On the Path to Seamless Python Serverless Data Analytics

Abstract¶

Traditionally, most data scientists rely heavily on clusters of virtual machines to handle large-scale workloads. While these clusters are effective, they entail substantial operational and maintenance costs, alongside increasing complexity in configuration and scaling — often demanding dedicated infrastructure specialists.

The rise of the serverless paradigm introduced a radically different model, centered on functions with automatic scaling and pay-per-use billing. To enable data analytics on serverless architectures, Lithops emerges as a powerful Python framework that abstracts away infrastructure complexities, empowering seamless parallel execution through serverless functions and allowing users to focus purely on their code.

A persistent challenge in serverless data analytics is the need to partition scientific data formats that were not natively designed for cloud computing. Proper partitioning is a crucial factor for maximizing parallelism and minimizing latency in data transfer from storage to compute resources. Dataplug addresses this by enabling on-the-fly partitioning for non-cloud-native data formats, optimizing data distribution among workers.

To further streamline the scientific development experience, we tackle the steep learning curve posed by configuring and managing serverless environments for users without DevOps expertise. We present PyRun: a browser-based IDE offering the familiar interface of notebook tools (e.g., JupyterLab, Google Colab) but with native cloud integration. PyRun drastically reduces the cognitive burden of setup — delivering a ready-to-execute environment with zero configuration required.

Ultimately, the integration of Lithops, Dataplug, and PyRun forms a compelling stack that unlocks the full potential of serverless data analytics in Python, delivering clear and transformative benefits to scientific workflows.

1From Cluster-Centric to Serverless Data Analytics¶

Data analytics has traditionally been conducted on clusters—networks of interconnected servers collaboratively processing and analyzing vast volumes of data. These clusters deliver the computational power, storage capacity, and parallelism necessary to address the growing scale and complexity of datasets across diverse domains such as finance, healthcare, and social media. By distributing workloads across multiple nodes, clusters enable efficient parallel execution, fault tolerance, and scalability, establishing themselves as the backbone of many big data frameworks like Apache Hadoop Shvachko et al., 2010 and Apache Spark Zaharia et al., 2016. The cluster-centric approach has proven effective for batch processing and iterative algorithms that demand high throughput and sustained computational resources.

Nonetheless, inherent limitations persist within this architecture for data analytics workloads. Resource overprovisioning is commonplace, resulting in suboptimal and inefficient utilization. This inefficiency is particularly pronounced in scenarios with infrequent analytics executions, where users maintain clusters in a ready state without active workloads. Scalability also remains a critical challenge: server provisioning and deprovisioning often incur latencies of several minutes Barcelona-Pons et al., 2025, underscoring limited resource elasticity. Furthermore, the operational complexity and maintenance overhead of cluster-based frameworks such as Spark and Hadoop necessitate specialized expertise to configure, optimize, and sustain the computing environment.

Conversely, simpler computing models have emerged, notably with the introduction of Function-as-a-Service (FaaS) by AWS in 2014. This paradigm abstracts infrastructure management entirely, allowing developers to focus solely on their application logic. Additional advantages—including a pay-as-you-go pricing model and low invocation latencies—have sparked significant interest within the scientific community. While FaaS was not originally designed with data analytics workloads in mind, its potential for scalable and parallel computation has motivated investigations into its viability as a core engine for distributed data analytics applications.

2Lithops: The Pythonic Serverless Data Analytics Framework¶

Despite the previous suggested potential, leveraging FaaS platforms for large-scale data analytics presents several inherent challenges. These include the lack of direct peer-to-peer communication between functions, the absence of native synchronization mechanisms between stages (like in a MapReduce model), difficulties in managing dependencies and libraries across different cloud environments, and a general lack of portability due to proprietary APIs. The initial efforts on serverless data analytics field partially addressed these issues Jonas et al., 2017, but they often fell short of providing a comprehensive solution.

Lithops Sampé et al., 2023 entered to scene to tackle these challenges in a unified manner. Lithops is a serverless, multi-cloud framework designed for building both embarrassingly parallel and MapReduce-like applications using cloud functions. Lithops empowers users, even those without extensive cloud expertise, to effortlessly port their programs—from Monte Carlo simulations to analytics workflows—to the cloud. By transparently orchestrating hundreds of concurrent function instances, Lithops enables significant performance gains for "occasional" cloud users who might otherwise be daunted by the complexities of cluster resource provisioning.

From the programming perspective, Lithops addresses the aforementioned challenges by implementing a simple MapReduce interface that allows single-machine Python code to be executed as parallel jobs in the cloud. It also includes an intuitive storage API to facilitate communication between functions and with the Lithops client. Synchronization between map and reduce stages, including nested function compositions, is handled implicitly, reducing user burden, and Lithops automatically manages dependencies by leveraging Python’s dynamic nature. Finally, its architecture is designed to abstract away cloud provider specifics, ensuring multi-cloud portability and mitigating vendor lock-in across platforms like IBM Cloud, Google Cloud and AWS.

In essence, Lithops provides a unified system to leverage cloud functions for massively-parallel execution of programs, enabling hundreds-way parallelism on short-lived functions and significantly accelerating everyday and scientific computing tasks.

2.1Architecture¶

The core design of Lithops is centered around abstracting the complexities of cloud functions and providers to offer a seamless experience for parallel program execution. At its heart, Lithops operates as a multi-cloud framework, capable of deploying and managing functions while abstracting away the underlying cloud interface. This multi-cloud capability is a fundamental architectural choice, that mitigates vendor lock-in and offering users same interface across different choices.

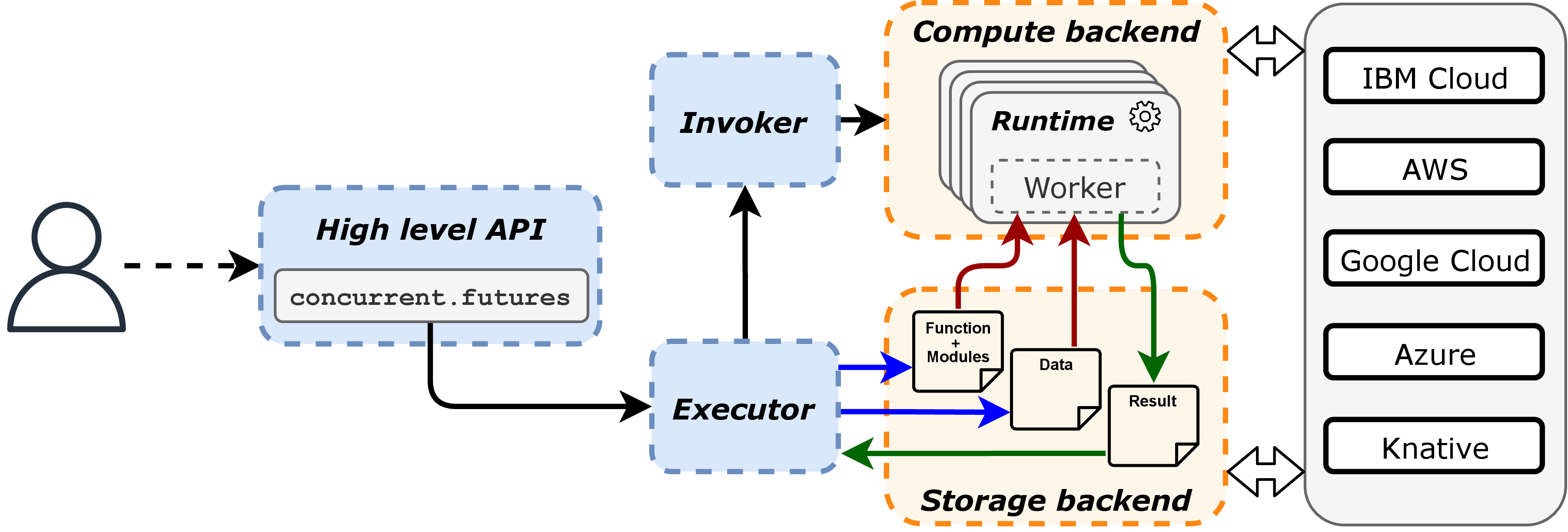

A picture of the Lithops architecture is shown in Figure 1. The components can be initially splitted into two main categories: local components (blue) which run on the user’s host, and remote components (orange) which run on the cloud provider in the form of serverless functions. On local side, the user uses the Futures API to submit jobs, which are then orchestrated by the Executor, which push/pull resources to/from the cloud provider, and manages the execution of the functions. Meanwhile, the Invoker is the component responsible for invoking the remote Workers, whose runtime is aware of the Lithops framework and can execute the user code remotely in a transparent way.

Figure 1:Lithops Architecture Overview

The typical operational flow of Lithops is as follows:

The user submits a job using the Futures API, which is handled by the Executor.

The Executor partitions the job into smaller tasks and push the necessary data and dependencies to the object storage.

The Invoker creates the remote workers, which pull the user code and dependencies from the object storage.

The remote Workers read the input data from the object storage, execute the user code, and write the results back to the object storage.

The Executor pulls the results from the object storage and returns them to the user.

The user can then retrieve the results from the Futures API.

Overall, the Lithops architecture follows a layered design, where the (client) framework layer builds on top of the serverless execution layer. This design effectively addresses the constraints of the serverless model by providing a unified and abstracted interface for large-scale parallel computing, enabling users to focus on their code and logic while the framework manages the orchestration and infrastructure transparently.

2.2Programming Model¶

Lithops exposes a set of high-level APIs that simplify access to both compute and storage backends. The key interfaces are outlined below.

Futures API. Lithops offers a simple yet powerful programming model that enables users to transform single-machine Python code into massively parallel, cloud-based executions. The primary objective of this model is to substantially lower the entry barrier for adopting cloud Function-as-a-Service (FaaS) platforms, especially for workloads that exhibit natural parallelism, similar to the MapReduce paradigm. To support this, the Lithops Futures API provides the map() function, which launches multiple workers to execute the same function across different data partitions. Building on this, the map_reduce() function extends this functionality by executing a final reduce function that gathers and processes the outputs from the map phase.

"""

Simple Lithops example using the map() call to estimate PI

"""

import lithops

import random

def is_inside(n):

count = 0

for i in range(n):

x = random.random()

y = random.random()

if x*x + y*y < 1:

count += 1

return count

if __name__ == '__main__':

np, n = 10, 15000000

part_count = [int(n/np)] * np

fexec = lithops.FunctionExecutor()

fexec.map(is_inside, part_count)

results = fexec.get_result()

pi = sum(results)/n*4

print("Estimated Pi: {}".format(pi))The code snippet above illustrates a straightforward example of using the Lithops framework to estimate the value of , using the Monte Carlo method. It first defines the quarter of a circle with radius 1, specifically that of the first quadrant. The algorithm then randomly generates points within the unit square of this quadrant. We can simply know if a point falls within the circle by checking if the coordinates satisfy the equation . As the area of the quarter circle is , we can expect approximately that proportion of the points to fall within it. Therefore, we can estimate by calculating the ratio of points that fall inside the circle to the total number of points.

Because each point calculation is completely independent, Lithops can run thousands of these trials in parallel across different workers, dramatically speeding up the estimation by simply summing their individual results. First, an instance of lithops.FunctionExecutor() is created. The map() method then launches multiple serverless functions that execute the is_inside() function concurrently, each processing a portion of the input data. Once all tasks complete, get_result() collects the results from the distributed execution and receives them locally, enabling the user to obtain the final estimation seamlessly.

Analogously to how is estimated through the parallel execution of multiple functions, Lithops enables users to apply this pattern to a wide range of parallel computing problems, as simple as demonstrated in this example. While the core Lithops framework provides fundamental operators like MapReduce, it is part of a comprehensive software stack that significantly extends its capabilities. As we will explain throughout this work, this stack includes IO abstractions that serve as building blocks for group communication patterns, alongside a public workload registry offering programmatic examples of more complex operations such as joins and sorts.

Storage API. Lithops not only aims to simplify the experience of executing parallel code on serverless platforms, but also abstracts away data access operations—typically performed over object storage. Whether interacting from the Lithops client or from remote workers, the Storage API provides a unified interface that, like the Futures API, avoids vendor lock-in.

In practice, this means that users can write code that works seamlessly not only across object storage from different cloud providers, but also with memory storage systems like Redis Sanfilippo & community, 2009. The following snippet shows a minimal working example—writing an object to storage and then reading it back—that operates seamlessly across all cloud providers supported by Lithops

from lithops import Storage

if __name__ == "__main__":

st = Storage()

st.put_object(bucket='mybucket', key='test.txt', body='Hello World')

print(st.get_object(bucket='mybucket', key='test.txt'))

2.3High-Performance Insights¶

Practical baseline performance. Several features make Lithops particularly well-suited for some high-performance parallel data analytics workloads, enabling users not only to execute large-scale computations with minimal effort but also leverage serverless computing upsides. When leveraging the map() primitive, users distribute their data processing tasks across numerous cloud functions, that presents key highlights that make it stand out, as presented below:

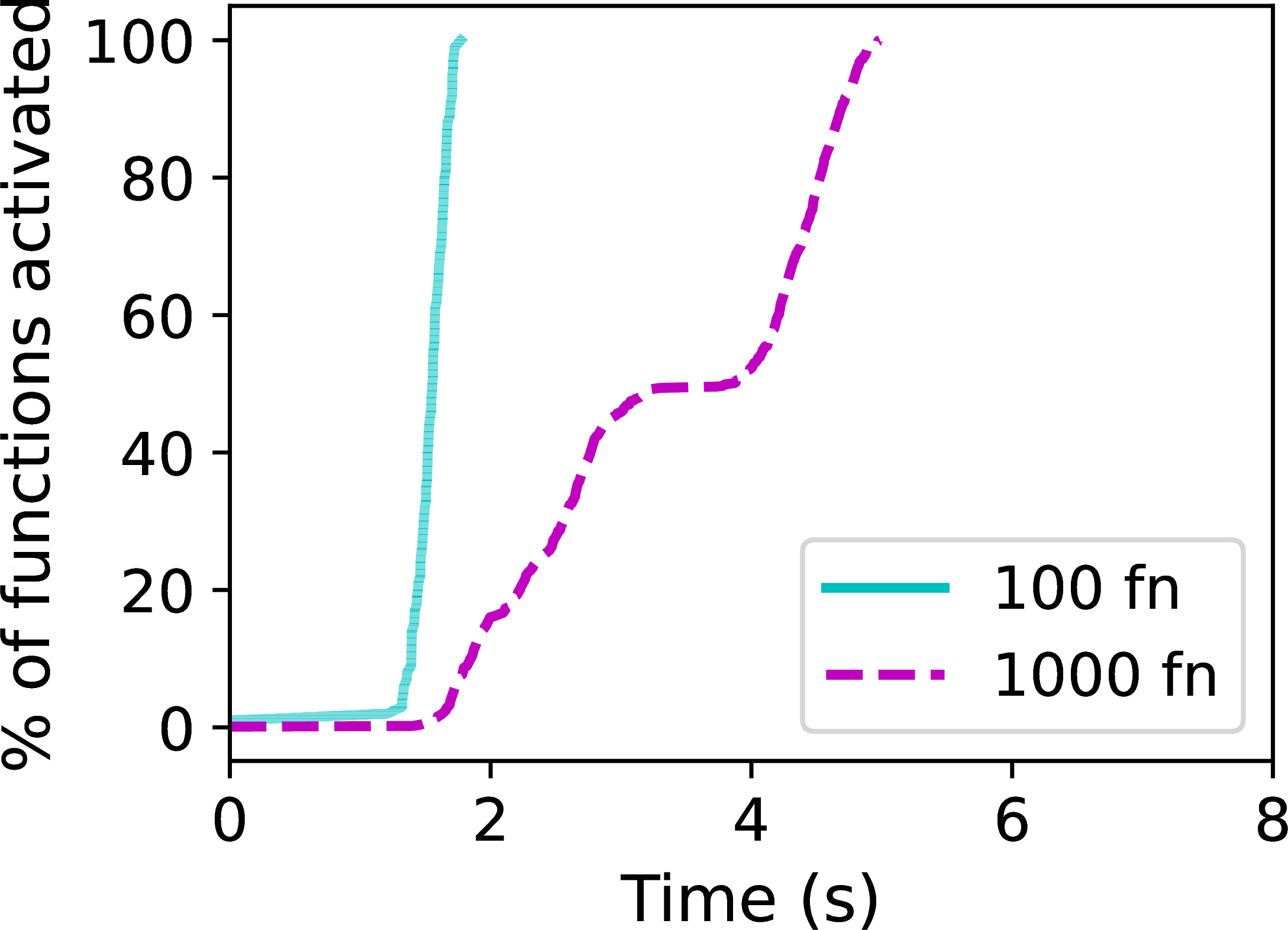

Figure 2:Lithops performance: invocation latency (a) and aggregate bandwidth (b).

The elasticity of Function-as-a-Service (FaaS) platforms when launching functions is a key performance feature. As shown in Figure 2, we observe that 100 AWS Lambda functions are instantiated and start executing in less than 2 seconds; for 1000 functions, this delay increases only up to 5 seconds. The ability to scale from zero to thousands of vCPUs in such a short amount of time offers a level of burstiness previously unseen in traditional cluster environments.

Once the compute resources (FaaS functions) are instantiated, they typically load their input data from object storage. As depicted in Figure 2b, the aggregate bandwidth offered by Amazon S3 reaches up to 100 GB/s for reads and 90 GB/s for writes when accessed concurrently by 1000 functions. This demonstrates the S3 high I/O parallelism, which Lambda functions can efficiently leverage for highly scalable data pull/push operations.

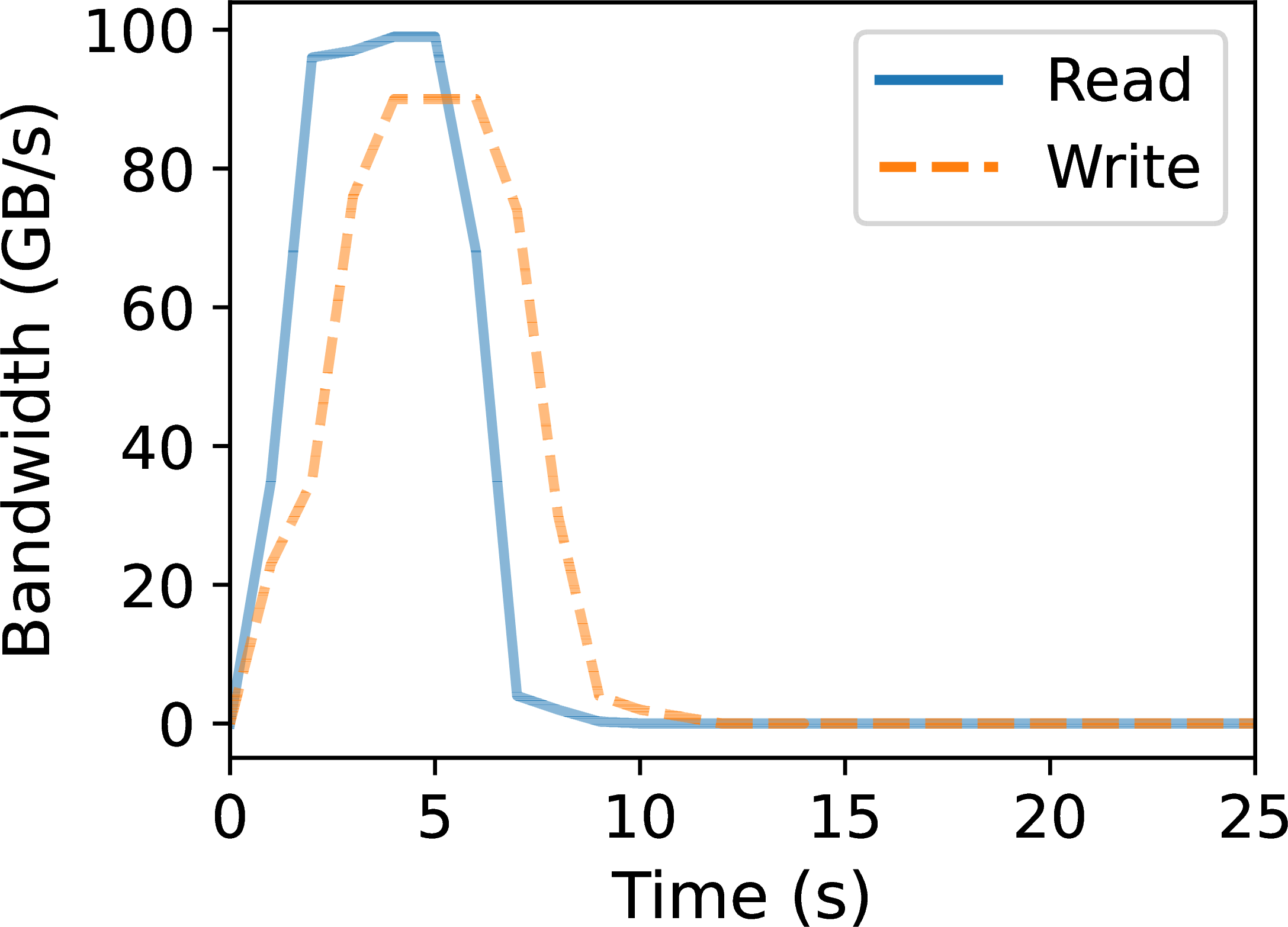

Leveraging effective transparency. As previously stated, Lithops leverages AWS Lambda and S3 as its default backend, yet its design is not dependent on these specific services. To evaluate its architectural flexibility, we design an I/O-intensive analytics experiment that outlines three key aspects: (1) the performance characteristics of Lithops’ default AWS Lambda and S3 configuration, (2) its seamless integration capabilities with alternative cloud providers and services, and (3) the practical transparency achieved through its abstracted Storage API.

For our experimental evaluation, we employ a 5GB TeraSort workload. This benchmark is I/O-intensive, comprising two parallel stages of functions connected by an all-to-all communication pattern. We conduct this experiment across three distinct setups:

AWS Lambda utilizing AWS S3 for intermediate storage.

Google Cloud Run utilizing Google Cloud Storage for intermediate storage.

AWS Lambda utilizing Redis as the intermediate storage. To streamline deployment and management, we provision Redis as an AWS ElastiCache Amazon Web Services (AWS), 2025 managed cluster.

Crucially, the experimental methodology maintains identical application code across all three setups, based on the original implementation detailed in Sánchez-Artigas & Eizaguirre (2022). This serves as a direct demonstration of Lithops’ transparency and portability. The only difference is the Lithops configuration file, which specifies the cloud provider and the storage backend to use.

Our empirical results, depicted in Figure 3, show that Google Cloud Run exhibits demonstrably inferior performance compared to the AWS-based configurations. Conversely, the performance of AWS Lambda with S3 is marginally slower than that of AWS Lambda with Redis, underscoring the competitive performance of Lithops’ default setup. However, it is important to note that execution variability was significantly higher when using S3, which can likely be attributed to the throughput constraints associated with object storage systems.

Figure 3:TeraSort performance of Lithops across different cloud providers and storage backends (in parentheses).

2.4Source code¶

The entire Lithops source code is openly accessible to the public via its GitHub repository: https://

3Optimized Data Partitioning with Dataplug¶

Scientific computing in the cloud is becoming increasingly data-driven. The success of large-scale data-parallel workloads depends not only on scalable computation, but also on scalable data access. In this section, we examine the limitations of traditional static data partitioning, introduce the concept of cloud-aware formats, and describe how the Dataplug Arjona et al., 2024 framework enables dynamic on-the-fly partitioning of unstructured scientific data. We conclude with an overview of Dataplug operational flow, allowing users to efficiently access and process large unstructured scientific datasets.

3.1Static Partitioning¶

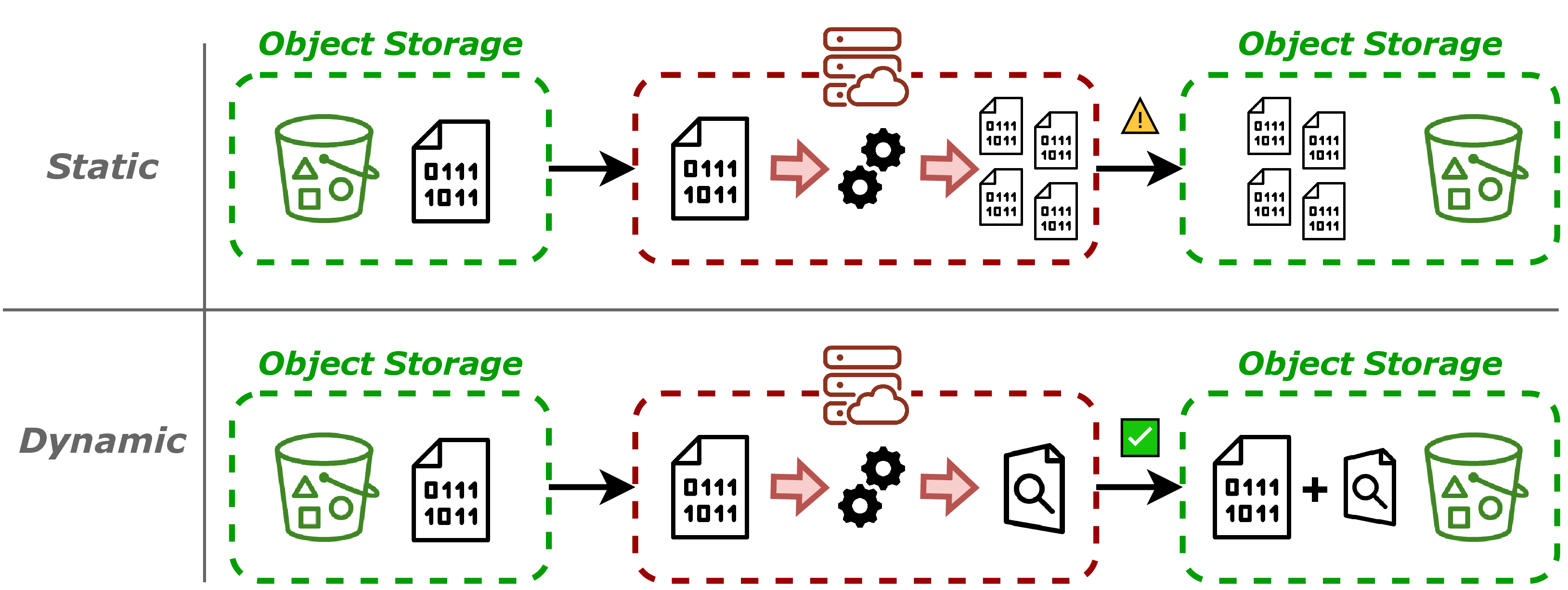

Static data partitioning is the traditional approach to data distribution in parallel serverless computing. It consists of physically splitting datasets into smaller chunks ahead of time, often based on size (e.g., 1 GB per file), and storing these chunks as individual objects (as shown on top of Figure 4). This enables distributed execution frameworks like Lithops or Dask Rocklin, 2015 to process data in parallel by assigning each file to a separate worker.

While conceptually simple, static partitioning comes with significant limitations:

High preprocessing cost: Partitioning usually requires reading, transforming, and re-writing large datasets back to storage. In cloud object storage, where data is immutable, this implies full data duplication, leading to high I/O, storage, and compute costs.

Inflexibility: Once partitioned, the chunk size is fixed. Adapting to new workloads (e.g., smaller partitions for finer-grained parallelism or larger ones for fewer tasks) requires reprocessing and rewriting the dataset again.

These limitations become increasingly problematic as scientific datasets grow to the huge scale. In practice, many research teams cannot afford the cost of rewriting legacy datasets just to enable parallel access. Moreover, partitioning choices made early in a project may later hinder performance optimization, preventing effective use of scalable resources.

Figure 4:Static and dynamic partitioning approaches.

3.2Cloud-Aware Formats Approach¶

One proposed solution to partitioning data is to adopt so-called cloud-optimized formats. These are file formats specifically designed to support partial reads (i.e. queries) using HTTP range requests over object storage. Examples include some Cloud-Optimized Formats as Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFF (COG) and Cloud-Optimized Point Cloud (COPC). These formats allow users to access data in parallel without needing to rewrite it, as they can be read directly from object storage using HTTP range requests. This enables efficient data access patterns, such as reading only the required chunks for a specific analysis, without incurring the cost of full dataset duplication.

While effective, this approach has its own challenges. Converting existing datasets to cloud-optimized formats requires a full rewrite of the data, which can be prohibitively expensive for huge-scale archives. Moreover, not all scientific formats support casting to a cloud-optimized format—for example, text-based genomic formats like FASTQ or compressed binary LAS files for spatial data.

So, the alternative head towards a new model: dotate legacy formats with cloud-awareness, enabling dynamic partitioning without rewriting the data. This approach allows users to access and process large datasets in parallel without incurring the high costs of static partitioning.

3.3Dataplug: Enabling Dynamic Partitioning in Scientific Formats¶

Dataplug is a Python framework that implements cloud-aware, on-the-fly dynamic partitioning model. The key idea is to maintain legacy data blobs without modification while enabling efficient access patterns. Rather than rewriting the data into a new format, Dataplug extracts structural metadata from the raw files via read-only preprocessing and stores this information externally (e.g., in a database or a metadata bucket). This enables parallel access to the original object without modifying it.

There are three essential building blocks that, in turn, compose the three key directives of the Dataplug framework.

Cloud-aware preprocessing (flow shown in bottom of Figure 4): Each supported format defines a preprocessing heuristic that analyzes the file structure (e.g., sequence boundaries, block offsets, spatial extents) and generates the metadata. This process is one-time and non-intrusive—it never rewrites the input data.

Partitioning strategies: Once preprocessed, a dataset can be partitioned in multiple ways using user-defined strategies. A partitioning function queries the metadata and defines logical partitions (called slices). For instance, one strategy might divide genomic data into 1 million reads per slice, while another partitions spatial files by bounding box. These strategies are pluggable and workload-specific.

Lazily-evaluated slices: Each slice represents a logical data partition. When a worker performs the get operation over the slice, it retrieves the corresponding byte ranges from object storage (using HTTP range requests) to the worker memory. This happens entirely at runtime, just-in-time for processing.

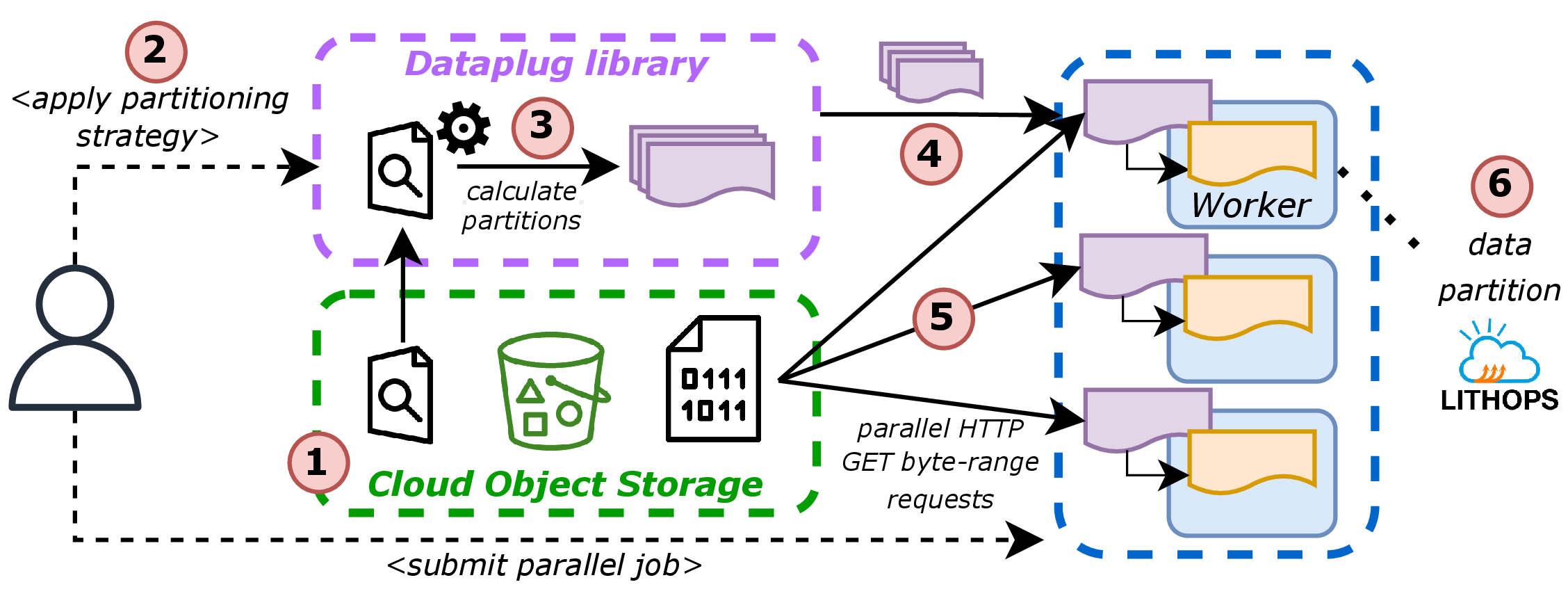

The partitioning and getting of slices mechanism is illustrated in Figure 5.

from dataplug import CloudObject

from dataplug.formats.genomics.fastq import FASTQGZip, partition_reads_batches

# Assign FASTQGZip data type for the object

co = CloudObject.from_s3(FASTQGZip, "s3://genomics/dataset.fastq.gz")

# Data must be pre-processed first ==> This only needs to be done once per dataset

co.preprocess()

# Partition the FASTQGZip object into 200 chunks

# This does not move data around, it only creates data slices from the indexes

data_slices = co.partition(partition_reads_batches, num_batches=200)

def process_fastq_data(data_slice):

# Evaluate the data_slice, which will perform the

# actual HTTP GET requests to get the FASTQ partition data

fastq_reads = data_slice.get()

...

# Use Lithops to process the data slices in parallel

from lithops import FunctionExecutor

with FunctionExecutor() as fexec:

# Map the process_fastq_data function to each data slice

fexec.map(process_fastq_data, data_slices)At the same time, the entire workflow explained in previous lines is straightforward to use via Dataplug API. The above code snippet illustrates how to use Dataplug to partition one genomic (FASTQGZip) file into several slices, and then process each slice in parallel using Lithops. In a very quick overview, the code above illustrates how to use Dataplug to partition a FASTQGZip file into 200 slices, and then process each slice in parallel using Lithops. First, the preprocess() method generates the required metadata for the FASTQGZip file, then the partition() method creates the slices based on the specified partitioning strategy, and the get() method retrieves the data for each slice when called, in a lazy way.

Figure 5:Dataplug workflow.

Dataplug approach offers several key advantages over static partitioning, that make it particularly well-suited for scientific data analytics:

Zero-cost repartitioning: Because partitioning operates over metadata, the same dataset can be re-sliced on demand with different strategies, without re-reading or re-writing the raw data.

Efficient resource usage: The metadata is lightweight (often of the original file size), and slices can be distributed to any number of workers, enabling elastic autoscaling.

Format extensibility: Support for new formats is added by implementing a preprocessor, a strategy, and a slice handler—without need to modify the core.

3.4Source code¶

The entire Dataplug source code is openly accessible to the public via its GitHub repository: https://

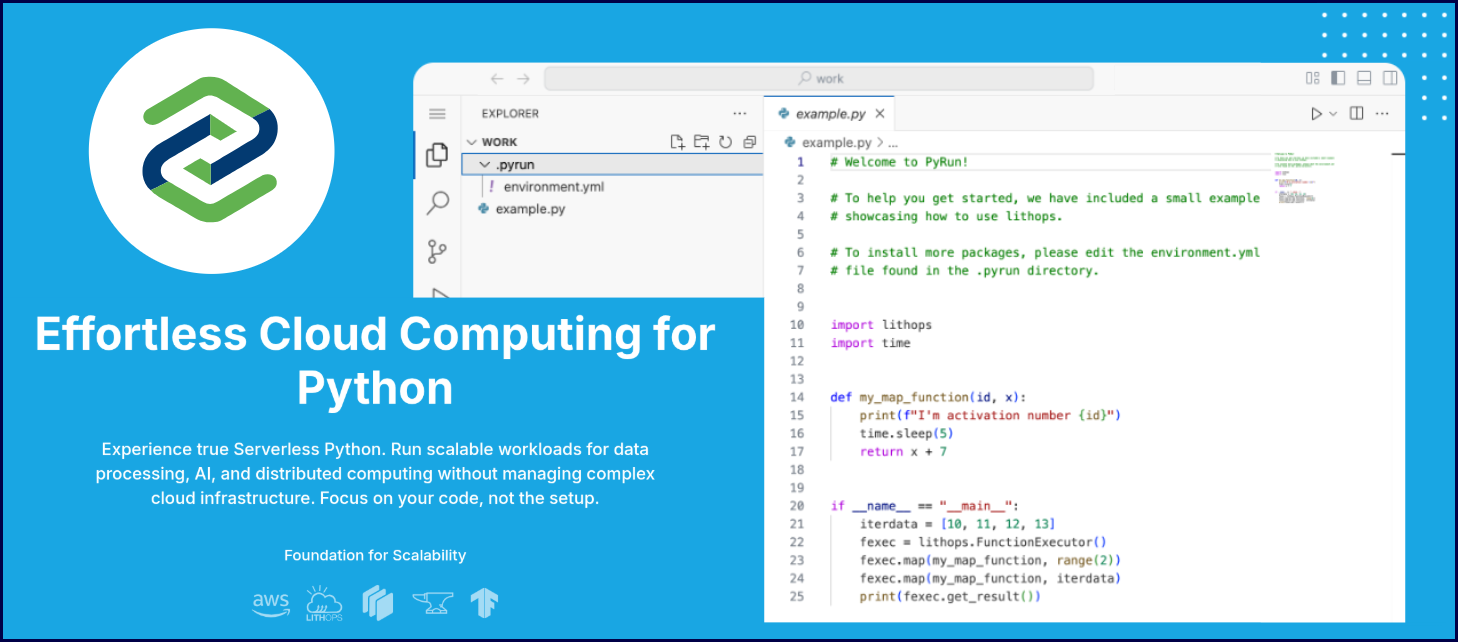

4PyRun: Simplifying Serverless Environments for Data Science¶

In the same plane as serverless computing, which minimizes the infrastructure management burden, PyRun emerges as an integrated development environment (IDE) that further simplifies the development and execution of applications, particularly in the context of data science and scientific computing. By providing a ready-to-use, browser-based development environment, PyRun eliminates the need for users to configure or manage infrastructure, making it accessible even to those without DevOps experience. With a minimal configuration step, users can quickly set up their cloud environment and start developing applications without the complexities typically associated with cloud computing.

At a glance, the PyRun environment offers the following features:

Ready-to-execute Web IDE: For each PyRun application, users are provided with a fully remote, web-based development environment accessible via browser. This environment is also natively synchronized with GitHub, enabling a seamless development workflow without the need for local installations. PyRun delivers a practical interface through an interactive programming notebook, similar to established tools like JupyterLab Jupyter Development Team, 2025 or Google Colab Google LLC, 2025, but with the added benefit of being pre-configured for cloud execution and automatic, cross-service runtime management.

Pre-configured frameworks: PyRun currently supports native integration with parallel computing frameworks such as Lithops, Das and Dataplug, with plans to extend this list in the future. These integrations allow users to access powerful APIs without the overhead of manual pre-configuration, significantly accelerating the development and deployment process.

Collaborative and Reproducible Workflows: PyRun’s Public Resources feature promotes scientific collaboration and reproducibility by allowing users to share parallel applications and pipelines with the broader community. These shared resources also serve as a valuable compendium of programmatic patterns, which developers can adapt as building blocks for their own solutions.

Monitoring: PyRun provides a built-in observability layer for scientific parallel applications. Users have access to a monitoring interface that displays detailed execution metrics, including task status, CPU/memory/network usage, failure reports, and runtime statistics.

Simplified AI/ML workflows: PyRun facilitates AI/ML development by offering an integrated environment with automated infrastructure management. It supports widely-used machine learning frameworks such as TensorFlow and PyTorch, with straightforward runtime configuration. Scalable training and data processing can be achieved through Lithops-based distributed execution. Additionally, PyRun includes support for interactive LLM experimentation, allowing users to run models such as LLaMA 3 locally via Ollama within their workspace.

In summary, PyRun is a platform that simplifies the development and execution of serverless, data analytics and AI/ML applications. For further details, visit https://

5Case Study: Python Serverless Data Analytics Empowering METASPACE Metabolomics Pipelines¶

One prominent example of leveraging serverless data analytics in Python is METASPACE Alexandrov et al., 2019, a cloud platform developed by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) to support spatial metabolomics research. This field aims to identify and localize small molecules—such as metabolites and lipids—within tissue sections using imaging mass spectrometry (MS). These spatial insights are critical for understanding biological processes related to disease, development, and immune response

METASPACE allows researchers to submit MS datasets, automatically annotate detected molecules, and visualize their spatial distribution. It provides standardized quality control, enabling comparisons across experiments, laboratories, and instruments. The platform has evolved into a community-driven knowledge base of spatial metabolomes, supporting open data sharing and collaboration. With over 1,000 users and tens of thousands of processed datasets, METASPACE has become a widely adopted tool in biomedical research, making spatial metabolomics more accessible, reproducible, and scalable.

5.1Lithops for Elasticity¶

METASPACE initially relied on a Spark cluster for its computational backend. However, as user numbers grew and workloads became more demanding, the limitations of this setup became increasingly evident. Spark’s static resource allocation and rigid execution model made it difficult to handle large, diverse datasets efficiently. This often led to resource underutilization or performance bottlenecks, restricting the system’s ability to scale effectively.

To address these issues, METASPACE transitioned to a serverless architecture, aiming for greater elasticity and ease of management. By adopting Lithops, the platform gained the ability to scale computing resources dynamically based on workload demands. This move significantly reduced operational overhead while improving performance and resource efficiency. The switch to a serverless model allowed METASPACE to overcome the constraints of its Spark-based infrastructure and provided a more responsive and scalable environment for data processing.

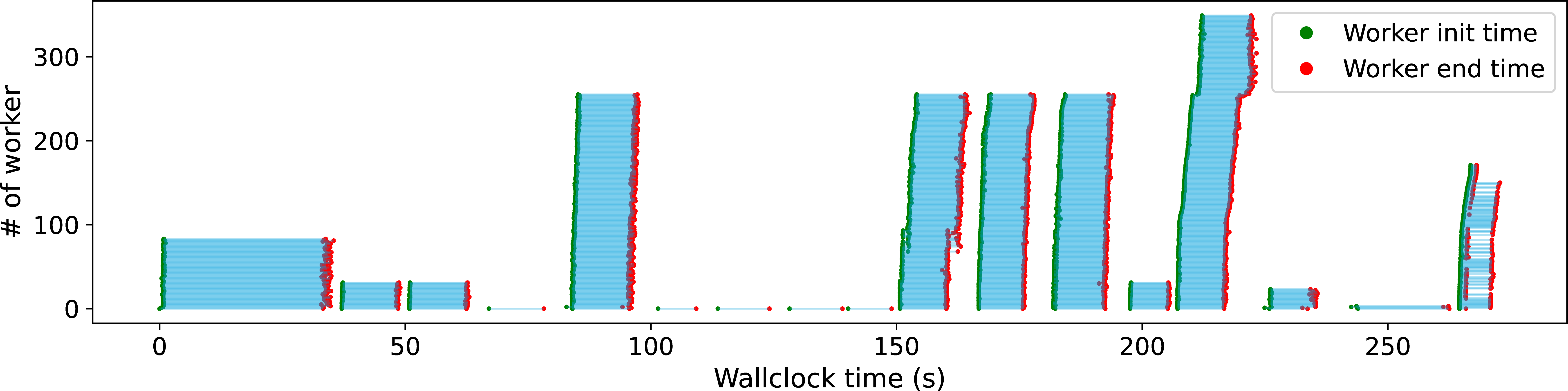

Figure 7:Execution timeline for the METASPACE metabolomics pipeline.

Figure 7 shows the execution timeline for a METASPACE metabolomics workload, a complex workflow with multiple parallel stages. The timeline reveals significant variability in resource requirements, with some steps requiring substantially more computational power than others. This fluctuation is a key driver for adopting serverless computing, a paradigm where Lithops excels by dynamically scaling resources to precisely match the needs of each pipeline step.

5.2Dataplug for Dynamic Partitioning¶

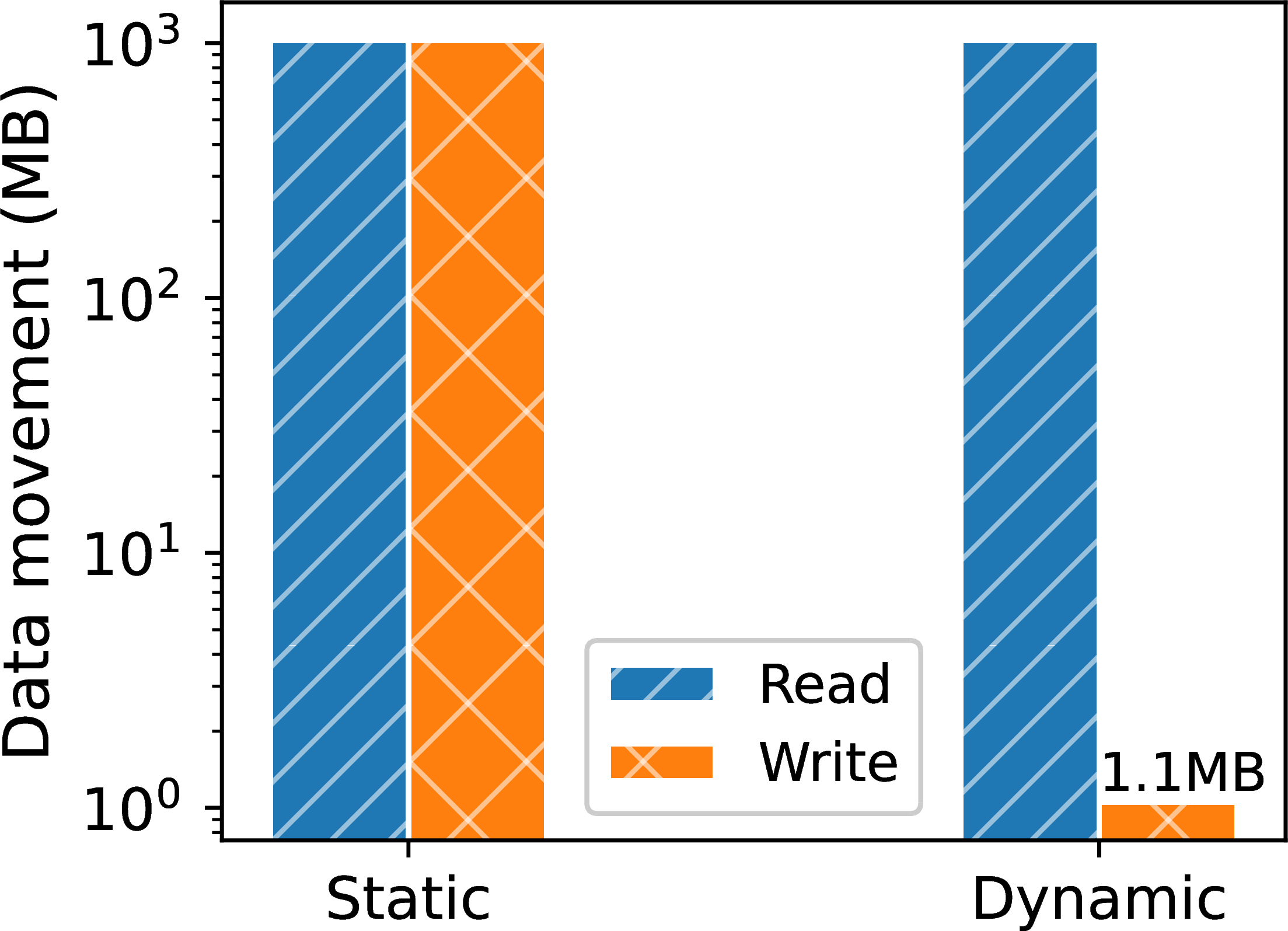

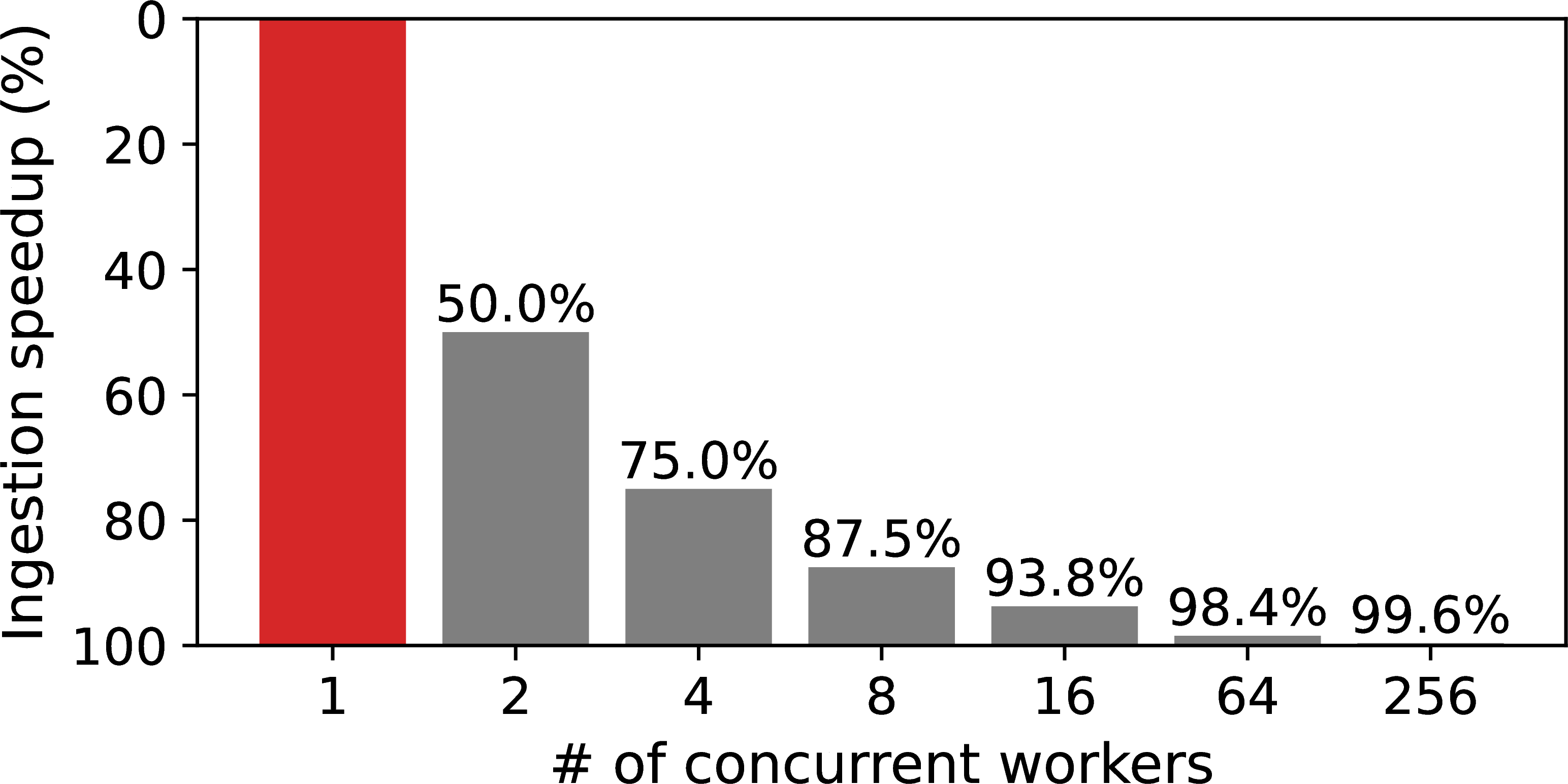

Figure 8:Dataplug performance: preprocessing and ingestion.

A common issue in metabolomics involves processing large, non-cloud-optimized datasets, such as files in the standard imzML format Schramm et al., 2012. While widely used for mass spectrometry imaging, imzML lacks native support for cloud-aware access patterns. The Dataplug framework overcomes this limitation with a plugin that enables efficient, on-the-fly partitioning of imzML files. By extracting key metadata, Dataplug facilitates dynamic partitioning strategies tailored to the specific need of each workload, eliminating the need to create static, pre-processed data chunks. This approach yields significant advantages: it reduces preprocessing time and storage costs (Figure 8) and enables parallel data access, which drastically cuts data ingestion times (Figure 8b). Furthermore, it offers researchers the flexibility to experiment with different partitioning schemes without modifying the original dataset.

5.3Practical Insights of a Serverless-native Architecture¶

To better illustrate the structural benefits of using Lithops, we compared the performance of the original METASPACE Spark-based pipeline with the new Lithops-based implementation. For the Spark execution we used PySpark over the original cluster by EMBL, consisting on four c5.4xlarge AWS EC2 instances. This architecture provided a sum of 64 vCPUs and 128GB of physical memory. We measured the performance, average CPU usage and cost of both deployments. We could assess the resource usage of the Lithops implementation by using the Lithops monitoring [1] interface, which provides detailed metrics on CPU usage (along with memory and network) for each function invocation. The cost was calculated based on the AWS Lambda pricing model, which charges per 1s of execution time and per GB of memory used, and we included the read/write requests to the S3 object storage, which are charged separately.

Table 1:Execution insight comparison of the PySpark and Lithops deployments of the METASPACE pipeline.

| Architecture | Execution Time (min) | Cost ($) | Avg Resource Usage (%) |

| PySpark | 14.21 | 0.66 | 54.56 |

| Lithops Serverless | 4.87 | 1.35 | 75.36 |

We achieved a significant performance improvement with the Lithops serverless implementation, reducing the execution time from 14.21 minutes to just 4.87 minutes, which represents a 65% speedup. This improvement is largely due to the dynamic scaling capabilities of Lithops, which allowed us to run many more parallel tasks than the Spark cluster could handle. The average resource usage also increased from 54.56% to 75.36%, indicating that the Lithops implementation was able to utilize resources more efficiently. However, the cost of the Lithops implementation was higher, at $1.35 compared to $0.66 for the Spark cluster, mainly due to the increased number of parallel vCPUs provisioned.

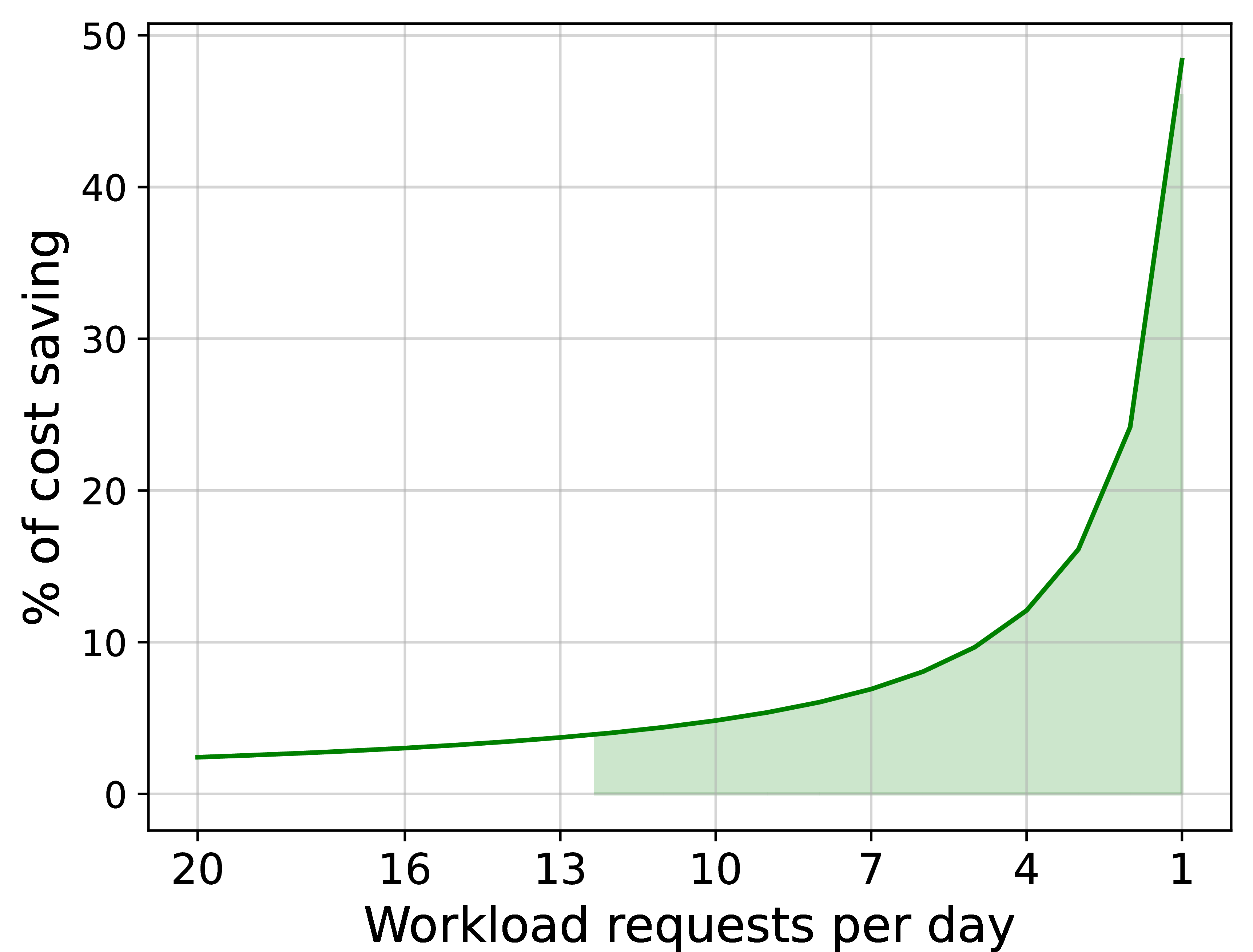

Despite this, the overall performance gain and resource efficiency make the Lithops serverless architecture a compelling choice for sporadic, and bursty workloads like the METASPACE metabolomics pipeline. Provisioning a static cluster for such workloads would have resulted in significant resource underutilization and higher costs in the long term, as the cluster would have been idle most of the time. In contrast, Lithops allows us to provision resources immediately and in real time, as annotation workload requests are submitted. We depict such advantage in Figure 9, where we simulate the monthly savings switching from a static cluster to a Lithops deployment, provisioning resources on demand on a per-workload basis.

Figure 9:Simulated monthly cost savings: ratio of the monthly cost between a static PySpark deployment vs. an on-demand Lithops deployment for varying workload frequencies.

Lithops delivers substantial cost savings at low workload frequencies—achieving nearly a 50% reduction in monthly costs when running a single workload per day. Even as the frequency increases (e.g., up to 20 requests per day), Lithops continues to provide cost benefits over the static approach. It is important to note that this simulation assumes a constant workload size per request; in real-world scenarios like METASPACE, where workload sizes can vary significantly, Lithops’ elasticity would further amplify these savings by dynamically allocating resources to match each workload’s actual requirements.

In terms of usability, some METASPACE applications have been integrated into PyRun to provide a user-friendly interface for running these serverless data pipelines. PyRun hinders the complexity of managing the environment and its dependencies, allowing researchers to focus on their data analysis tasks without worrying about configuration issues. This integration has made it easier for scientists to leverage the power of serverless computing and dynamic partitioning in their research workflows.

6Conclusion¶

Ultimately, harnessing the power and advantages of serverless computing for data analytics in Python has transformed how scientists and developers tackle large-scale data processing. With production-ready tools like Lithops, which enables efficient and scalable execution of functions in the cloud; Dataplug, which simplifies partitioning of complex scientific datasets not originally designed for cloud environments; and PyRun, which streamlines development environment setup, a robust ecosystem has emerged that allows users to focus completely on their code, rather than the underlying infrastructure.

Copyright © 2025 Molina-Giménez et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creators.

- AI/ML

- Artificial Intelligence / Machine Learning

- API

- Application Programming Interface

- AWS

- Amazon Web Services

- COG

- Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFF

- COPC

- Cloud-Optimized Point Cloud

- FaaS

- Function-as-a-Service

- GB/s

- Gigabytes per second

- HTTP

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol

- IDE

- Integrated Development Environment

- imzML

- Imaging Mass Spectrometry Markup Language

- LLM

- Large Language Model

- MS

- Mass Spectrometry

- S3

- Simple Storage Service

- Shvachko, K., Kuang, H., Radia, S., & Chansler, R. (2010). The Hadoop Distributed File System. 2010 IEEE 26th Symposium on Mass Storage Systems and Technologies (MSST), 1–10. 10.1109/MSST.2010.5496972

- Zaharia, M., Xin, R. S., Wendell, P., Das, T., Armbrust, M., Dave, A., Meng, X., Rosen, J., Venkataraman, S., Franklin, M. J., Ghodsi, A., Gonzalez, J., Shenker, S., & Stoica, I. (2016). Apache Spark: a unified engine for big data processing. Commun. ACM, 59(11), 56–65. 10.1145/2934664

- Barcelona-Pons, D., Arjona, A., Garcia Lopez, P., Molina-Giménez, E., & Klymonchuk, S. (2025). Burst Computing Artifact (paper in USENIX ATC’25). Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.15423616

- Jonas, E., Pu, Q., Venkataraman, S., Stoica, I., & Recht, B. (2017). Occupy the cloud: distributed computing for the 99%. Proceedings of the 2017 Symposium on Cloud Computing, 445–451. 10.1145/3127479.3128601

- Sampé, J., Sánchez-Artigas, M., Vernik, G., Yehekzel, I., & García-López, P. (2023). Outsourcing Data Processing Jobs With Lithops. IEEE Transactions on Cloud Computing, 11(1), 1026–1037. 10.1109/TCC.2021.3129000

- Sanfilippo, S., & community, R. (2009). Redis. %5Curl%7Bhttps://redis.io%7D

- Amazon Web Services (AWS). (2025). Amazon ElastiCache: Managed In‑Memory Data Store & Cache. https://aws.amazon.com/elasticache/

- Sánchez-Artigas, M., & Eizaguirre, G. T. (2022). A seer knows best: optimized object storage shuffling for serverless analytics. Proceedings of the 23rd ACM/IFIP International Middleware Conference, 148–160. 10.1145/3528535.3565241

- Arjona, A., García-López, P., & Barcelona-Pons, D. (2024). Dataplug: Unlocking extreme data analytics with on-the-fly dynamic partitioning of unstructured data. 2024 IEEE 24th International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Internet Computing (CCGrid), 567–576. 10.1109/CCGrid59990.2024.00069

- Rocklin, M. (2015). Dask: Parallel Computation with Blocked Algorithms and Task Scheduling. In K. Huff & J. Bergstra (Eds.), Proceedings of the 14th Python in Science Conference (pp. 130–136). 10.25080/Majora-7b98e3ed-013

- Jupyter Development Team. (2025). JupyterLab: A Next-Generation Notebook Interface. https://github.com/jupyterlab/jupyterlab

- Google LLC. (2025). Google Colaboratory. https://colab.research.google.com/

- Alexandrov, T., Ovchnnikova, K., Palmer, A., Kovalev, V., Tarasov, A., Stuart, L., Nigmetzianov, R., & Fay, D. (2019). METASPACE: A community-populated knowledge base of spatial metabolomes in health and disease. 10.1101/539478

- Schramm, T., Hester, Z., Klinkert, I., Jean Pierre, B., Heeren, R., Brunelle, A., Laprévote, O., Desbenoit, N., Robbe, M.-F., Stoeckli, M., Spengler, B., & Römpp, A. (2012). imzML – A Common Data Format for the Flexible Exchange and Processing of Mass Spectrometry Imaging Data. Journal of Proteomics, 75, 5106–5110. 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.07.026