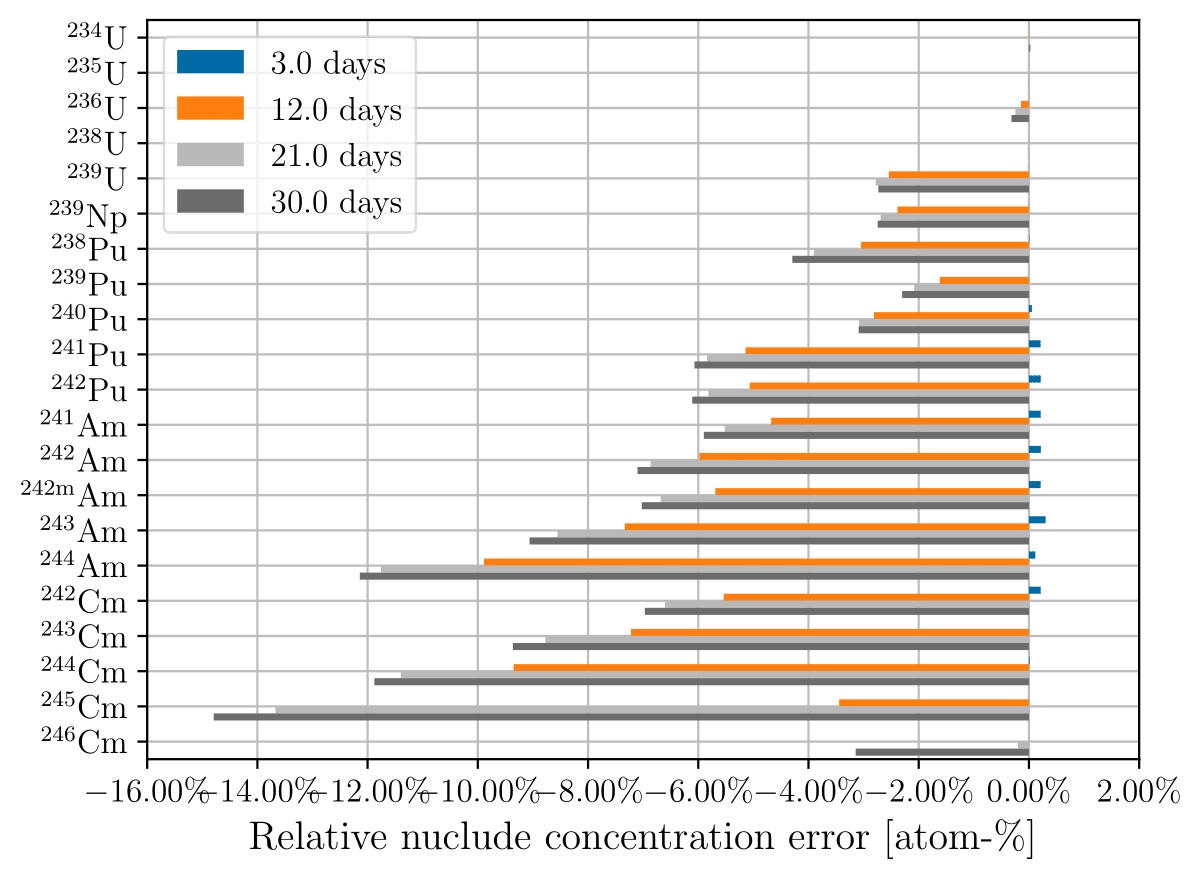

Figure 1:Relative actinide concentration error using 3-day time steps at 3, 12, 21, and 30 days of depletion for (a) constant cross sections; (b) updating cross sections.

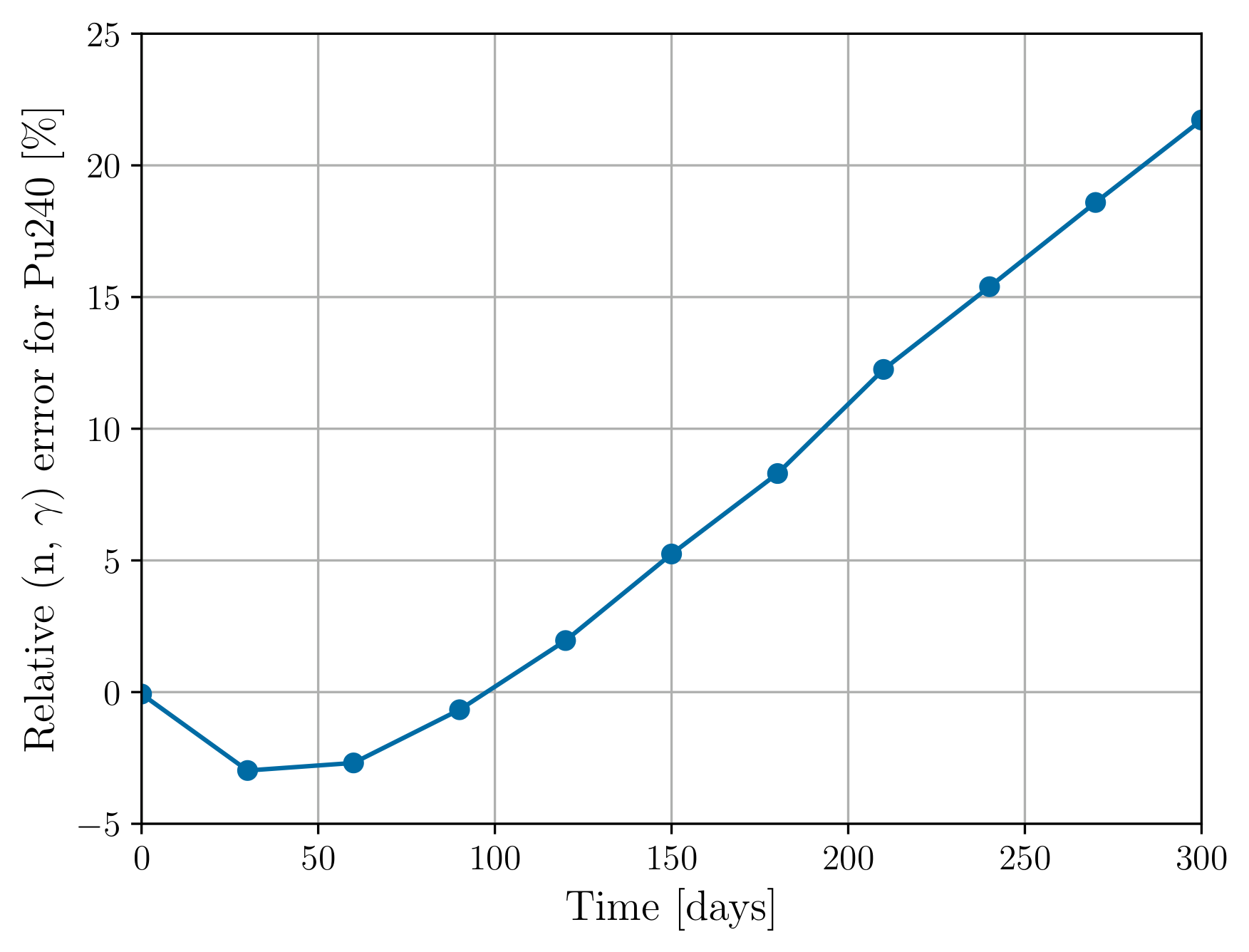

Figure 1a and Figure 1b show the relative error in predicted actinide concentration for constant cross sections and updating cross sections, respectively, using 3-day time steps. Figure 3a and Figure 3b show the same respective quantities for 30-day time steps. As expected, updating the cross sections at each depletion step results in low predicted nuclide concentration errors, on the order of a fraction of a percent. The error trend for constant cross sections depends both on the cross section and time step size. For example, constant cross sections using a 3-day time step underpredicts the Pu concentration, but at longer time steps overpredicts the concentration. Figure 2 shows the overprediction is due to overcalculating the rate of () reactions that occur on Pu.

Figure 2:Relative Pu () reaction rate error using constant cross sections and 30-day time steps.

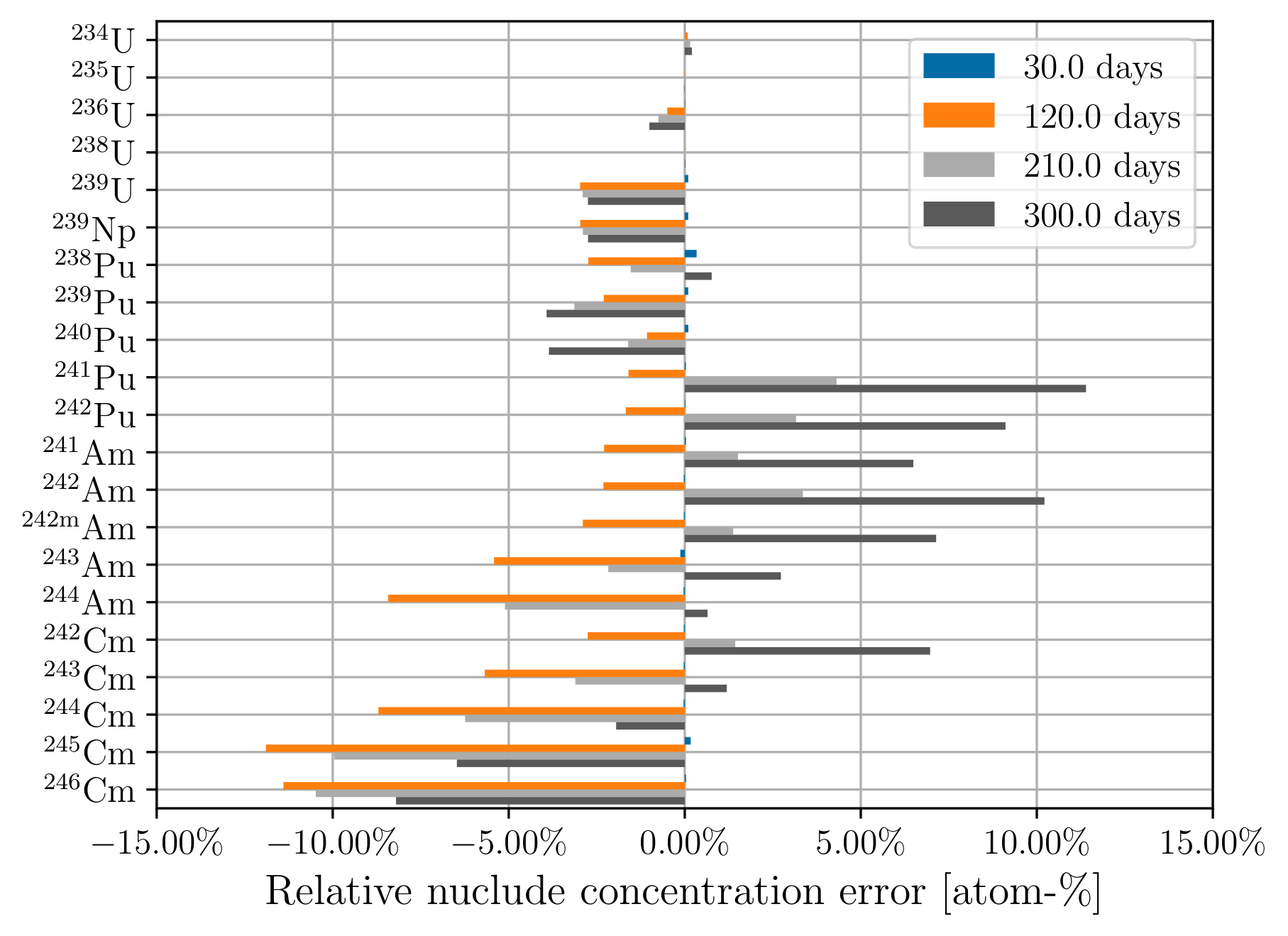

The error in Pu concentration propagates to daughter nuclides that are related to the amount of Pu, such as isotopes of Cm and Am. We observe a general trend that the less abundant nuclides have higher concentration error relative to transport-coupled depletion. The less abundant actinides have increased sensitivity to variations in production. The more abundant nuclides (U, Np, Pu, Pu) tend to have low concentration errors, (5% or less), whereas the less abundant actinides (isotopes of Am, isotopes of Cm, Pu, Pu) tend to have high (more than 10%) concentration errors depending on the nuclide of interest.

Figure 3:Relative actinide concentration error using 30-day time steps at 30, 120, 210, and 300 days of depletion for (a) constant cross sections; (b) updating cross sections.

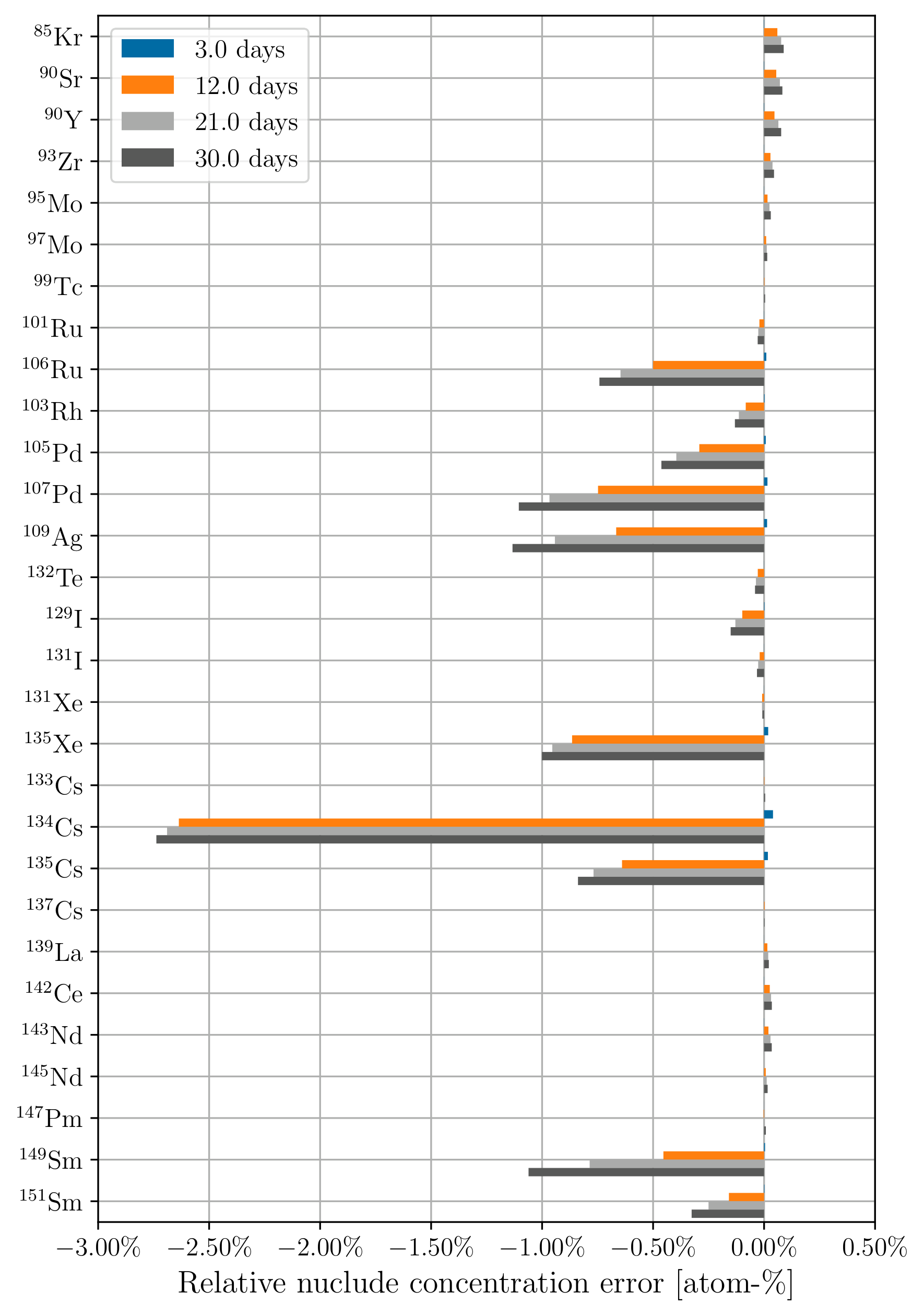

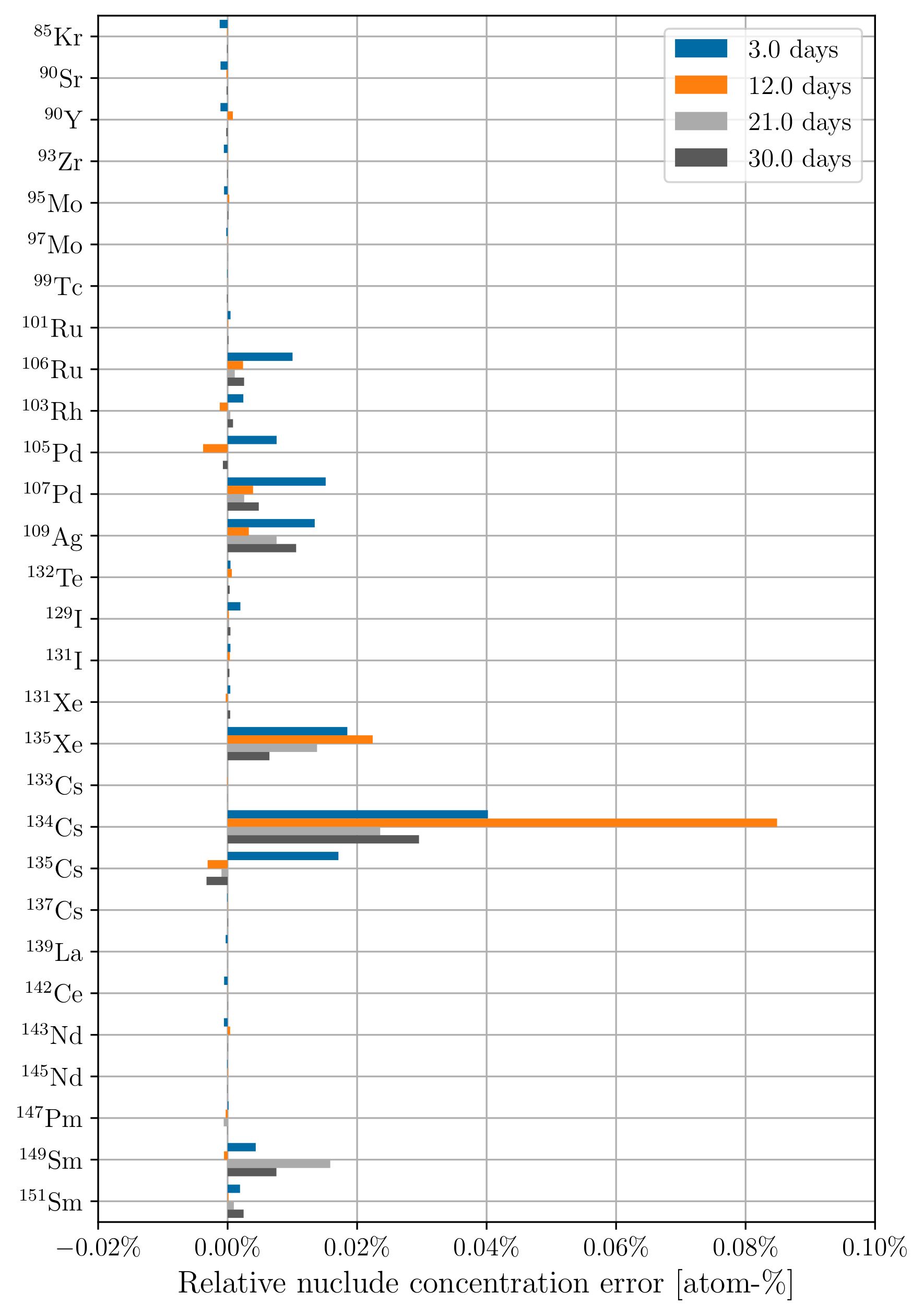

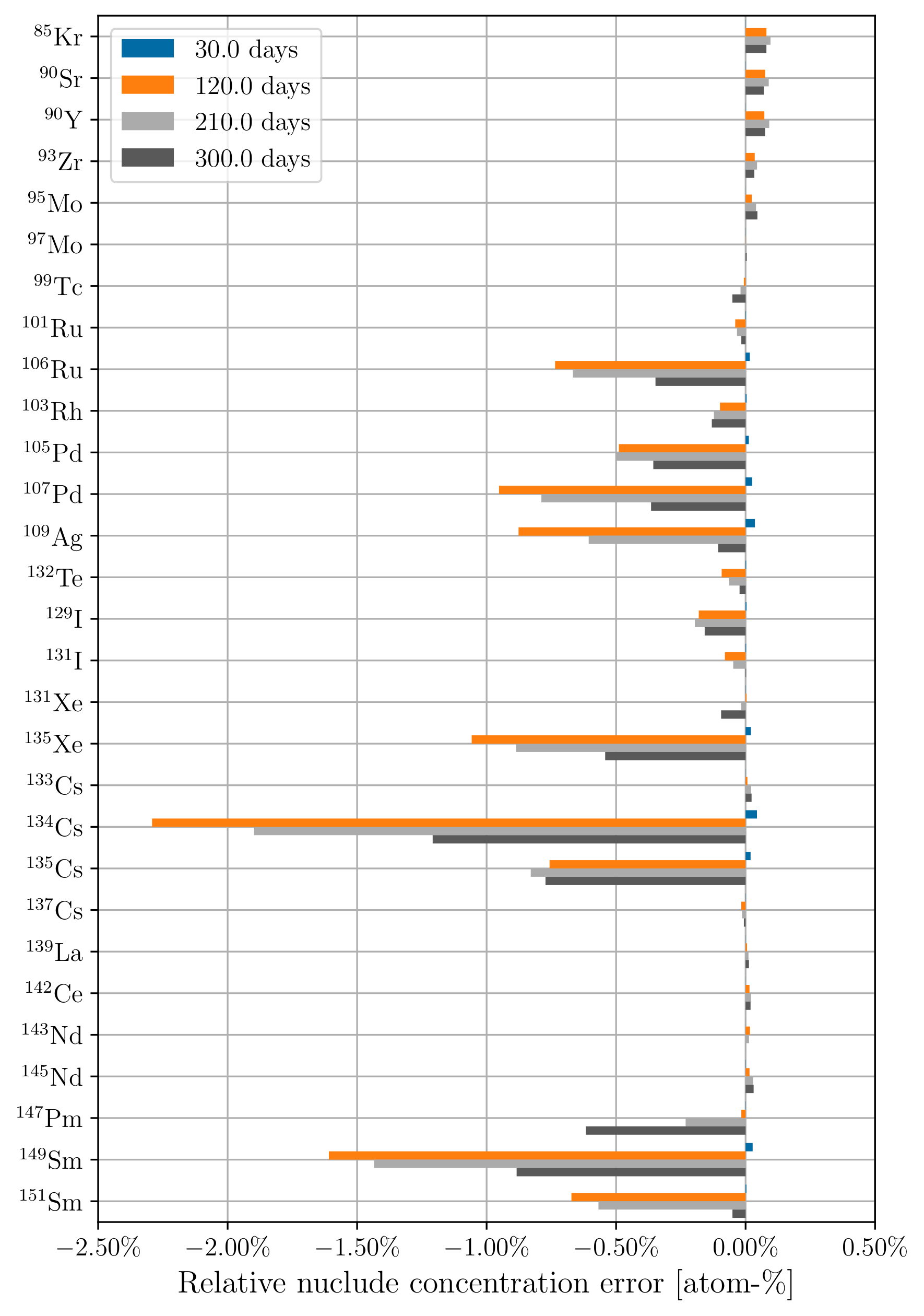

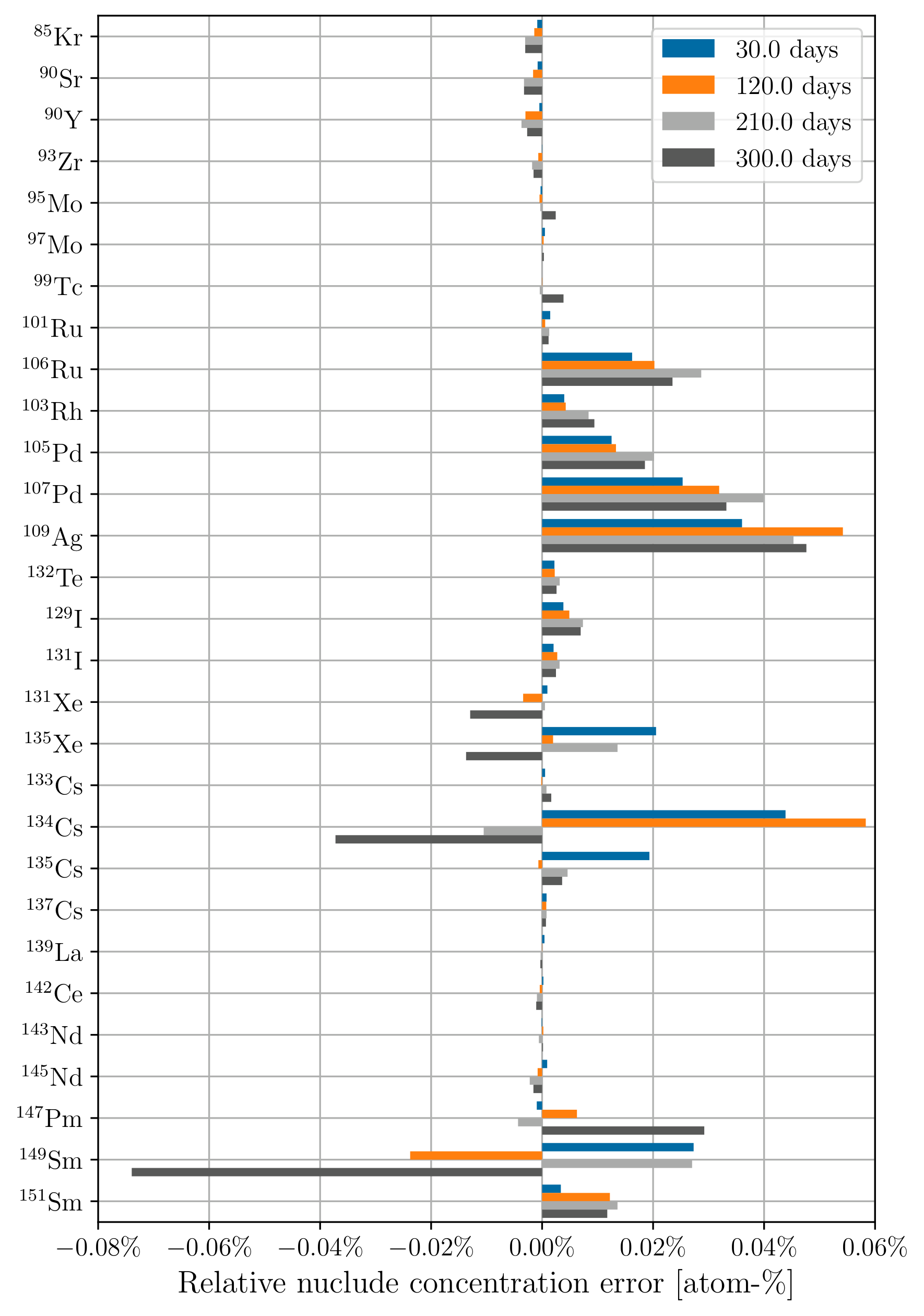

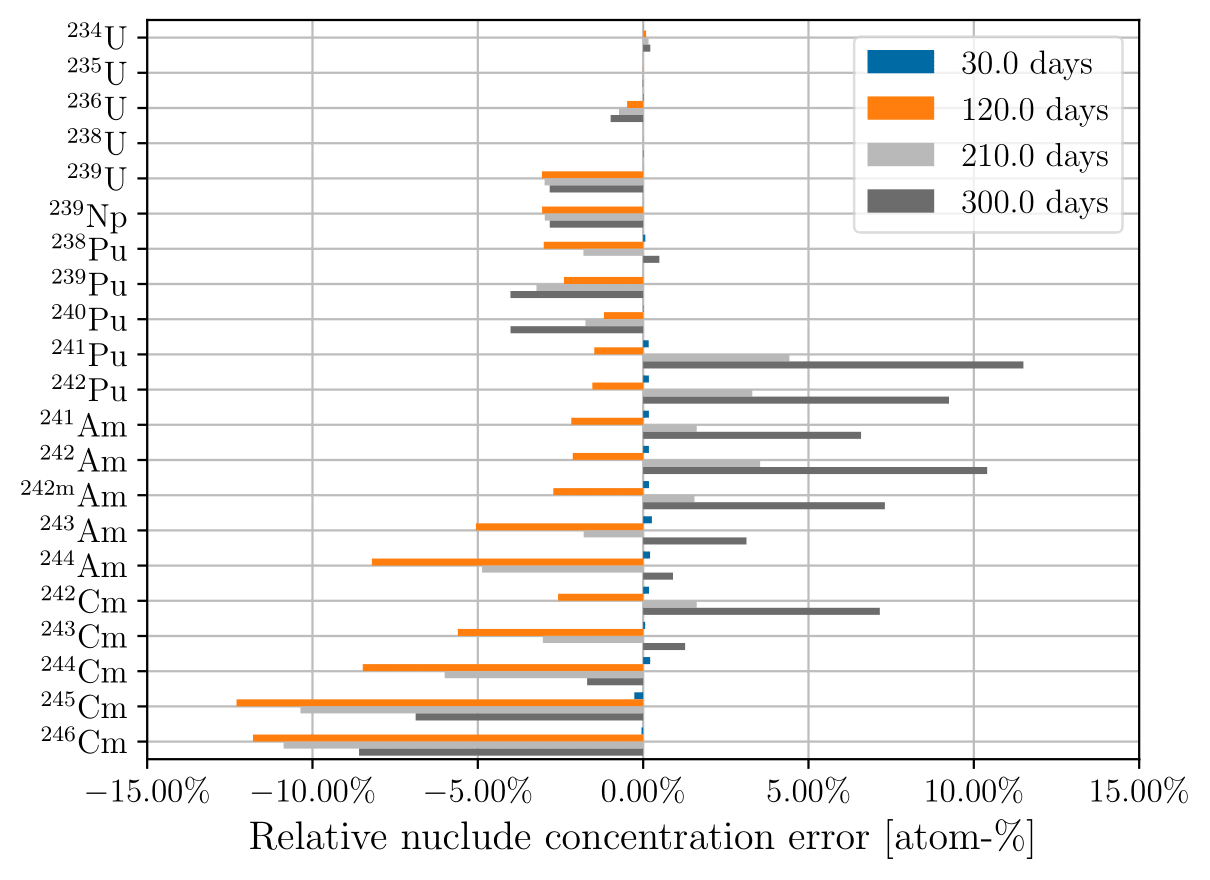

Figure 4a and Figure 4b show the relative error in predicted fission product concentration using constant cross sections and updating cross sections, respectively, using 3-day time steps. Figure 5a and Figure 5b show the same respective quantities for 30-day time steps. Similar to the actinides, updating the cross sections at each depletion step results in low predicted nuclide concentration errors. There is a lower concentration error across the board for many of these fission products compared to the actinides. This is due to the low concentration error of U, which propagates to the fission products. Other actinides with higher concentration errors are orders of magnitude less abundant in the fuel than U, so their effect on fission product concentration error is proportionally small.

Concentration errors for low-abundance nuclides using 30-day time steps follow an interesting trend where there is an initial large negative concentration error that becomes more positive over time. This behavior is due to the static cross sections and fluxes producing the same amount of these nuclides every timestep, whereas in the transport-coupled case, net production of the low-abundance nuclides decreases over time.

Figure 4:Relative fission product concentration error using 3-day time steps at 3, 12, 21, and 30 days of depletion for (a) constant cross sections; (b) updating cross sections.

Figure 5:Relative fission product concentration error using 30-day time steps at 30, 120, 210, and 300 days of depletion for (a) constant cross sections; (b) updating cross sections.

Repeating this analysis for both the CASMO-8 and CASMO-40 multi-group structures did not yield noticeable decreases in nuclide concentration errors for transport-independent depletion over the one-group case. Figure 6a and Figure 6b show the relative error in predicted actinide concentration using the CASMO-8 and CASMO-40 group structures, respectively, using 3-day time steps. Figure 7a and Figure 7b show the same respective quantities for 30-day time steps. It is possible in more complex models, like full reactor depletion, that the multi-group structure could become more important.

Figure 6:Relative actinide concentration error using constant cross sections and 3-day time steps at 3, 12, 21, and 30 days of depletion for the (a) CASMO-8 group structure; (b) CASMO-40 group structure.

Figure 7:Relative actinide concentration error using constant cross sections and 3-day time steps at 30, 120, 210, and 300 days of depletion for the (a) CASMO-8 group structure; (b) CASMO-40 group structure.

The transport-coupled simulations each took several hours to complete,

whereas the transport-independent simulations using

IndependentOperator took seconds to minutes to complete.

4Conclusion¶

In this paper, we introduced transport-independent depletion in OpenMC. This method utilized pre-computed multi-group cross sections and fluxes to calculate reaction rates for a depletion calculation. The new method is much faster than running a transport-coupled depletion simulation, albeit with a penalty to accuracy. Better accuracy will be obtained for models where the neutron flux spectrum will be constant, i.e. in fusion systems and low power fission reactors, so this new method should be used judiciously on problems where they are applicable.

This study focused exclusively on nuclide compositions. Future work may include building machinery to monitor criticality as the fuel depletes. A good starting point may be in implementing a method similar to the method to estimate used in Lovecký et al., 2014, wherein

where indicates the type of reaction, and is the neutron multiplication of reaction , defined as

In OpenMC, reactions are not used to calculate (and by extension ). In this case, in the numerator for all , and we would use an ‘effective’ absorption cross section .

Future work could focus on characterizing the effect of sub-regions on the concentration errors. The geometry used in this study is a simple PWR pincell. It is possible that the error due to static fluxes could be reduced by dividing the pincell into sub-regions to better capture radial and axial variations as is done in high-fidelity depletion of large reactor models. Another area for future work could be on studying the importance of energy group discretization for more complex reactor models. We did not find a difference in concentration errors between one-group, CASMO-8 group, and CASMO-40 group transport-independent depletion for the pincell model. It is possible that energy group discretization becomes more important for complex models with distinct depletion zones.

This work was by the Exascale Computing Project (17-SC-20-SC), a collaborative effort of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science and the National Nuclear Security Administration. This work was additionally supported through the NRC Integrated University Grant Program Fellowship.

Refactoring of the initial implementation of the MicroXS and

IndependentOperator classes to support multi-group cross sections was

supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Fusion Energy Sciences

under Award Number DE-SC0022033.

We gratefully acknowledge the computing resources provided on Bebop, a high-performance computing cluster operated by the Laboratory Computing Resource Center at Argonne National Laboratory. This research made use of the resources of the High Performance Computing Center at Idaho National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Nuclear Energy of the U.S. Department of Energy and the Nuclear Science User Facilities under Contract No. DE-AC07-05ID14517

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the following DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15103379

Copyright © 2025 Yardas et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creators.

Preliminary testing with predictor-corrector methods confirmed the higher floating point errors, however their magnitudes are marginal.

- CRAM

- Chebyshev Rational Approximation Method

- NRC

- Nuclear Regulatory Commission

- PWR

- Pressurized Water Reactor

- Romano, P. K., Hamilton, S. P., Rahaman, R. O., Novak, A., Merzari, E., Harper, S. M., Shriwise, P. C., & Evans, T. M. (2021). A Code-Agnostic Driver Application for Coupled Neutronics and Thermal-Hydraulic Simulations. Nucl. Sci. Eng., 195, 391–411. 10.1080/00295639.2020.1830620

- Merzari, E., Hamilton, S., Evans, T., Min, M., Fischer, P., Kerkemeier, S., Fang, J., Romano, P., Lan, Y.-H., Phillips, M., Biondo, E., Royston, K., Warburton, T., Chalmers, N., & Rathnayake, T. (2023). Exascale Multiphysics Nuclear Reactor Simulations for Advanced Designs. Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis. 10.1145/3581784.3627038

- Romano, P. K. (2021). Depletion capabilities in the OpenMC Monte Carlo particle transport code. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2020.107989

- Romano, P. K., Horelik, N. E., Herman, B. R., Nelson, A. G., Forget, B., & Smith, K. (2015). OpenMC: A state-of-the-art Monte Carlo code for research and development. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 82(Supplement C), 90–97. 10.1016/j.anucene.2014.07.048

- Huff, K. D., Gidden, M. J., Carlsen, R. W., Flanagan, R. R., McGarry, M. B., Opotowsky, A. C., Schneider, E. A., Scopatz, A. M., & Wilson, P. P. H. (2016). Fundamental concepts in the Cyclus nuclear fuel cycle simulation framework. Advances in Engineering Software, 94, 46–59. 10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.014

- Bachmann, A. M., Yardas, O., & Munk, M. (2024). An Open-Source Coupling for Depletion During Fuel Cycle Modeling. Nuclear Science and Engineering, 0(0), 1–14. 10.1080/00295639.2024.2393940

- Sublet, J.-C., Eastwood, J. W., Morgan, J. G., Gilbert, M. R., Fleming, M., & Arter, W. (2017). FISPACT-II: An Advanced Simulation System for Activation, Transmutation and Material Modelling. Nucl. Data Sheets, 139, 77–137. 10.1016/j.nds.2017.01.002

- Eade, T., Colling, B., Naish, J., Packer, L. W., & Valentine, A. (2020). Shutdown dose rate benchmarking using modern particle transport codes. Nucl. Fusion, 60(5), 056024. 10.1088/1741-4326/ab8181

- Peterson, E. E., Romano, P. K., Shriwise, P. C., & Myers, P. A. (2024). Development and validation of fully open-source R2S shutdown dose rate capabilities in OpenMC. Nucl. Fusion, 64, 056011. 10.1088/1741-4326/ad32dd

- Lovecký, M., Piterka, L., Prehradný, J., & Škoda, R. (2014). UWB1 – Fast nuclear fuel depletion code. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 71, 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2014.04.021