OptiMask: Efficiently Finding the Largest NaN-Free Submatrix

Abstract¶

When working with tabular data, many processes cannot handle missing values. While imputation strategies are commonly used, another approach is to extract a NaN-free submatrix. Simply dropping every row or column containing NaN values can drastically reduce the dataset, potentially leaving no usable data. OptiMask is a heuristic designed to solve the following optimization problem: identifying the submatrix of maximum size (in terms of the number of elements) without missing values. This submatrix is composed of rows and columns that are not necessarily contiguous in the original data. OptiMask determines the sets of rows and columns to remove from the input matrix, providing either an exact or near-optimal submatrix.

1Introduction¶

Missing data is a common challenge in data analysis, often represented as NaN (Not a Number) values in matrices or DataFrames. Many algorithms and statistical methods require complete datasets, necessitating effective handling of missing values Little & Rubin, 2019Rubin, 2004. Traditional approaches include imputation (replacing missing values with estimates) and complete-case analysis (discarding rows/columns with any NaN) Schafer, 1997Van Buuren, 2018. However, imputation can introduce bias White et al., 2011, while complete-case analysis may discard excessive data, especially when missing values are evenly distributed Enders, 2010.

An alternative strategy is to identify the largest possible NaN-free submatrix, while preserving as much of the original, unaltered data as possible. This reduces to an optimization task: remove the minimal set of rows and columns to yield a NaN-free submatrix of maximum size.

This problem is computationally challenging, as the search space grows exponentially with the number of rows and columns containing NaN. Exact solutions (e.g., linear programming) guarantee optimality but are prohibitively expensive for large matrices.

Heuristic methods like OptiMask provide near-optimal solutions efficiently.

OptiMask iteratively permutes rows and columns to isolate NaN values along a frontier, simplifying the search for the largest contiguous NaN-free submatrix.

By combining randomization with multiple restarts, it reliably finds high-quality solutions.

This paper explores the OptiMask algorithm, theoretical foundations, and practical performance across diverse datasets, including large and structured matrices. It also discusses the optimask Python package (https://

2Problem Formalization and Challenges¶

2.1Mathematical Definition¶

Given an matrix with missing values (NaN), the goal is to find:

A subset of rows and columns such that the submatrix contains no NaN values.

The solution maximizing the size of the submatrix.

2.2The Fundamental Trade-off¶

When handling missing values in a matrix, we must decide whether to remove affected rows, columns, or a combination of both. The optimal choice depends on the matrix’s dimensions and the distribution of NaN values:

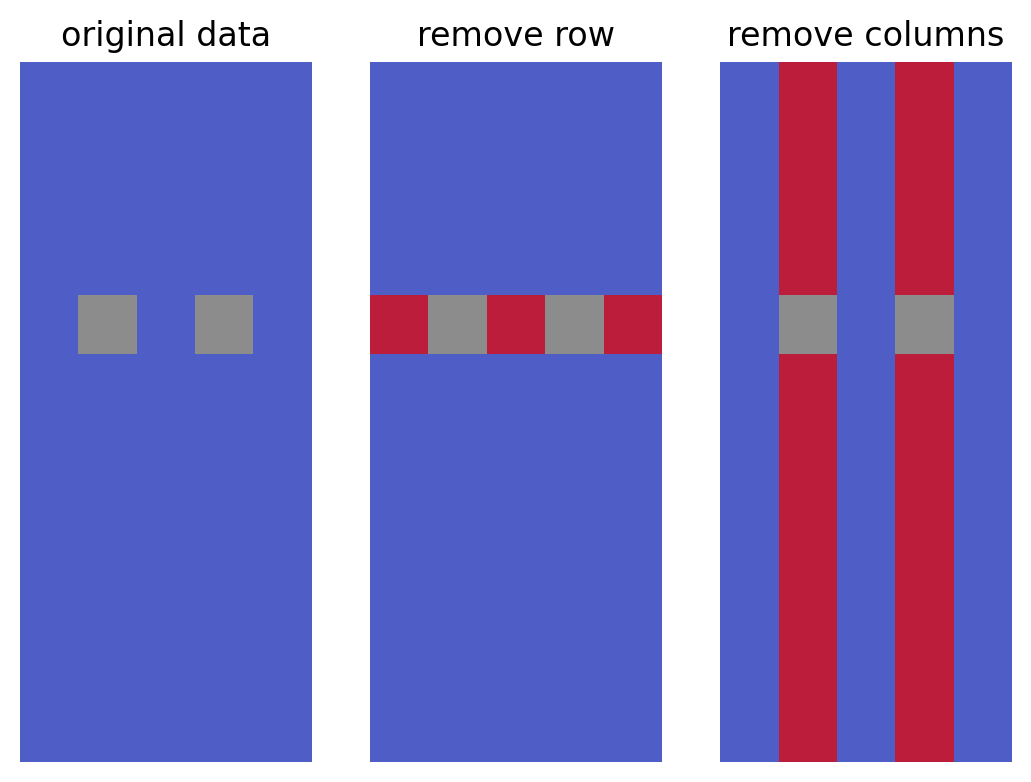

Toy Example:

In tall matrices (rows > columns), removing a problematic row typically preserves more data.

In wide matrices (columns > rows), removing an affected column is usually preferable.

In this toy example, removing the row with the two NaNs yields a larger submatrix (11x5) than removing the two columns, which results in a smaller submatrix (12x3) from the original 12x5 matrix.

Generalizing the Intuition: The toy example suggests a greedy heuristic:

If a row contains many NaNs, removing that single row may be better than removing all corresponding columns (which could discard more data).

Conversely, if a column contains many NaNs, removing it might be better than eliminating all affected rows.

Complex Cases Require a Systematic Approach:

When NaNs are spread across both rows and columns, the optimal solution isn’t obvious. Sometimes, the best solution involves a mix of row and column removals.

This necessitates an algorithmic strategy to maximize the preserved submatrix.

2.3Linear Programming Formulation¶

The problem can be formulated using integer linear programming Wolsey, 2020, defining decision variables for removing rows, columns, and individual cells, subject to constraints ensuring all NaN values are handled. The objective is to minimize the total number of effectively removed cells, equivalent to maximizing the area of the remaining NaN-free submatrix.

Given:

A matrix of shape with elements .

Decision variables for and :

: 1 if row is removed, 0 otherwise.

: 1 if column is removed, 0 otherwise.

: 1 if cell is effectively removed (i.e., part of a removed row or column), 0 otherwise.

Constraints:

For all and :

If is NaN, then .

.

.

.

Objective Function:

Minimize the total number of effectively removed cells:

This formulation can be solved using integer linear programming solvers (e.g., GLPK Makhorin, 2012, Gurobi Gurobi Optimization, LLC, 2023, CPLEX IBM ILOG CPLEX, 2009), often interfaced via modeling languages like Pyomo Hart et al., 2011 or PuLP Mitchell et al., 2011 in Python for data science practitioners. However, its primary disadvantage is computational cost: for an matrix, the formulation uses binary variables, which becomes prohibitive for large matrices.

3Algorithm¶

OptiMask is a heuristic designed to provide near-approximations of the optimal solutions to the problem. The core idea is to compute row and column permutations such that the search for the largest non-contiguous NaN-free submatrix reduces to finding a contiguous one.

3.1Core Approach¶

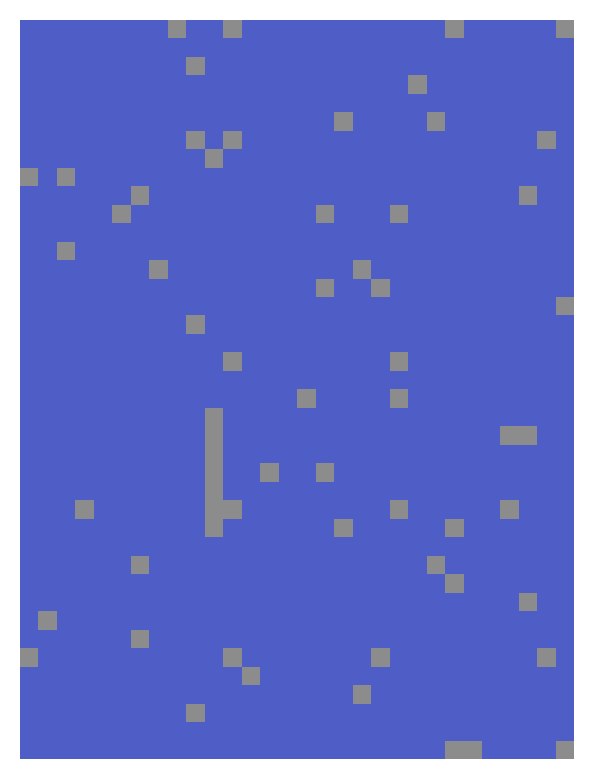

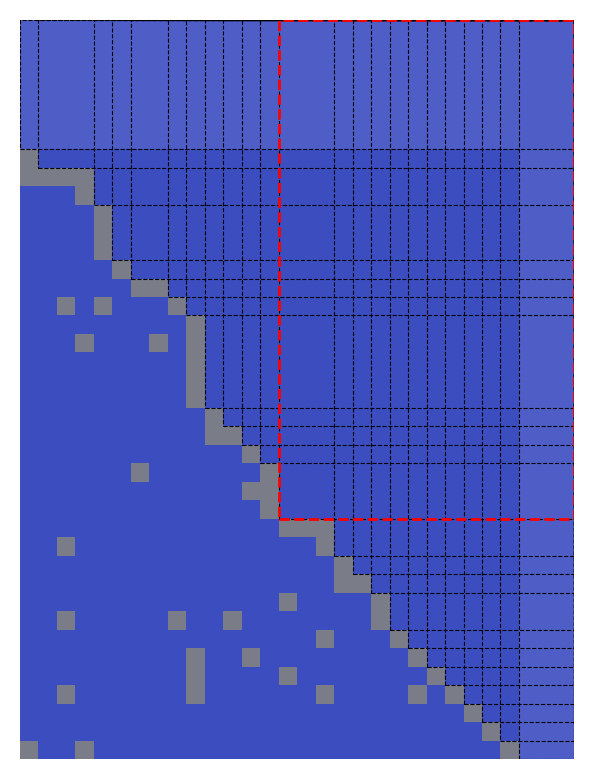

An example 40x30 matrix, containing 63 missing values, illustrating the algorithm’s steps. Grey cells represent missing values.

OptiMask employs an iterative permutation-based algorithm to identify the largest NaN-free submatrix through these key steps:

Problem Reduction:

Isolate rows and columns containing at least one NaN value (rows or columns without NaNs are preserved, as there is no reason to remove them).

Create a boolean mask matrix where True represents NaN positions.

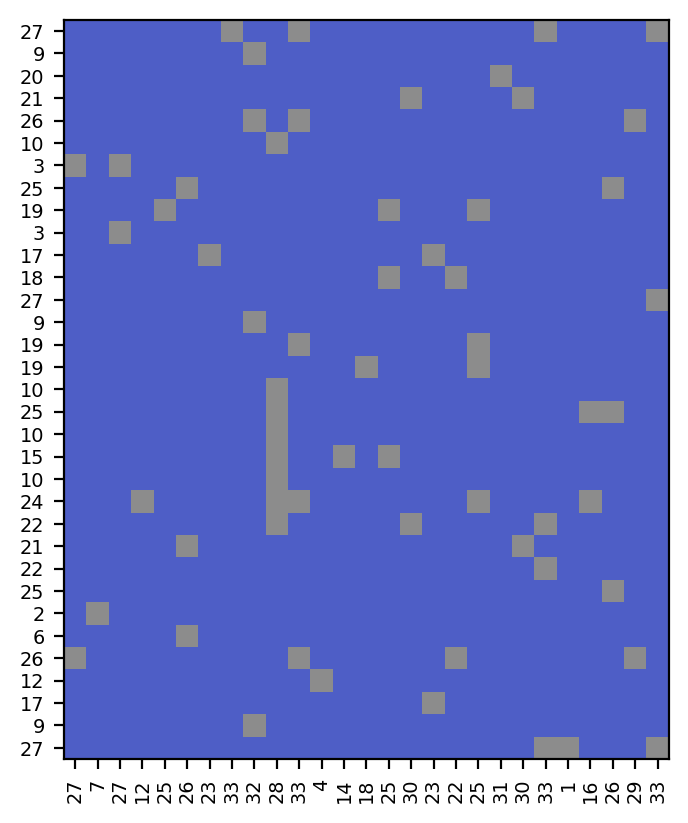

Frontier Detection:

Compute

hx: column-wise, NaN cell with highest row index (i.e., furthest bottom).Compute

hy: row-wise rightmost NaN index (from the left).These define the current “NaN frontier” of the matrix.

Steps #1 and #2: isolating the 33 rows and 27 columns with NaNs and computing

hxandhy.Permutation Phase:

Alternately sort rows and columns to push NaN values toward a Pareto frontier.

Even iterations: Sort columns by descending

hx.Odd iterations: Sort rows by descending

hy.Track all permutations applied during this process.

Repeat until both

hxandhyform non-increasing sequences, indicating an optimal NaN frontier.

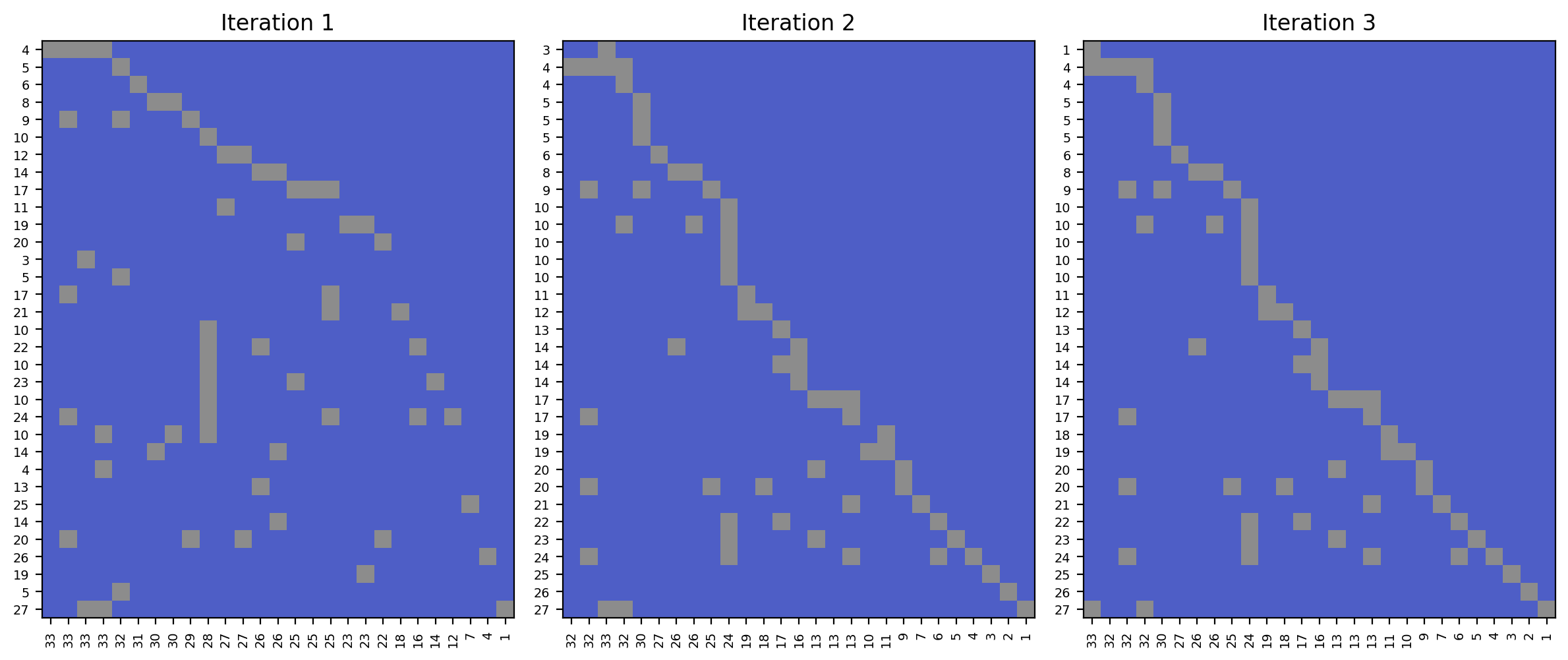

Three alternate permutations lead to a Pareto frontier of NaNs.

Submatrix Extraction:

Identify the largest contiguous NaN-free rectangle in the permuted space.

OptiMask result in permuted space: the black-dotted rectangles are candidates for the largest contiguous NaN-free submatrix, with the red-dotted one selected for its maximal area.

Apply inverse permutations to map back to original row/column indices.

OptiMask result: grey indicates missing values, red indicates removed rows and columns, blue marks the computed NaN-free submatrix. The algorithm computes a 27x17 submatrix, whereas discarding every row with NaN would result in a 7x30 submatrix, and discarding every column with NaN would yield a 40x3 submatrix.

4Python Package¶

A Python implementation of the algorithm is available on PyPI (https://

4.1Basic Usage¶

import numpy as np

from optimask import OptiMask

from optimask.utils import generate_mar

# Generate a Missing At Random matrix with 2% NaN values

x = generate_mar(m=100_000, n=1_000, ratio=0.02, rng=0)

rows, cols = OptiMask(random_state=0).solve(x)

np.isnan(x[np.ix_(rows, cols)]).any() # False

len(rows), len(cols) # (37386, 49)This computation takes approximately 200ms on an average personal computer. The implementation provides the sorted indices of the rows and columns to retain, ensuring that the relative order of the elements is preserved.

4.2Handling Missing Data for Machine Learning¶

OptiMask removes missing values (NaN) from datasets while maximizing usable data. It does this by finding an optimal subset of samples (rows) and features (columns) to discard, ensuring the remaining data contains no missing values. This makes the dataset directly usable for machine learning models that require complete data, such as scikit-learn’s linear models:

import numpy as np

from optimask import OptiMask

from sklearn.datasets import make_spd_matrix

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

def load_data_with_nan(m, n, nan_ratio):

mean = np.random.randn(n + 1)

cov = make_spd_matrix(n + 1)

data = np.random.multivariate_normal(mean=mean, cov=cov, size=m)

mask = np.random.rand(*data.shape) < nan_ratio

data[mask] = np.nan

return data[:, :-1], data[:, -1]

# Simulate a dataset with missing values

X, y = load_data_with_nan(m=10_000, n=100, nan_ratio=0.02)

# Drop samples where the target (y) is missing

valid_samples = np.isfinite(y)

X, y = X[valid_samples], y[valid_samples]

# Apply OptiMask to remove remaining NaNs

rows, cols = OptiMask().solve(X)

X_clean, y_clean = X[np.ix_(rows, cols)], y[rows]

print(X_clean.shape, y_clean.shape) # (3581, 50) (3581,)

# Train a model on the NaN-free data

model = LinearRegression().fit(X=X_clean, y=y_clean)By strategically selecting which rows and columns to keep, OptiMask ensures the dataset remains meaningful while becoming fully trainable.

5Conclusion¶

OptiMask provides a heuristic for finding the largest NaN-free submatrix in large datasets where exact methods like linear programming become computationally impractical. By strategically permuting rows and columns to isolate missing values, it offers a practical solution that preserves maximal data without imputation. The Python implementation supports common data structures (numpy, pandas, polars) and delivers results efficiently even for large matrices.

Future work will explore theoretical guarantees on the approximation quality and extensions to weighted optimization problems. The implementation will continue to be optimized for speed in subsequent versions. Finally, an OptiMask-based algorithm for tabular imputation will be developed and benchmarked against MICE (Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations, White et al., 2011) to evaluate whether it can achieve better or faster results.

This work was funded by Airparif. I’d like to thank Paul Catala (Université de Lorraine) and Alexis Lebeau (RTE) for their assistance and review.

Copyright © 2025 Joly. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- NaN

- Not a Number

- Little, R. J., & Rubin, D. B. (2019). Statistical analysis with missing data (Vol. 793). John Wiley & Sons. 10.1002/9781119482260

- Rubin, D. B. (2004). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys (Vol. 81). John Wiley & Sons. 10.1002/9780470316696

- Schafer, J. L. (1997). Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. CRC press. 10.1201/9781439821862

- Van Buuren, S. (2018). Flexible imputation of missing data. CRC press. 10.1201/9780429492259

- White, I. R., Royston, P., & Wood, A. M. (2011). Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine, 30(4), 377–399. 10.1002/sim.4067

- Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford press. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2012.00656.x

- Wolsey, L. A. (2020). Integer programming. John Wiley & Sons. 10.1002/9781119606475

- Makhorin, A. (2012). GLPK (GNU linear programming kit). http://www.gnu.org/software/glpk/

- Gurobi Optimization, LLC. (2023). Gurobi Optimizer Reference Manual. https://www.gurobi.com

- IBM ILOG CPLEX. (2009). V12. 1: User’s Manual for CPLEX (53, Vol. 46, p. 157). International Business Machines Corporation.

- Hart, W. E., Watson, J.-P., & Woodruff, D. L. (2011). Pyomo: modeling and solving mathematical programs in Python. Mathematical Programming Computation, 3(3), 219–260. 10.1007/s12532-011-0026-8

- Mitchell, S., OSullivan, M., & Dunning, I. (2011). PuLP: a linear programming toolkit for python. https://pythonhosted.org/PuLP/

- Lam, S. K., Pitrou, A., & Seibert, S. (2015). Numba: A llvm-based python jit compiler. Proceedings of the Second Workshop on the LLVM Compiler Infrastructure in HPC, 1–6. 10.1145/2833157.2833162

- Harris, C. R., Millman, K. J., Van Der Walt, S. J., Gommers, R., Virtanen, P., Cournapeau, D., Wieser, E., Taylor, J., Berg, S., Smith, N. J., & others. (2020). Array programming with NumPy. Nature, 585(7825), 357–362. 10.1038/s41586-020-2649-2

- McKinney, W., & others. (2010). Data structures for statistical computing in python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, 445, 51–56. 10.25080/Majora-92bf1922-00a