Challenges and Implementations for ML Inference in High-energy Physics

Abstract¶

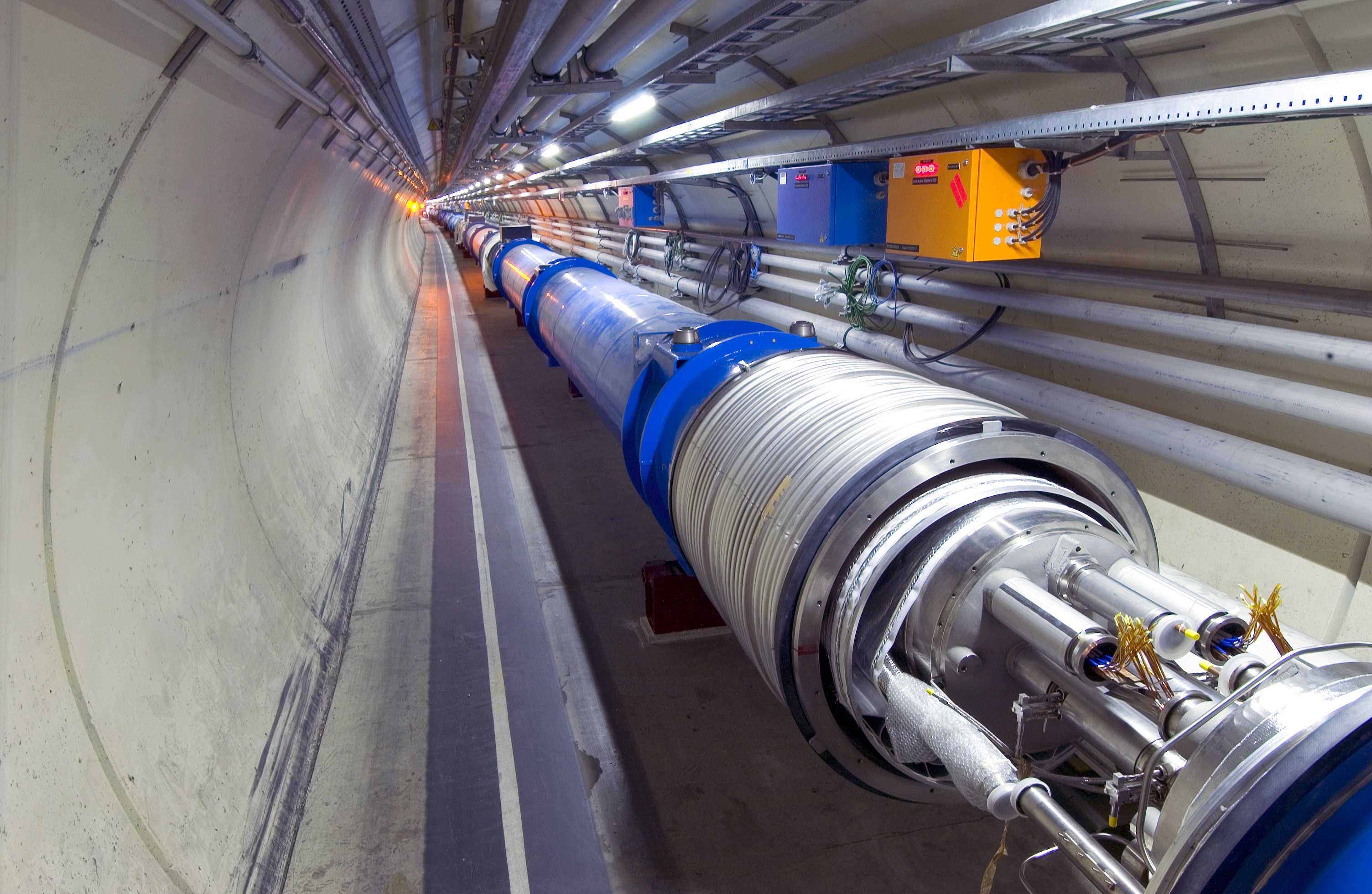

At CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, machine learning models are developed and deployed across a wide spectrum of applications, from data analysis and event reconstruction to real-time classification in trigger systems. These systems must operate with extremely high efficiency, as experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN generate enormous data streams every second, requiring rapid filtering of irrelevant events to isolate the most promising collisions. With the upcoming High-Luminosity phase of the LHC, collision rates, and therefore data volumes, will increase dramatically, placing even greater demands on the design, optimization, and deployment of machine learning models for fast and reliable inference.

This paper surveys the diverse approaches to machine learning inference currently adopted and under development at CERN to meet these challenges. We highlight methods employed by the four major LHC experiments, as well as complementary tools and frameworks designed for high-throughput environments. Particular focus is given to the unique challenges of running ML models in production at CERN, such as latency constraints, hardware optimization, and integration with large-scale computing infrastructure, and the solutions being pursued to ensure robust performance for present operations and future upgrades of the collider.

1Introduction¶

Machine learning inference is the process of applying a trained model to new data in order to generate predictions. In high-energy physics (HEP), efficient inference is essential for large-scale production workflows, where billions of collision events must be processed rapidly and accurately. Unlike many other domains, HEP workflows are deeply integrated into C++-based software frameworks, which form the backbone of event reconstruction, simulation, and data analysis. As a result, seamless integration of ML inference into C++ environments is crucial to ensure compatibility, performance, and maintainability within existing large-scale computing infrastructures.

In addition, effective thread management is vital for exploiting ML models in multi-threaded settings, ensuring scalability and optimal performance in massive data-processing pipelines. In many HEP applications, inference must be performed at the event level (for instance, classifying particle collision events in real time at the LHC trigger system), often in single-batch mode, while still meeting strict requirements on both computational speed and memory efficiency. Addressing these challenges is therefore central to enabling fast, reliable, and resource-efficient ML inference within complex scientific workflows.

2Background¶

2.1Machine Learning for High-energy Physics¶

Machine learning has become a central component of HEP research, where experiments generate petabytes of complex and noisy data each year Clarke et al., 2016. In this domain, ML provides powerful tools to address the challenges of scale, dimensionality, and heterogeneity inherent to detector data. A key application lies in signal-versus-background discrimination Vidal et al., 2021, where supervised learning algorithms are trained to identify rare events of interest, such as potential new particles or exotic decay channels against overwhelming amounts of Standard Model background processes. Beyond classification, ML is also used for particle identification Karwowska et al., 2023 and track reconstruction Baranov et al., 2019, enabling physicists to infer particle properties from detector signals with greater accuracy.

Another crucial area is trigger systems, which must make real-time decisions on whether to record an event in less than a millisecond. Here, ML models are increasingly deployed on specialized hardware (e.g., FPGAs, GPUs) Coccaro et al., 2023 to optimize triggers by rapidly distinguishing potentially interesting collisions from noise. ML also plays a major role in fast simulation and generative modeling Kita et al., 2024, where deep generative networks replicate computationally expensive detector simulations, drastically reducing computation times while preserving fidelity. In parallel, unsupervised and anomaly detection methods Fraser, 2023 are being explored to uncover unexpected patterns in data, providing model-independent avenues to search for physics beyond the Standard Model. At a broader scale, ML contributes to detector calibration, uncertainty estimation, and data compression, improving resource efficiency and the reliability of physics results.

Despite the success of widely adopted frameworks such as TensorFlow Abadi et al., 2015 and PyTorch Paszke et al., 2019, deploying ML inference in C++ based HEP environments presents unique challenges. These frameworks are primarily designed around their native Python ecosystems and model formats, limiting flexibility when integrating externally trained models. Using TensorFlow in a C++ environment is challenging, introduces heavy dependencies, and provides limited control over thread management, making deployment complex for use cases like single-event evaluation that require extremely fast, one-at-a-time processing of individual collision events, as is common in HEP workflows. PyTorch offers LibTorch, a C++ interface that is more lightweight and easier to integrate. However, extensions such as PyTorch Geometric are not supported in libtorch, as they rely on Python-heavy APIs and do not provide native C++ bindings. These constraints underscore the need for lightweight, high-performance inference solutions that integrate seamlessly into C++ based pipelines while maintaining both flexibility and efficiency.

2.2High-Luminosity LHC¶

The High-Luminosity Large Hadron Collider (HL-LHC) Apollinari et al., 2015 is the major upgrade of the LHC at CERN, planned to begin operation in the mid-2030s, with the goal of increasing the collider’s integrated luminosity by an order of magnitude compared to its predecessor. This dramatic boost in collision rates will allow physicists to probe rare processes with unprecedented precision, improve measurements of the Higgs boson, and enhance sensitivity to potential new physics. However, the HL-LHC will also introduce significant challenges: detectors must handle higher particle densities, event pileup will reach up to 200 simultaneous interactions per bunch crossing, and data volumes will grow to exabyte scales. These requirements demand innovations in data processing, triggering, reconstruction, and storage. Machine learning will play a critical role in meeting these challenges, from enabling ultra-fast, resource-efficient trigger decisions on specialized hardware, to improving event reconstruction in high-pileup environments, accelerating detector simulations, and guiding anomaly detection for unexpected signatures. By combining physics insight with advanced ML methods, the HL-LHC program will ensure that researchers can fully exploit the collider’s enhanced discovery potential.

2.3Next-Generation Triggers Project¶

An important step toward addressing the challenges of HL-LHC is the Next-Generation Triggers (NGT) project Next-Generation Triggers Project, 2023, a CERN-wide initiative that aims to prepare the LHC experiments for the unprecedented data rates expected in the HL-LHC era. With collisions producing up to 100 terabytes of raw data per second, traditional approaches to triggering and data reduction are insufficient. The NGT project brings together researchers across experiments and the CERN Theory Department to co-develop software and hardware strategies for real-time data processing. A central focus of NGT is the integration of machine learning inference into trigger systems in a way that is both scalable and low-latency. To achieve this, the project emphasizes the design of efficient interfaces that minimize data movement between detector front-ends, memory, and accelerators, as well as the development of portable solutions that can run seamlessly across heterogeneous architectures (CPUs, GPUs, FPGAs, and potentially AI-specific hardware).

3Machine Learning Inference at the Experiments¶

3.1ATLAS¶

ATLAS (A Toroidal LHC ApparatuS) is one of the two general-purpose detectors at the LHC The ATLAS Collaboration et al., 2008, designed to study a wide range of collision events, including proton–proton and nucleus–nucleus interactions. Alongside CMS, ATLAS played a leading role in the 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson. Like the other LHC experiments, ATLAS faces the primary challenge of handling the immense volume of data generated during collisions. Its complex trigger system is tasked with rapidly selecting interesting events from this continuous data stream. Research within ATLAS Gonski, 2024 has shown that convolutional and recurrent neural networks may outperform traditional signal filters for estimating the energy and timing of signals in the Electromagnetic Calorimeter (ECAL)- a subdetector that measures the energy of particles, particularly electrons and photons. Advances in fast machine learning methods may also being leveraged for accurate regression of key physical quantities, leading to improved calibration of detector signals.

Machine learning may further support reconstruction algorithms, which transform raw detector signals into physics objects and phenomena, enabling higher-level analyses. Sophisticated architectures such as Transformers can be applied to study the simulated decays of particles like b-hadrons, while anomaly detection techniques are increasingly explored to isolate unexpected phenomena from well-understood backgrounds. To support these diverse applications, ATLAS employs a robust inference infrastructure to integrate trained ML models into production workflows. Its primary software framework, Athena Elmsheuser, 2023, serves as the production environment for processing collision data and is built upon Gaudi, a shared software stack used by several CERN experiments.

3.1.1ML Inference in Athena¶

Athena employs ONNXRuntime as its primary tool for machine learning inference Chou et al., 2024, running models in the ONNX (Open Neural Network eXchange) format Bai et al., 2019. ONNXRuntime is particularly suitable because it allows seamless switching between different execution providers via job configurations, offering flexibility and maintainability. In addition to ONNXRuntime, ATLAS also leverages NVIDIA Triton Inference Server Ju, 2025 to enable Inference-as-a-Service within the Athena framework. While ONNXRuntime serves as the main inference backend, scalable strategies are essential to meet the increasing demands of simulation and collision data processing, including maximizing event throughput and efficiently utilizing accelerators such as GPUs.

To address these requirements, the AthenaTriton integration allows Athena to act as a Triton client, sending inference requests to a local or remote Triton server. This approach supports both online and offline computing workflows and enables scalable deployment of ML models. Triton provides multiple backend options, including ONNXRuntime and TensorRT NVIDIA Corporation, 2024, as well as custom Python and C++ backends, ensuring broad flexibility. Performance evaluations using perf_analyzer demonstrated that throughput scaling efficiency remained above 98% as concurrent model instances increased, while GPU utilization reached ~45%. End-to-end tests with Athena clients further showed that three concurrent threads achieved a 2.4× speedup with strong scaling efficiency. Together, these results highlight AthenaTriton as a robust and maintainable solution for integrating ML inference into ATLAS workflows at scale.

3.2CMS¶

CMS (Compact Muon Solenoid) is the other general-purpose detector The CMS Collaboration et al., 2008 at the LHC. The CMS collaboration investigates a wide range of topics, from precision studies of the Standard Model to searches for extra dimensions and dark matter. Although CMS shares the same broad scientific goals as ATLAS, it differs in its technical design, particularly in the magnet system and detector configuration. CMS has been actively exploring machine learning across diverse applications Kasieczka & Vlimant, 2022, including convolutional neural networks to denoise faster Banerjee et al., 2023, lower-quality detector simulations, CNNs for identifying hadronic tau particles, and graph neural networks for particle-flow reconstruction. More recently, the ECAL has deployed autoencoder-based anomaly detection models CMS Collaboration, 2024 to enhance data quality monitoring.

Like ATLAS, CMS operates its own dedicated software framework- CMSSW The CMS Collaboration, 2025, for simulation, calibration and alignment, and reconstruction, enabling the processing and analysis of collision data by the collaboration. The primary goal of this framework and its event data model is to provide a robust environment for developing, integrating, and scaling reconstruction and analysis software, while supporting the incorporation of advanced machine learning techniques into physics workflows.

3.2.1ML Inference in CMSSW¶

For its machine learning use cases ranging from jet tagging with the graph-convolutional model ParticleNet Qu & Gouskos, 2020 to end-to-end reconstruction of particle hits into clusters using the GravNet architecture Qasim et al., 2022 with dynamic graph building, CMS employs both direct and indirect inference strategies. For direct inference, CMS primarily uses ONNXRuntime, which is straightforward to maintain and relatively tolerant of different GCC/CUDA versions. However, this approach faces limitations, particularly with graph neural networks, which are often not fully supported in ONNX. To address such cases, CMS has been exploring direct PyTorch support Valsecchi & Yao, 2025, especially for models that are difficult to export to ONNX or that require custom operations. To further integrate deep learning into HEP workflows, CMSSW supports both ahead-of-time and just-in-time compilation strategies, and recent work has investigated enabling inference on heterogeneous architectures via ALPAKA Zenker et al., 2016, connecting directly to PyTorch tensors.

For indirect inference, CMS uses the SONIC (Service for Optimized Network Inference on Coprocessors) approach Hayrapetyan et al., 2024 for Inference-as-a-Service capabilities. In this model, CPU-based CMSSW clients send inference requests to remote coprocessor servers, where a Triton Inference Server executes the models. Triton supports multiple model instances, dynamic batching, and asynchronous inference requests per ML algorithm per event, while CMSSW clients continue data processing in parallel. SONIC offers flexibility across coprocessor types (GPUs, IPUs, FPGAs) and ML backends, and even supports non-ML GPU workloads through custom Triton backends. To extend this capability to large-scale distributed environments, the SuperSONIC Chou et al., 2025 package enables Kubernetes-based deployment with load balancing, autoscaling, and rate limiting across multiple GPUs, along with observability via Prometheus, Grafana, and OpenTelemetry. Clients discover available servers through site configurations, with fallback to local CPU or GPU inference when remote resources are unavailable. Ongoing development focuses on improving robustness through retry mechanisms, expanding supported ML models, and preparing the framework for Run 3 operations and the upcoming High-Luminosity LHC era.

3.3LHCb¶

The LHCb (Large Hadron Collider beauty) experiment The LHCb Collaboration et al., 2008 is one of the two specialized collaborations at the LHC. Its primary goal is to search for indirect evidence of new physics through studies of charge–parity violation and rare decays of beauty and charm hadrons. Like other LHC experiments, LHCb relies on machine learning models for a variety of tasks, including track reconstruction using models such as the Bonsai BDT (Boosted Decision Tree) Gligorov & Williams, 2013, particle identification (e.g., electrons, muons, pions) Derkach, Denis et al., 2019 modeled as a multiclass classification problem with neural networks and XGBoost, and particle decay selection using topological triggers through MatrixNet Likhomanenko et al., 2015.

Due to LHCb’s specialized design, its detectors produce a readout of ~5 TB/s, processed via a software-based trigger system without requiring dedicated hardware triggers Veghel, 2025. The experiment employs a dual High-Level Trigger (HLT) system: HLT1 performs fast track reconstruction van Tilburg, 2005, while HLT2 executes high-fidelity reconstruction NVIDIA Corporation, 2024. ML inference is extensively online triggers and simulation frameworks, with throughput constraints guiding the choice of methods. In the GPU-based HLT1, small MLPs are executed on NVIDIA A5000 GPUs, leveraging general-purpose libraries such as ONNX Runtime and TensorRT , which provide flexibility and standardized model support, though kernel overhead can limit performance compared to custom solutions. In the CPU-based HLT2, LHCb uses custom compile-time inference tools integrated into the Gaudi framework, enabling SIMD vectorization, compile-time optimizations, and efficient weight loading. This approach achieves 2–3× speedups in reconstruction timing and supports rapid retraining and deployment via a PyTorch-based pipeline.

For simulation, fast inference libraries including the PyTorch C++ API and ONNXRuntime are integrated to support research and unify inference across the software stack. Key ML applications include ghost track rejection, particle identification, and classification of reconstructed objects from heavy-flavor decays, typically using compact MLPs with 10–20 input features. Overall, while custom compile-time inference currently dominates online workflows due to its superior speed, ongoing efforts focus on generalizing flexible inference libraries and building maintainable, high-performance, unified ML pipelines across LHCb.

3.4ALICE¶

ALICE (A Large Ion Collider Experiment) Aamodt & others, 2008 is a specialized LHC experiment designed to study the physics of strongly interacting matter at extreme energy densities, where a phase of matter called the quark-gluon plasma forms. Like other LHC experiments, ALICE employs machine learning Haake, 2018 for tasks such as particle identification, jet reconstruction, and simulations. Applications include neural networks for particle identification Derkach, Denis et al., 2019, BDTs for event selection, and clustering in the Time Projection Chamber (TPC), which is the central barrel detector used for tracking charged particles and performing particle identification.

ALICE’s ML pipeline typically involves model development in PyTorch, followed by export to the ONNX format, and inference through the ONNXRuntime’s C++ API Sonnabend, 2025. ONNXRuntime serves as the primary inference framework, leveraging both CPU and GPU resources to manage the high data rates and occupancies of Run 3. ML applications span physics analysis tasks such as TPC particle identification, jet-pT background correction, and heavy-flavor BDT triggers, as well as online workflows like GPU-based TPC clustering at 3.5 TB/s The ALICE Collaboration et al., 2010. ORT allows PyTorch models to be converted into efficient inference graphs and integrated into C++ workflows with dynamic column access for flexibility. GPU acceleration is central, with custom CUDA/ROCm stream implementations supporting multiple parallel streams per GPU, achieving orders-of-magnitude speedups compared to CPU execution. Additional developments include GAN-based fast simulations, graph networks for track matching, and generalized particle identification using multiple detectors. Despite challenges such as memory inefficiencies and multi-threaded execution issues on SLURM clusters, ALICE has built a fully functional inference framework, making ML indispensable for both online reconstruction and offline analysis in the high-rate environment of Run 3 and beyond.

4Standardized Inference Runtimes¶

Examining the machine learning requirements across the experiments and their inference workflows highlights the extensive use of tools such as ONNXRuntime and TensorRT.

4.1ONNXRuntime¶

ONNX is a standardized format for representing deep learning models, designed to facilitate interoperability between different frameworks such as TensorFlow and PyTorch. By providing a common representation, ONNX allows trained models to be exported and deployed across a variety of runtime environments and hardware platforms. However, ONNX cannot fully represent all model architectures, particularly those used in graph neural networks, which limits its applicability for certain HEP models.

To enable efficient inference of ONNX models, Microsoft developed ONNXRuntime, an open-source engine supporting both C++ and Python environments. ONNXRuntime runs on CPUs and GPUs, and it has been successfully integrated into HEP frameworks such as ATLAS and CMS. Its convenient C++ API and fine-grained thread control make it particularly valuable for production workflows. However, several challenges remain: certain ML operations are not supported by ONNXRuntime, which can prevent some models from being converted to ONNX altogether; inference values may vary slightly across runs; and ONNXRuntime does not natively support access to remote coprocessors- specialized hardware like GPUs and FPGAs, or the acceleration of non-ML algorithms on these devices. Despite these limitations, ONNX and ONNXRuntime provide a robust foundation for deploying machine learning models efficiently within C++-based scientific computing workflows, particularly when combined with complementary tools like TensorRT for GPU optimization.

4.2TensorRT¶

NVIDIA TensorRT is an inference engine ecosystem tailored for high-performance deep learning inference on NVIDIA GPUs. It includes both a runtime and a suite of model-optimization tools, such as the TensorRT-LLM library, Model Optimizer, and Cloud services, for producing highly efficient, low-latency inference engines. TensorRT accelerates neural network inference by applying a range of optimizations: it performs precision calibration to support lower-precision formats like FP16, INT8, FP8, and INT4, significantly improving throughput and reducing memory usage; layer and tensor fusion, which merges multiple operations into fewer GPU kernels; kernel auto-tuning, which selects optimal GPU kernels per hardware; and dynamic tensor memory management, which optimizes memory allocation during inference. It supports importing models from popular deep learning frameworks, such as TensorFlow, PyTorch, Caffe, MXNet, or through ONNX formats, offering both C++ and Python APIs for integration and optimization. TensorRT achieves up to 36× faster inference compared to CPU-only baselines and even up to 40× higher throughput with sub-7 ms latency in real-time use cases such as embedded systems and data centers.

5HEP-developed Inference Frameworks¶

5.1SOFIE¶

To address the challenges of efficient machine learning inference in C++ environments, the ML4EP team at CERN have been developing SOFIE (System for Optimized Fast Inference code Emit) An et al., 2023, a tool within ROOT/TMVA Albertsson et al., 2020 designed to generate optimized C++ code from trained ML models. SOFIE is capable of converting models in ONNX format to its own Intermediate Representation. Additionally, it provides support to parse TensorFlow/Keras and PyTorch models, as well as message-passing Graph Neural Networks from DeepMind’s Graph Nets library Battaglia et al., 2018. The key advantage of SOFIE is its ability to produce standalone C++ code that can be directly invoked within C++ applications with minimal dependencies, requiring only Basic Linear Algebra Subroutines (BLAS) for numerical computations. This makes integration seamless for high-energy physics workflows and other computationally demanding applications. Moreover, the generated code can be compiled at runtime using ROOT Brun & Rademakers, 1997 Canal et al., 2025 Cling Just-In-Time compilation, allowing for flexible execution, including within Python environments. By eliminating the need for heavyweight machine learning frameworks during inference, SOFIE offers a highly efficient and easily deployable solution for ML model evaluation. While initially SOFIE struggled for more complex models, thereby taking more time and memory during inference as mentioned in Moneta et al., 2024, several optimizations have recently been applied to accelerate their process. These optimizations Sengupta et al., 2025 include efficient reuse of intermediate memory, fusing multiple operators in the model graph, node eliminations, etc. Recent benchmarking suggests SOFIE to be

5.2hls4ml¶

hls4ml (High-level synthesis for Machine Learning) Duarte & others, 2018 is an open-source software–hardware codesign workflow designed to make machine learning implementations on energy-efficient hardware accessible to domain scientists. It translates trained neural networks from common ML frameworks such as TensorFlow, PyTorch, and QKeras into digital hardware implementations using high-level synthesis (HLS) for FPGAs and ASICs. By supporting techniques like quantization-aware training (where networks are trained while simulating reduced numerical precision, improving robustness to low-bit representations), pruning, and tunable parallelization, hls4ml enables the creation of low-latency and low-power ML accelerators optimized for specific scientific applications. The framework provides Python APIs, visualization tools, and bit-accurate emulation (a software execution mode that reproduces the exact fixed-point arithmetic of the target hardware), helping non-experts explore trade-offs in latency, throughput, power, and resource usage. Initially developed for real-time, low-latency tasks in high-energy physics, hls4ml has expanded to broader low-power applications, offering end-to-end workflows for both FPGA and ASIC backends, and significantly reducing the design cycle.

5.3PQuant¶

PQuant Niemi et al., 2025 is a tool designed for end-to-end hardware-aware model compression, aimed at training and optimizing compressed neural networks for deployment under strict hardware constraints. It automates model wrapping, training, and cleanup, requiring no deep knowledge of compression techniques from the user. The library supports pruning and quantization of weights and biases, with hyperparameters fully configurable through a simple config file. Users can enable or disable pruning and quantization, choose pruning methods, and specify quantization parameters such as bit-width (default or layer-specific), symmetric or asymmetric quantization, and optional hard quantization for certain activations. Training is organized into distinct phases: pretraining, training, and fine-tuning managed by a generic training function where users only need to provide training and validation functions. PQuant allows fine-grained control, such as disabling pruning for specific layers or using different quantization strategies across layers, and it supports iterative training with weight rewinding. Results on models like SmartPixels and ResNet20 demonstrate its ability to significantly reduce parameters while maintaining accuracy. Future developments include TensorFlow support, integration with hls4ml, and automated hyperparameter optimization.

5.4Conifer¶

Conifer Summers, 2024 is a framework designed to map decision forests onto FPGA firmware, enabling extremely low-latency and high-throughput inference. Decision forests, which are ensembles of decision trees, remain valuable for machine learning in edge and resource-constrained environments because they are lightweight, robust, and fast. Conifer integrates with popular training tools and translates trained models into FPGA implementations, exploiting parallelism and pipelining to minimize latency. It supports both HLS and VHDL (Very High-Speed Integrated Circuit Hardware Description Language) backends, with latencies in the 10–100 ns range depending on depth and number of trees. Applications already demonstrated include medical image segmentation on embedded devices, real-time filtering in tracking detectors, and particle reconstruction in high-energy physics experiments. To address the challenge of model reconfiguration without lengthy synthesis cycles, Conifer also introduces the Forest Processing Unit (FPU), a dynamic architecture where boosted decision tree models are represented as data and efficiently evaluated across parallel tree engines. This makes Conifer a practical tool for scenarios requiring real-time predictive performance in scientific and embedded systems.

6Conclusion¶

Machine learning inference has become a central component of data processing in CERN’s experiments. As this survey has outlined, the challenges of scale, latency, and heterogeneous architectures are being tackled through a range of solutions, from widely used standardized runtimes such as ONNXRuntime and TensorRT to experiment-specific strategies embedded within their major software frameworks. While each experiment has developed inference pipelines adapted to its detector design and computing environment, they share common requirements: seamless integration with C++ based workflows, efficient use of heterogeneous hardware, and robustness under extreme data rates.

Looking ahead to the High-Luminosity LHC era, these requirements will only grow more demanding, with increasing event complexity and data volumes. Alongside established runtimes, a number of research and development efforts, such as SOFIE- which generates optimized standalone C++ code for model inference, and hls4ml, for FPGA-based acceleration are being explored for improved performance and hardware efficiency.

Overall, the developments surveyed here demonstrate how machine learning inference has become very important in high-energy physics. These efforts for scalable and efficient inference pipelines will be essential to the upcoming physics research of the HL-LHC and future experiments.

This work has been funded by the Eric & Wendy Schmidt Fund for Strategic Innovation through the CERN Next Generation Triggers project under grant agreement number SIF-2023-004.

Copyright © 2025 Sengupta & Moneta. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creators.

- ASIC

- Application-specific Integrated Circuit

- ATLAS

- A Toroidal LHC ApparatuS

- CERN

- European Organization for Nuclear Research

- CMS

- Compact Muon Solenoid

- CMSSW

- CMS Software Framework

- FPGA

- Field-Programmable Gate Array

- GPU

- Graphics Processing Unit

- HEP

- High-Energy Physics

- HL-LHC

- High-Luminosity LHC

- HLS

- High-Level Synthesis

- hls4ml

- High-level Synthesis for Machine learning

- LHC

- Large Hadron Collider

- ML

- machine learning

- ONNX

- Open Neural Network eXchange

- SOFIE

- System for Optimized Fast Inference code Emit

- SONIC

- Service for Optimized Network Inference on Coprocessors

- TMVA

- Toolkit for Multi-Variate Analysis

- Clarke, P., Coveney, P. V., Heavens, A. F., Jäykkä, J., Joachimi, B., Karastergiou, A., Konstantinidis, N., Korn, A., Mann, R. G., McEwen, J. D., de Ridder, S., Roberts, S., Scanlon, T., Shellard, E. P. S., & Yates, J. A. (2016). Big data in the physical sciences: challenges and opportunities. ATI Scoping Report.

- Vidal, X., Dieste, L., & Suárez, Á. (2021). How to Use Machine Learning to Improve the Discrimination between Signal and Background at Particle Colliders. Applied Sciences, 11, 11076. 10.3390/app112211076

- Karwowska, M., Jakubowska, M., Graczykowski, Ł., Deja, K., & Kasak, M. (2023). Particle identification with machine learning in ALICE Run 3. 10.48550/arXiv.2309.07768

- Baranov, D., Mitsyn, S., Goncharov, P., & Ososkov, G. (2019). The Particle Track Reconstruction based on deep Neural networks. EPJ Web of Conferences, 214, 06018. 10.1051/epjconf/201921406018

- Coccaro, A., Armando Di Bello, F., Giagu, S., Rambelli, L., & Stocchetti, N. (2023). Fast neural network inference on FPGAs for triggering on long-lived particles at colliders. Machine Learning: Science and Technology, 4(4), 045040. 10.1088/2632-2153/ad087a

- Kita, M., Dubiński, J., Rokita, P., & Deja, K. (2024). Generative Diffusion Models for Fast Simulations of Particle Collisions at CERN. 10.48550/arXiv.2406.03233

- Fraser, K. M. (2023). Anomaly Detection in Particle Physics. Presentation at the 11th Large Hadron Collider Physics (LHCP) Conference 2023. https://indico.cern.ch/event/1198609/contributions/5366508/attachments/2653550/4595418/Fraser_LHCP_2023_Talk.pdf

- Abadi, M., Agarwal, A., Barham, P., Brevdo, E., Chen, Z., Citro, C., Corrado, G. S., Davis, A., Dean, J., Devin, M., Ghemawat, S., Goodfellow, I., Harp, A., Irving, G., Isard, M., Jia, Y., Jozefowicz, R., Kaiser, L., Kudlur, M., … Zheng, X. (2015). TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Systems. https://www.tensorflow.org/

- Paszke, A., Gross, S., Massa, F., Lerer, A., Bradbury, J., Chanan, G., Killeen, T., Lin, Z., Gimelshein, N., Antiga, L., Desmaison, A., Köpf, A., Yang, E., DeVito, Z., Raison, M., Tejani, A., Chilamkurthy, S., Steiner, B., Fang, L., … Chintala, S. (2019). PyTorch: an imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates Inc. 10.48550/arXiv.1912.01703

- Apollinari, G., Brüning, O., Nakamoto, T., & Rossi, L. (2015). High Luminosity Large Hadron Collider HL-LHC. CERN. 10.5170/CERN-2015-005.1

- Next-Generation Triggers Project. (2023). Next Generation Triggers - Public proposal. Next Generation Triggers. 10.17181/nke6y-e3957

- The ATLAS Collaboration, Aad, G., Abat, E., Abdallah, J., Abdelalim, A. A., Abdesselam, A., Abdinov, O., Abi, B. A., Abolins, M., Abramowicz, H., Acerbi, E., Acharya, B. S., Achenbach, R., Ackers, M., Adams, D. L., Adamyan, F., Addy, T. N., Aderholz, M., Adorisio, C., … Zychacek, V. (2008). The ATLAS Experiment at the CERN Large Hadron Collider. Journal of Instrumentation, 3(08), S08003. 10.1088/1748-0221/3/08/S08003

- Gonski, J. (2024). Learning by machines, for machines: Artificial Intelligence in the world’s largest particle detector. CERN. https://atlas.cern/Updates/Feature/Machine-Learning

- Elmsheuser, J. (2023). ATLAS ATHENA Configuration. Presentation at the ePIC Software & Computing Weekly Meeting 2023. https://indico.bnl.gov/event/20123/contributions/78799/attachments/48664/82783/c_190723.pdf

- Chou, Y.-T., Stanislaus, B., Leggett, C., Zhao, H., Esseiva, J., Calafiura, P., Hsu, S.-C., Tsulaia, V., & Ju, X. (2024). AthenaTriton: A Tool for running Machine Learning Inference as a Service in Athena. Presentation at the 27th Conference on Computing in High Energy and Nuclear Physics 2024. https://indico.cern.ch/event/1338689/contributions/6010068/